Lewis Fry Richardson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

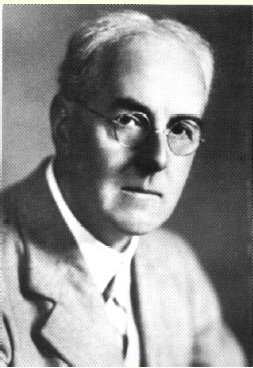

Lewis Fry Richardson

|

|

|---|---|

Lewis Fry Richardson D.Sc., FRS

|

|

| Born | 11 October 1881 Newcastle upon Tyne, England

|

| Died | 30 September 1953 (aged 71) Kilmun, Argyll and Bute, Scotland

|

| Citizenship | United Kingdom |

| Alma mater | Bootham School Durham College of Science King's College, Cambridge |

| Known for | Fractals Conflict modelling Richardson extrapolation |

| Awards | Fellow of the Royal Society |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | mathematician physicist meteorologist psychologist |

| Institutions | National Physical Laboratory National Peat Industries University College Aberystwyth Meteorological Office Paisley Technical College |

| Influences | Karl Pearson G. F. C. Searle J. J. Thomson |

| Influenced | Benoit Mandelbrot |

Lewis Fry Richardson (born October 11, 1881 – died September 30, 1953) was an amazing English scientist. He was a mathematician, physicist, meteorologist (someone who studies weather), and psychologist (someone who studies the mind). He was also a pacifist, meaning he believed in peaceful ways to solve problems, not war.

Richardson was a pioneer in using math to predict the weather. He also used similar math ideas to study why wars happen and how to prevent them. You might also know him for his early work on fractals, which are complex patterns that repeat themselves.

Contents

Early life and education

Lewis Fry Richardson was the youngest of seven children. His family were Quakers, a religious group known for their peaceful beliefs. His father ran a successful business making leather.

When he was 12, Lewis went to a Quaker boarding school called Bootham School in York. There, he developed a strong interest in science and nature. Later, he studied at Durham College of Science and King's College, Cambridge, where he learned about mathematical physics, chemistry, and biology. He even earned a special degree in mathematical psychology when he was 47 years old.

Career journey

Richardson had many different jobs throughout his life, showing his wide range of interests:

- He worked at the National Physical Laboratory twice (1903–1904 and 1907–1909).

- He taught at University College Aberystwyth (1905–1906).

- He was a chemist for National Peat Industries (1906–1907).

- He managed a lab at the Sunbeam Lamp Company (1909–1912).

- He taught at Manchester College of Technology (1912–1913).

- He worked for the Meteorological Office, which is the UK's weather service (1913–1916 and 1919–1920).

- During World War I, he worked with the Friends Ambulance Unit in France, helping injured people (1916–1919).

- He became the head of the Physics Department at Westminster Training College (1920–1929).

- Finally, he was the Principal of Paisley Technical College (1929–1940).

In 1926, he was chosen to be a Fellow of the Royal Society. This is a very high honor for scientists in the UK.

His beliefs and work

Richardson's Quaker beliefs meant he was a strong pacifist. This meant he refused to fight in World War I. Instead, he helped as an ambulance worker. Because of his beliefs, he had to leave his job at the Meteorological Office when it became part of the Air Ministry (which deals with military air forces).

His pacifism also affected his science. He learned that some of his weather research could be used to help design chemical weapons. Because he was against war, he stopped working on that topic and even destroyed some of his notes! He then focused his research on understanding the causes of war.

Weather forecasting ideas

Richardson was very interested in meteorology, the study of weather. He came up with a way to predict weather using complex math equations. This is the method used today, but back then, there were no fast computers to do the calculations.

In 1922, he wrote a book called Weather Prediction by Numerical Process. In it, he imagined a huge "weather factory" where thousands of people would work together to calculate the weather: "Imagine a large hall like a theatre... The walls of this chamber are painted to form a map of the globe... A myriad computers [people who compute] are at work upon the weather... The work of each region is coordinated by an official of higher rank... From the floor of the pit a tall pillar rises... In this sits the man in charge of the whole theatre; he is surrounded by several assistants and messengers. One of his duties is to maintain a uniform speed of progress in all parts of the globe."

This idea was far ahead of its time. When the first modern computer, ENIAC, made its first weather forecast in 1950, Richardson was very excited. It took ENIAC almost a full day to make a 24-hour forecast!

Richardson also studied atmospheric turbulence, which is the swirly, chaotic movement of air. The Richardson number, a special measurement used in turbulence theory, is named after him. He famously described turbulence in a short poem: Big whirls have little whirls that feed on their velocity,

- and little whirls have lesser whirls and so on to viscosity.

Richardson's weather prediction attempt

One of Richardson's most famous efforts was trying to predict the weather for a single day (May 20, 1910) using his math methods. Back then, weather forecasts were mostly made by looking at old weather patterns. Richardson tried to use a math model of the atmosphere and data from 7 AM to calculate the weather six hours later.

His first attempt didn't work well, predicting a huge change in air pressure that didn't happen. However, later studies showed that if he had used some special math techniques to smooth out the data, his forecast would have been quite accurate. This was an amazing achievement, especially since he did all the calculations by hand while working as an ambulance driver in France!

Measuring coastlines and borders

Richardson also looked into why the length of a country's border or coastline seemed to change depending on how it was measured. For example, the border between Spain and Portugal was listed as either 987 km or 1214 km in different books.

This problem is called the "coastline paradox". Imagine you want to measure the coast of Britain. If you use a very long ruler, you'll get one length. But if you use a shorter ruler, you can measure more of the small curves and inlets, making the coastline appear longer. The smaller the ruler, the longer the measured coastline becomes!

Richardson showed that the measured length of coastlines and other natural features keeps getting longer as you use smaller and smaller measuring units. This is known as the Richardson effect.

At the time, his work was mostly ignored. But today, it's seen as a very important step in the study of fractals. Fractals are complex shapes that look similar no matter how much you zoom in. The mathematician Benoît Mandelbrot later used Richardson's ideas when he developed the modern study of fractals. Richardson's work helped lead to the idea of "fractal dimension", which describes how "rough" or complex a shape is.

Iceberg detection patents

After the famous ship Titanic sank in 1912, Richardson came up with an idea to detect icebergs. He registered a patent for using sound waves (like an echo) to find icebergs in the air. A month later, he patented a similar idea for using sound waves in water. This was before sonar (which uses sound to detect objects underwater) was invented!

Personal life

In 1909, Lewis married Dorothy Garnett. They couldn't have their own children, so they adopted two sons and a daughter between 1920 and 1927.

His nephew, Ralph Richardson, became a very famous actor. His great-nephew, Julian Hunt, also became a meteorologist and even led the British Meteorological Office for a few years.

Legacy and recognition

Since 1997, a special award called the Lewis Fry Richardson Medal has been given out by the European Geosciences Union. It honors scientists who have made amazing contributions to understanding complex systems in Earth sciences.

Some of the winners include:

- 2023: Angelo Vulpiani

- 2022: Ulrike Feudel

- 2021: Bérengère Dubrulle

- 2020: Valerio Lucarini

- 2019: Shaun Lovejoy

- 2018: Timothy N. Palmer

- 2017: Edward Ott

- 2016: Peter L. Read

- 2015: Daniel Schertzer

- 2014: Olivier Talagrand

- 2013: Jürgen Kurths

- 2012: Harry Swinney

- 2011: Catherine Nicolis

- 2010: Klaus Fraedrich

- 2009: Stéphan Fauve

- 2008: Akiva Yaglom

- 2007: Ulrich Schumann

- 2006: Roberto Benzi

- 2005: Henk A. Dijkstra

- 2004: Michael Ghil

- 2003: Uriel Frisch

- 2002: Friedrich Hermann Busse

- 2001: Julian Hunt

- 2000: Benoit Mandelbrot

- 1999: Raymond Hide

- 1998: Vladimir Keilis-Borok

Also, since 1959, there has been a research center at Lancaster University called the Richardson Institute. It studies peace and conflict, continuing Lewis Fry Richardson's ideas.

See also

- Anomalous diffusion

- Arms race

- Coastline paradox

- Energy cascade

- War cycles

- Magnetic helicity

- Richardson extrapolation

- Richardson number

- Modified Richardson iteration

- Richards equation

- Multiscale turbulence

- Takebe Kenko

- Frederick W. Lanchester

- List of peace activists

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |