Benoit Mandelbrot facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Benoit Mandelbrot

|

|

|---|---|

Mandelbrot at a TED conference in 2010

|

|

| Born | 20 November 1924 |

| Died | 14 October 2010 (aged 85) Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Nationality |

|

| Alma mater | École Polytechnique California Institute of Technology University of Paris |

| Known for |

|

| Spouse(s) |

Aliette Kagan

(m. 1955–2010; his death) |

| Awards |

2003 Japan Prize 1993 Wolf Prize 1989 Harvey Prize 1986 Franklin Medal 1985 Barnard Medal |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions |

Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

|

| Doctoral advisor | Paul Lévy |

| Doctoral students |

|

| Influences | Johannes Kepler, Paul Lévy, Szolem Mandelbrojt |

| Influenced | Nassim Nicholas Taleb |

Benoit B. Mandelbrot (born November 20, 1924 – died October 14, 2010) was a famous mathematician. He was born in Poland and later became a citizen of France and the United States. He was known as a polymath, meaning he had knowledge in many different subjects.

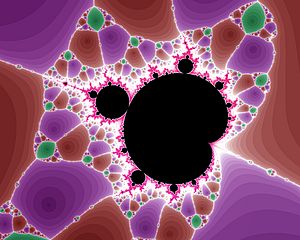

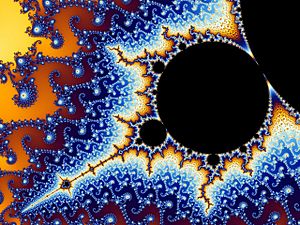

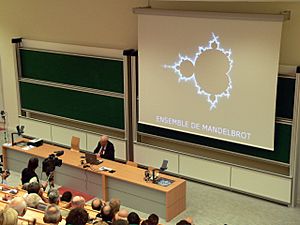

Mandelbrot is most famous for his work on fractal geometry. He even created the word "fractal." He studied the "roughness" and "self-similarity" found in nature. This means he looked at how patterns repeat themselves at different sizes.

In 1936, when he was 11, his family moved from Poland to France. After World War II, he studied mathematics in Paris and the United States. He earned a master's degree in aeronautics (the science of flight).

He spent most of his career working at IBM. There, he used computers to create and show fractal images. This led to his amazing discovery of the Mandelbrot set in 1980. He showed that even things that look messy, like clouds or coastlines, have a hidden order.

Toward the end of his career, he taught at Yale University. He was the oldest professor there to get a permanent teaching position.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Benoit Mandelbrot was born in Warsaw, Poland. His family was Jewish. His father sold clothes, and his mother was a dental surgeon. For his first two years of school, his uncle taught him at home. His uncle didn't like learning by just memorizing things. Benoit spent his time playing chess, reading maps, and learning to observe the world around him.

In 1936, his family moved to France to escape problems in Poland. This move, along with World War II, affected his schooling. His uncle, Szolem Mandelbrojt, who was also a mathematician, helped him. Benoit said that his family moving to France saved their lives.

Mandelbrot went to school in Paris until World War II started. Then his family moved to Tulle, France. A rabbi named David Feuerwerker helped him continue his studies.

In 1944, Mandelbrot went back to Paris. He studied at the École Polytechnique, where he learned from famous mathematicians. From 1947 to 1949, he studied in the United States. He earned a master's degree in aeronautics from the California Institute of Technology. In 1952, he got his PhD in Mathematical Sciences from the University of Paris.

Discovering Fractals

From 1949 to 1958, Mandelbrot worked at a French research center. He also spent a year at the Institute for Advanced Study in the U.S. In 1955, he married Aliette Kagan. They moved to Switzerland and then to the United States in 1958. He joined IBM's research staff in New York. He stayed at IBM for 35 years.

At IBM, Mandelbrot worked on many different problems. He published papers in mathematics, information theory, and economics.

Fractals in Finance

Mandelbrot looked at how financial markets behave. He saw them as "wildly random." He noticed that price changes didn't follow typical patterns. Instead, they had "long range dependence." This means that past events could affect future prices for a long time.

He found that prices, like cotton prices, followed a special type of distribution. This was different from the usual "bell curve" that many random events follow. His early work on this was done before he even created the word "fractal." Later, with better computer data, he used fractal ideas to study how markets work. His research showed that markets have similar properties at different time scales. This supported his idea that markets have a fractal nature.

Creating the Mandelbrot Set

While teaching at Harvard University, Mandelbrot started studying mathematical shapes called Julia sets. These shapes stayed the same even after certain changes. He used computers to draw pictures of these Julia sets. While exploring them, he discovered the famous Mandelbrot set in 1979.

In 1975, Mandelbrot came up with the word fractal. He first wrote about his ideas in a French book. The word "fractal" comes from the Latin word "fractus," meaning broken or shattered.

A computer scientist named Stephen Wolfram said Mandelbrot's book was a "breakthrough." He described fractals as a type of repeating pattern. Smaller and smaller copies of a pattern are nested inside each other. This means the same complex shapes appear no matter how much you zoom in. Think of a fern leaf or Romanesco broccoli. They show this kind of repeating pattern.

Mandelbrot used IBM's new computers to create fractal images. These images looked like amazing, complex art. They reminded people of shapes found in nature and the human body. He saw himself like Johannes Kepler, a scientist who described the orbits of planets.

Mandelbrot didn't feel like he was inventing a completely new idea. He felt he was bringing together old ideas in a new way. Science writer Arthur C. Clarke called the Mandelbrot set "one of the most astonishing discoveries in the entire history of mathematics."

In 1982, Mandelbrot updated his ideas in his book The Fractal Geometry of Nature. This book made fractals popular in math and science. It also convinced people who thought fractals were just computer tricks.

Mandelbrot left IBM in 1987. He then joined the math department at Yale University. He got his first permanent teaching job there in 1999, when he was 75 years old.

Fractals and "Roughness"

Mandelbrot created the first "theory of roughness." He saw "roughness" everywhere in nature. This included the shapes of mountains, coastlines, and river basins. He also saw it in plants, blood vessels, and lungs. Even the way galaxies cluster together showed this roughness. His goal was to find a math formula to measure this "roughness" in natural objects.

In his famous paper from 1967, "How Long Is the Coast of Britain? Statistical Self-Similarity and Fractional Dimension," Mandelbrot talked about self-similar curves. These curves are examples of fractals. He didn't use the word "fractal" yet, but the idea was there. This paper was one of his first important works on fractals.

Mandelbrot believed that fractals were useful for describing many "rough" things in the real world. He said that "real roughness is often fractal and can be measured." Before Mandelbrot, other mathematicians had described some of these shapes. But they were seen as strange and unusual. Mandelbrot brought them together. He showed they were important tools for understanding the non-smooth, "rough" objects in nature.

Fractals are also found in human creations, like music, painting, and architecture. Mandelbrot thought fractals were more natural than the perfectly smooth shapes of traditional Euclidean geometry.

People called Mandelbrot an artist and a visionary. His writing style was easy to understand. He used many pictures to explain his ideas. This made The Fractal Geometry of Nature popular with many people. The book helped spread interest in fractals and chaos theory.

Mandelbrot also used his ideas in cosmology (the study of the universe). In 1974, he offered a new way to explain Olbers' paradox. This paradox asks why the night sky is dark if there are so many stars. Mandelbrot suggested that if stars were arranged in a fractal pattern, the sky could be dark even without the Big Bang theory. His model didn't rule out the Big Bang, but it showed another possibility.

Awards and Honors

Benoit Mandelbrot received many awards for his work.

- In 1993, he won the Wolf Prize for Physics.

- In 2000, he received the Lewis Fry Richardson Prize.

- In 2003, he won the Japan Prize.

- In 2006, he received the Einstein Lectureship.

A small asteroid named 27500 Mandelbrot was named after him. In France, he was made a Chevalier (Knight) of the Legion of Honour in 1990. In 2006, he was promoted to an Officer of the Legion of Honour. He also received over 15 honorary doctorates from universities.

Here is a partial list of his awards:

- 2004 Best Business Book of the Year Award

- AMS Einstein Lectureship

- Barnard Medal

- Caltech Service

- Casimir Funk Natural Sciences Award

- Charles Proteus Steinmetz Medal

- High School Spelling Bee (1940)

- Fellow, American Geophysical Union

- Fellow of the American Statistical Association

- Fellow of the American Physical Society (1987)

- Franklin Medal

- Harvey Prize (1989)

- Honda Prize

- Humboldtpreis

- IBM Fellowship

- Japan Prize (2003)

- John Scott Award

- Légion d'honneur (Legion of Honour)

- Lewis Fry Richardson Medal

- Medaglia della Presidenza della Repubblica Italiana

- Médaille de Vermeil de la Ville de Paris

- Nevada Prize

- Member of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters.

- Member of the American Philosophical Society (2004)

- Science for Art

- Sven Berggren-Priset

- Wacław Sierpiński medal of the Polish Mathematical Society (2005)

- Władysław Orlicz Prize

- Wolf Foundation Prize for Physics (1993)

Death and Legacy

Benoit Mandelbrot passed away on October 14, 2010, at the age of 85. He died from pancreatic cancer in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Many people shared their thoughts after his death. Mathematician Heinz-Otto Peitgen said Mandelbrot was "one of the most important figures of the last fifty years." Chris Anderson, who organizes the TED conferences, called Mandelbrot "an icon who changed how we see the world."

The President of France, Nicolas Sarkozy, said Mandelbrot had "a powerful, original mind." He said Mandelbrot was not afraid to innovate and break old ideas. The Economist newspaper called him the "father of fractal geometry."

Author Nassim Nicholas Taleb said Mandelbrot's book The (Mis)behavior of Markets was "The deepest and most realistic finance book ever published." Mandelbrot's work continues to influence many fields of science and mathematics.

See also

In Spanish: Benoît Mandelbrot para niños

In Spanish: Benoît Mandelbrot para niños

- 1/f noise

- Fractal dimension

- Fractional Brownian motion

- How Long is the Coast of Britain?

- Hurst exponent

- Kurtosis risk

- Lacunarity

- Louis Bachelier

- Mandelbrot Competition

- Multifractal system

- Self-similarity

- Seven states of randomness

- Skewness risk

- Zipf–Mandelbrot law

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |