Limehouse Cut facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Limehouse Cut |

|

|---|---|

Looking North East along the Limehouse Cut

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

| Specifications | |

| Status | Open |

| Navigation authority | Canal and River Trust |

| History | |

| Original owner | Trustees of the Lee Navigation |

| Principal engineer |

|

| Other engineer(s) |

|

| Date of act | 1766 |

| Date of first use | 1769 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Bow Locks |

| End point | Limehouse Basin |

| Connects to | (part of) Lee Navigation |

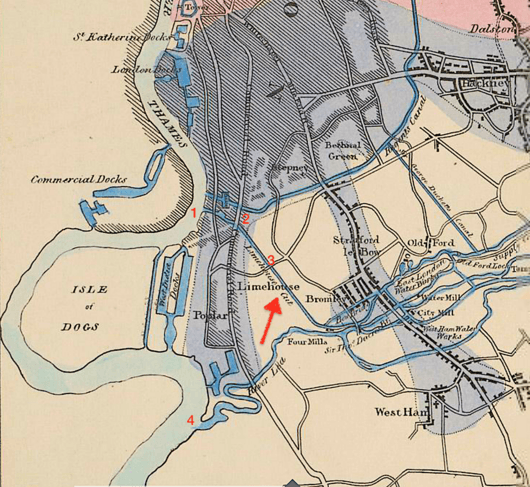

The Limehouse Cut is a wide, straight canal in the East End of London. It connects the lower part of the Lee Navigation to the River Thames. This canal opened on 17 September 1770. It was later made wider for two-way boat traffic by 1777. It is the oldest canal in the London area.

Even though it is short, the Limehouse Cut has a rich history. It used to flow directly into the Thames. Since 1968, it connects to the Thames through Limehouse Basin. The canal is about 2.2 kilometers (1.375 miles) long. It starts with a wide curve from Bow Locks, where the Lee Navigation meets Bow Creek. Then, it goes straight southwest through the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. Finally, it makes a short turn to connect to Limehouse Basin.

Contents

- How the Limehouse Cut Began

- Victorian Era Changes

- 20th Century Changes

- Social and Industrial History

- The Limehouse Cut Today

- See Also

How the Limehouse Cut Began

Why Was the Canal Needed?

Even in the time of Queen Elizabeth I, there was a busy trade on the River Lea. Boats carried goods between towns on the river and the City of London. However, boatmen had to wait for the tides. They also had to row all the way around the Isle of Dogs. This made journeys long and difficult.

For example, in 1588, many barges carried wheat and malt from Hertfordshire to London. They would load up on Saturday and reach Bow Lock by Monday. Then, they waited for the tide to turn to open the gates. The journey to London took about four hours. The return trip with coal or salt also depended on the tides. By 1739, about 25,000 tons of grain and other goods moved on the River Lea. When the Limehouse Cut was built, this traffic grew to 36,000 tons. This was about a quarter of London's grain supply!

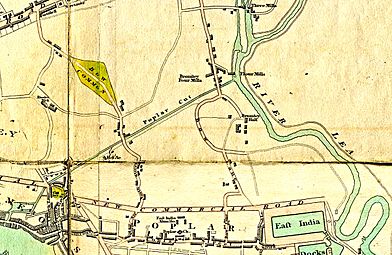

Planning the Canal's Route

The idea for the Limehouse Cut came from the Lee Navigation Improvement Act of 1766. Engineer John Smeaton saw that new cuts were needed. His assistant, Thomas Yeoman, also had the same idea. Thomas Yeoman was chosen to survey the River Lee. One of his first jobs was to find a route for the Limehouse Cut.

The canal would be a shortcut from the Lee Navigation at Bromley-by-Bow to the River Thames. It would avoid the twisty parts of the River Lea at Bow Creek. It also meant boats would not have to wait for the tide to go around the Isle of Dogs. In 1767, the trustees agreed to Yeoman's route. It would end at Dingley's Wharf in Limehouse.

Building the Canal and Locks

The work to dig the canal was split into two parts. Charles Dingley, who owned a wharf and was a trustee, got the southern part. Jeremiah Ilsley got the northern part up to Bow Locks. Building Bromley Lock was a separate job. Mr. Cooper, a millwright, won this contract.

The lock leading to the Thames was designed by Mr. Collard. It was estimated to cost £1,547. But Collard miscalculated the length, so the cost went up to £1,696.

Opening and Making it Wider

By 1769, some boats were already using parts of the canal. The official opening was planned for July 2, 1770. However, 60 feet of brickwork fell into the canal. This delayed the opening until September 17. More problems happened in December when a bridge collapsed. But once these early issues were fixed, more and more boats used the canal.

At first, the canal was only wide enough for one barge. In 1772, a passing place was added. But by 1773, the company decided to make the whole canal wider. This way, barges could pass each other anywhere. Jeremiah Ilsley got the contract for this work in 1776. The wider canal was ready on September 1, 1777, and cost £975.

Later Widening of the Canal

The Limehouse Cut was later made even wider, from 55 feet to its current 75 feet. It's not clear exactly when this happened. Some think it was during changes made by Nathaniel Beardmore in the 1850s. However, this seems unlikely. It might have happened when the Commercial Road was built. An old picture from 1809 seems to show digging work next to the canal.

Water Flow Challenges

Even though the Limehouse Cut saved time, it had problems with water. It was a tidal canal, meaning its water level changed with the tides. It could also get shallow.

Near the northern end, there was a conflict with a place called Four Mills. These were five water wheels that used the tide for power. Nathaniel Beardmore, the engineer for the Lee trustees, explained the problem. The mills would draw water very fast after high tide. This often left the canal too shallow for boats. The Limehouse Cut depended on tidal water. It was not navigable during "neap tides" (when tides are weakest). This meant boats sometimes couldn't get to the Thames for days.

The canal had no locks except at its ends, even though the land dropped 17.5 feet. The shallowest point was a big issue. Beardmore said the Limehouse Cut always had trouble with water levels and shifting sand. No major improvements were made until the Victorian era.

The First Limehouse Basin

Near its Limehouse end, the canal was made wider to form a basin. This basin had an island in the middle. This was the first Limehouse basin. It was built 25 years before the more famous Regent's Canal Dock. The reason for this basin and island is explained later.

Victorian Era Changes

Competition from Railways

By 1843, a railway line was built from Stratford to Hertford. This railway, the Eastern Counties Railway, ran next to the River Lee. It started to take away business from the canal.

Buying Out the Four Mills

To improve the canal, the Lee Navigation trustees bought the Four Mills in 1847. They gradually stopped the mills from using water power. This was an important first step.

James Rendel's Improvement Plan

In 1849, engineer James Rendel was asked to create a plan to fix the canal system. He said that to compete with railways, the canal needed to be better. It had to be able to handle the largest barges used on the Thames. He suggested rebuilding Bromley Lock and making the Limehouse Cut deeper. He also proposed building a new lock into the Thames.

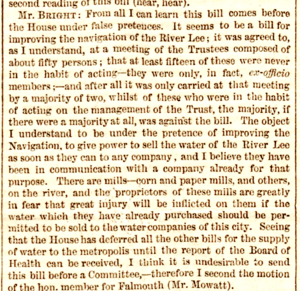

Funding and Political Challenges

The Limehouse Cut's engineering plans faced political problems. The River Lee had many uses. It was a route for traders, supplied London with drinking water, powered mills, and was used as a sewer. There was no single group managing all these different needs.

The River Lee's navigation was managed by a board of unpaid trustees. The most powerful was James Gascoyne-Cecil, 2nd Marquess of Salisbury. He became chairman in 1851. Rendel's plan was estimated to cost £230,000. This is about £30 million in today's money. The Trust's income was small. However, the clerk, John Marchant, had an idea. They would borrow money and pay it back by selling more water to London's water companies.

The plan was controversial. Many river traders opposed it. They felt the benefits were not worth the large debt the Trust would take on. They worried about higher tolls. Despite this, the plan was approved by a small margin of votes. A Bill was presented to Parliament. Even with opposition from politician John Bright, it became law in 1850.

The worries of the traders proved right. The water companies were interested in buying water, but they didn't agree on a price. They soon gained the upper hand. The New River Company found another water source. Then, they and the East London Waterworks got their own laws passed to get water from the River Lee. The Trust faced money problems. In the end, the water companies got most of the River Lee's water for much less money.

This meant the Trust had a large debt with no clear way to pay it back. They increased tolls, but still ran out of money. Sacrifices had to be made, especially for the Limehouse Cut.

Nathaniel Beardmore's Work

Rendel's plans were put into action by his former student, Nathaniel Beardmore. The first part of the work was supposed to be on the tidal section, including the Limehouse Cut. However, funds ran out in 1853, and some plans were cut short. When more money became available in 1855, it had to be used for other parts of the Lee.

Some changes were made before the money ran out. The water level in Limehouse Cut was raised. The canal under the Commercial Road bridge was made wider and given a towpath. This allowed larger barges to use the canal:

| Barge Size (max) | With old Lee Navigation | With improved Lee Navigation |

|---|---|---|

| Draught (how deep it sits in water) | 4 feet | 6 feet |

| Length | 85 feet | 110 feet |

| Beam (width) | 13 feet | 19 feet (through Regent's Canal outlet) |

These improvements were said to increase the amount of goods carried on the Lee Navigation by 25%. This happened despite competition from the Eastern Counties Railway.

Temporary Link to Regent's Canal

The old lock to the Thames was falling apart. In 1852, Beardmore reported that the Limehouse Lock was bulging. The lock keeper's house also had to be pulled down.

Around this time, the Lee trustees agreed to sell the southern part of the Limehouse Cut to the Regent's Canal Company. Since it was public property, Parliament had to approve it. The nearby Regent's Canal Dock was already busy. The company wanted to make it bigger, taking over the Limehouse Cut's lock and basin.

While this was being decided, a temporary link was dug in early 1854. This connected the Limehouse Cut to the Regent's Canal Dock. This gave boats another way to reach the Thames. Work south of Commercial Road was overseen by both Beardmore and the Regent Canal's engineer.

The new route could get crowded. It was not popular with boatmen. They did not like the idea of being under Regent's Canal rules. They organized meetings and fought the proposal in Parliament. They won, and the Regent's Canal Company had to settle for a smaller dock expansion. In May 1864, the temporary link was filled in.

Beardmore then replaced the old timber Limehouse Lock. He built a new, wider lock with arched supports to stop the walls from bulging.

Britannia Bridge and Lock

Britannia Bridge is where the Commercial Road crosses the Cut. It was named after the Britannia Tavern, a pub that was there from around 1770 to 1911. The original bridge was too small for the canal and blocked the towpath.

When the Limehouse Cut was connected to the Regent's Canal Dock, a water problem arose. The Limehouse Cut was tidal, but the Regent's Canal was not. Water might flow from one to the other at the wrong times. To control this, a new lock was built at Britannia Bridge. It had gates pointing in both directions. Horses could now pass underneath on the new towpath.

These lock gates were rarely used and were later removed.

The New Bromley Lock

Bromley Lock was completely rebuilt in a slightly different spot. Beardmore explained that the old lock and nearby parts of the canal were very damaged. The canal section near the lock often slipped because of the ground. This made the canal useless for days during neap tides.

So, the new work included rebuilding Bromley Lock. They also deepened, widened, and walled the nearby canal section. The new lock was 137 feet long and 22 feet wide.

In 1888, Joe Child, one of Beardmore's successors, wrote that the locks were filled with mud and rubbish. This caused leaks. Bromley Lock was eventually removed. According to a historian, one gate can still be seen today.

20th Century Changes

Bow Locks were originally partly tidal. High spring tides would flow over them, changing the water level in the Limehouse Cut. In 2000, they were updated. A flood wall and extra flood gates were added. This allowed the lock to be used at all tide levels and kept the canal's water level steady.

After British Waterways took over the canal in 1948, a vertical gate was put on the north side of Britannia Bridge. This was removed in the 1990s.

New Link to Limehouse Basin

By the 1960s, the lock connecting the canal to the Thames needed to be replaced. It had been rebuilt in 1865. Its design included huge timber beams to stop the walls from bulging. These were later replaced with a steel frame. Getting to the lock from the canal and the Thames was tricky. The gates were operated by winches and chains because there wasn't enough space for balance beams.

At that time, the canal was very busy with commercial traffic. Building a new lock would cause major disruptions. So, the solution was to reconnect to the Regent's Canal Dock. The old route from the 1860s couldn't be used because buildings now covered it. So, a new section of canal, about 60 meters (200 feet) long, was built. This new link opened on April 1, 1968. The old lock was then filled in. One of its winches was saved and is now on display at Hampstead Lock.

Social and Industrial History

The Island in the Cut and its Mills

An old map from 1795 shows that part of the canal near Limehouse was widened into a large basin. It had an island in the middle marked "Timber Yd" (Timber Yard). This was the first basin in Limehouse. It was built 25 years before the more famous Regent's Canal dock.

Charles Dingley's Sawmill

Old maps show the basin and island. Nearby streets were named 'Island Row' and 'Mill Place'. These streets still exist, but the "Island" and "Mill" are mostly forgotten. They started with Charles Dingley, a businessman who built the southern end of the Limehouse Cut.

At that time, wooden planks were expensive because they were cut by hand. There was also opposition to sawmills in England. Dingley, a big timber merchant, decided to build a wind-powered sawmill. He bought land near the planned canal, perhaps hoping to use it for his mill. It was the only sawmill in England and did very well.

However, on May 10, 1768, a crowd of 500 men, including hand-sawyers, attacked his sawmill. They destroyed the machines. This event led Parliament to pass a law in 1769 making it a serious crime to damage mills. Dingley repaired his mill by 1769. The island and basin were likely built to protect the repaired sawmill.

The Island Lead Mills

The sawmill was no longer used by 1806. But by 1817, a lead mill was built on the island. It was called The Island Lead Mills. This business thrived into the 20th century. It even had one of the first telephones in the East End of London. Its barges used the canal. The company closed in 1982.

By 1868, the growing Regent's Canal Dock had taken over parts of the Island. More sections were filled in later. Still, you can find traces of it near Victory Place, Limehouse, which is built on the site.

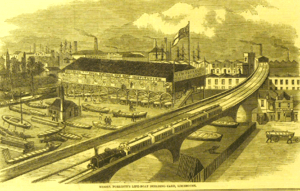

Boatbuilding Along the Cut

Across the Cut from the Island was the boatyard of T & W Forrestt. They built boats for the Royal National Lifeboat Institution. The company built self-righting lifeboats. They tested these boats in the waters of the Limehouse Cut. These boats reportedly saved over 12,000 lives.

Forrestt's yard was called Norway Yard, a name still used in Norway Place. An old picture shows the boatyard after a big fire in 1858. In the foreground is the London and Blackwall Railway. The canal is visible on the left. Across the canal is the Island with the Island Lead Mills.

Stinkhouse Bridge

Bow Common Lane met the Cut at Stinkhouse Bridge. This name was even used in official documents. The name first appeared on a map in 1819.

This area was originally desolate. Chemical factories moved there because they could pollute freely. This caused a terrible smell, giving the bridge its name. Another cause was waste from the Black Ditch, an old sewer. It overflowed in stormy weather. The smell was so bad that people complained they couldn't sleep. Factories dumping waste into the Cut were thought to be the main cause.

Over time, Stinkhouse Bridge became the center of "the largest chemical and flammable factories in London." The area was a fire risk. In 1866, a huge fire broke out. It was so big that all London's firefighters knew where to go just by seeing the light in the sky. Many people jumped into the Cut to escape the flames.

About 200 yards up the Cut was the RNLI's (Royal National Lifeboat Institution) storeyard. Lifeboats were kept there and tested before being put into service. The tests involved sinking the boats in the Cut to check their self-righting ability.

The bridge was rebuilt in 1929. It remained a well-known East End place name even after the smell was gone.

Bathing in the Canal

In 1833, the Limehouse Cut was a popular place for bathing. Local authorities tried to ban it due to concerns about public decency.

The Burdett Road Bridge Area

In 1819, the Cut ran through open countryside from Bromley lock to Britannia Bridge. The only way to cross it was at Stinkhouse Bridge. To the northwest was the Patent Cable Works, where strong ship cables were made. Later, this area was built up. The Cable Works closed, and in 1858, its path was used to build the "Victoria Park Approach Road," soon renamed Burdett Road. A new bridge had to be built over the Cut. Parliament required the bridge to have enough space for barge traffic.

Dod Street and Early Socialism

Dod Street, near Burdett Road Bridge, was built by 1861. Its factories overlooked the Cut. It became known for Sunday political meetings. Socialists like John Burns, Eleanor Marx, and George Bernard Shaw spoke there.

The "Dod Street Trick"

Dod Street gave rise to the phrase "the Dod Street trick" in socialist politics. The police tried to stop these meetings by arresting people for blocking the road. But there was no traffic on this street of factories on a Sunday. So, people felt the police were denying freedom of speech.

The "Dod Street trick" was a way to fight this. Bernard Shaw described it: Find a dozen people willing to be arrested each week for speaking. After a month or two, the repeated arrests, crowds, and newspaper stories would create enough public support. This would force the government to let the meetings continue. This is what happened. Huge crowds gathered, and the police eventually left them alone.

The image titled The law blacks William Morris' boots is a political cartoon. It makes fun of how justice was different for different classes. Working-class protesters were punished, but William Morris, a gentleman, only got a warning.

The cartoon Dod Street Demonstrations shows the area in the late Victorian era. The arrow points towards Limehouse Cut.

On the left, 1 is a rubber factory that made capes for the police and oilskins for the navy.

The last building on the left, 2, is the "Silver Tavern" pub. It was a meeting place for the East End Football Association.

In the distance, 3 is St Anne's Limehouse Church. At the end of the street, a tram 4 has just crossed the Bridge.

The last building on the right, 5, was a warehouse that became the Outcasts' Haven.

Innovative Factories

Most of the north side of Dod Street was taken up by the H. Herrmann factory. It backed onto the Limehouse Cut. Opened in 1877 by Henry Herrmann from America, it made hardwood furniture. It was the first factory in England to do this almost entirely by machine. Its huge stock of timber could be easily brought in by water.

The factory burned down in a massive fire in 1887. Herrmann rebuilt it and added one of the world's first electric traveling cranes. Since there was no electricity supply in London, he generated his own and lit the factory with electricity.

The Fire Brigade continued to use floating fire engines on the Cut until at least 1929.

The Outcasts' Haven

In a disused warehouse at 1A Dod Street was the Outcasts' Haven. It was a place for homeless children. According to Charles Dickens Jr., any child up to 16, without parents or friends, could be admitted for free. They would get a bath, warm clothes, food, and a bed. Police officers would send homeless children there.

However, an investigation by the journal Truth claimed it was a charity scam. It was run by Walter Austin and Frances Napton. They put on events, sent out emotional appeals, and collected large donations. But they didn't keep proper records. While some money went to children, the owners lived very well.

Victorian Recycling Efforts

East End refuse collectors, called "dustmen," took household waste to two yards on the Limehouse Cut. There, old men, women, and boys sorted it by hand. Ash and breeze (small coal pieces) were sent by barge to Kent to make bricks. Rags, bones, and metal were sold to dealers. Old tin was sold to trunk-makers. Old bricks and oyster shells went to builders. Old boots were sold to dye makers. Any money or jewelry found was kept.

The Copenhagen Wharf recycling facility can be seen in an 1886 photograph. This scene is a few yards west of Burdett Road bridge. In the center is Hirsch's Copenhagen Oil Mills, where seeds were crushed for oil.

Slum Areas (Rookeries)

A "rookery" was a slum area where residents often resisted law enforcement.

St Anne's Street Rookery

Across Burdett Road was St Anne's Rookery. It was described as a "vile quarter" between Limehouse Church and Limehouse Cut. On Charles Booth's poverty maps, it was marked black, meaning "Lowest class. Vicious, semi-criminal." It was one of the few slums next to the Cut, as land there was usually too valuable for housing.

This area was known for crime and often appeared in newspaper reports. Law enforcement could be dangerous there.

The Fenian Barracks

Even more dangerous to police was the area near Stinkhouse Bridge. It was bordered by Limehouse Cut to the south and centered on Furze Street. Police informants called it the Fenian Barracks. They said it "sent more police to hospital than any other block in London." Only Irish people were tolerated to settle there.

George H. Duckworth, a researcher, wrote that the Barracks was one of the worst districts in London. In 1929, researchers found that while poor areas in East London were less common, the Fenian Barracks area was still a place of deep poverty.

Caird & Rayner Factory

At 777 Commercial Road, opposite Limehouse Church, is an abandoned building that backed onto the Limehouse Cut. It has a faded sign that says V.I.P. Garage. Originally, it was a ship chandler's (a supplier of ship equipment) from 1869. It has a well-preserved sail loft. Later, it became the workshop and offices of Caird & Rayner.

This company specialized in machines that remove salt from water. This was very important for ship boilers and for providing drinking water on long sea voyages. Their patented machines were used on battleships, liners, and even the Czar's yacht. A sample of their equipment is in the Science Museum. Water from the Cut was used to test the equipment. The company moved in 1972.

In 2000, the building was given special protection for its history and architecture. Its engineering workshop is a very early example of a fully steel building frame. It is probably the only one left in London.

National Politics and the Limehouse Declaration

On January 25, 1981, a group of politicians known as the Gang of Four stood on the bridge over the former Limehouse Lock. There, they announced the Limehouse Declaration. This was a key moment in the formation of the Social Democratic Party (SDP).

Other Names for the Cut

The Limehouse Cut has been known by other names over time:

| NAME(S) | SOURCE | DATE |

|---|---|---|

| "River Lea" (even where entering Thames at Limehouse) | John Cary's New and Accurate Plan of London and Westminster | 1795 |

| "Limehouse Cut or Bromley Canal" | John Fairburn's Map of London and Westminster | 1802 |

| "Poplar Cut" (not to be confused with Poplar Gut) | Edward Mogg's London in Miniature | 1809 |

| "Lea Cut" (in Bromley); "Limehouse Cut" (in Limehouse) | G. F. Cruchley's New Plan of London | 1827 |

| "Bromley Canal or Lea Cut" | Kelly's Post Office Directory Map | 1857 |

| "Lea Cut" (east of Bow Common Lane); "Limehouse Cut" (to west) | Cross's New Plan of London | 1861 |

The Limehouse Cut Today

Today, the canal is mostly used for fun. People enjoy boating on the water and walking or cycling on the towpaths beside it. The Regent's Canal, the Hertford Union Canal, the Lee Navigation, and the Limehouse Cut form a 5.5-mile (8.8 km) loop. This loop is great for walking or cycling. The scenic towpaths cross over roads and railways, offering unique views.

Walking along the Limehouse Cut was once difficult near the Blackwall Tunnel approach road. But this was made easier in July 2003 with an innovative floating towpath. It uses 60 floating platforms to create a 240-meter (260 yd) walkway with green glowing edges.

The Cut is part of the Lee Navigation and is managed by the Canal & River Trust. It was built for sailing barges. It can fit boats up to 88 feet (26.8 m) long and 19 feet (5.8 m) wide. The height limit for boats is 6.75 feet (2.06 m). The lock from Limehouse Basin to the Thames was once for large ships but is now smaller.

The area around Limehouse Basin has been redeveloped. However, the row of houses overlooking the old lock, built in 1883, have been kept and restored. The site of the old lock is now a shallow pool. At the end of the London 2012 Olympic torch relay, David Beckham arrived with the Olympic torch on a speedboat through the Limehouse Cut. He was on his way to the Olympic opening ceremony.

Interesting Places Along the Cut

| Point | Coordinates (Links to map resources) |

OS Grid Ref | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bow Locks | 51°31′24″N 0°00′29″W / 51.5233°N 0.0081°W | TQ382823 | northern end of cut |

| A12 Blackwall Tunnel Approach | 51°31′18″N 0°00′37″W / 51.5216°N 0.0104°W | TQ381821 | Floating towpath under bridge |

| Docklands Light Railway bridge | 51°31′09″N 0°00′55″W / 51.5192°N 0.0154°W | TQ377818 | |

| A13 road bridge | 51°30′45″N 0°01′54″W / 51.5124°N 0.0318°W | TQ366811 | |

| Limehouse Basin | 51°30′40″N 0°02′10″W / 51.5111°N 0.0362°W | TQ363809 | southern end of cut |

See Also

- Spratt's Complex, a nearby building that used to be a warehouse.

- Canals of the United Kingdom

- History of the British canal system

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |