Lloyd L. Gaines facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

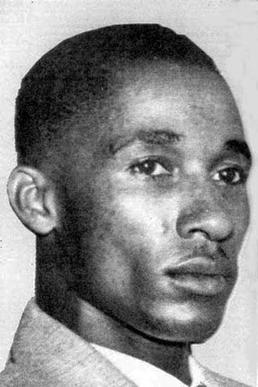

Lloyd L. Gaines

|

|

|---|---|

Lloyd Gaines

|

|

| Born |

Lloyd Lionel Gaines

1911 Water Valley, Mississippi, U.S.

|

| Disappeared | March 19, 1939 (aged 27 or 28) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Status | Missing for 86 years, 11 months and 6 days |

| Education | History (BA) Economics (MA) |

| Alma mater | Lincoln University University of Michigan |

Lloyd Lionel Gaines (born 1911 – disappeared March 19, 1939) was a brave young man who played a key role in the early civil rights movement in the United States. He was the main person, called the plaintiff, in a very important court case known as Gaines v. Canada in 1938.

Lloyd Gaines wanted to study law at the University of Missouri School of Law. But he was Black, and the university only allowed white students. They offered to pay for him to go to law school in another state, but he refused. He believed he had a right to study in his home state. So, he decided to sue.

The highest court in the country, the U.S. Supreme Court, agreed with him. They ruled that if Missouri offered a law school for white students, it had to offer an equal one for Black students within the state. This ruling was a big step in challenging the idea of "separate but equal" schools, which often meant "separate but not equal."

After the ruling, Missouri decided to open a new law school for Black students instead of letting Gaines into the existing one. But before classes started, Lloyd Gaines disappeared in Chicago and was never seen again. His disappearance remains a mystery, but his case helped pave the way for future civil rights victories.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Lloyd Gaines was born in 1911 in Water Valley, Mississippi. When he was 15, his father died, and he moved with his mother and siblings to St. Louis, Missouri. This was part of a big movement called the Great Migration, where many Black families moved from the rural South to cities in the North.

Lloyd was a very good student. He was the top student, or valedictorian, at Vashon High School. He won a scholarship for $250, which helped him go to college.

He attended Lincoln University, a historically black college in Jefferson City, Missouri. This was the state's college for Black students at the time. He graduated with honors, earning a bachelor's degree in history. To help pay for college, he sold magazines. He was also elected president of his senior class and joined the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity.

Applying for Law School

After graduating in 1935, during the Great Depression, Lloyd Gaines tried to find work as a teacher but couldn't. Around this time, a lawyer named Charles Hamilton Houston from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was looking for someone to challenge Missouri's Jim Crow laws. These laws kept Black students out of the University of Missouri.

In June 1935, Gaines asked for an application from the University of Missouri Law School. He was encouraged by his professor, Lorenzo Greene, who was a civil rights activist. When the university registrar, Sy Woodson Canada, received Gaines's application, he didn't realize Gaines was Black. But when he saw Gaines's transcript from Lincoln University, he understood. He didn't act on the application, even though Gaines was qualified.

Canada then sent Gaines a telegram, asking him to meet to discuss "further advice" and "possible arrangement." Gaines wrote to the university president, Frederick Middlebush, asking to be admitted. Middlebush never replied.

The Lawsuit Begins

Missouri had a policy to pay for Black students to attend law school in other states. This was supposed to be a temporary solution until enough Black students wanted to study law in Missouri to build a separate school for them.

In January 1936, Gaines and his lawyers filed a lawsuit. They asked the court to order the university to consider Gaines's application. The university formally denied Gaines's admission. They said that separating students by race was the state's policy. They also argued that Gaines could go to law school outside Missouri at the state's expense.

Since Gaines's application was formally denied, his lawyers filed a new lawsuit. This time, they argued that denying him admission based on race violated his Fourteenth Amendment rights. This amendment guarantees equal protection under the law.

Gaines and his lawyers argued that studying law out of state would be a disadvantage. Students would miss out on learning about Missouri's specific laws and making connections in the state's courts.

The NAACP's goal was not to completely overturn the "separate but equal" rule from the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson case. Instead, they wanted to make states truly provide "equal" facilities. They focused on graduate and professional schools because there were fewer of them, and they were controlled by the state. The NAACP hoped that states would find it too expensive to build separate, equal schools for a small number of Black students. This might lead them to allow Black students into existing white schools instead.

The Trial in Missouri

In July 1936, Gaines, Houston, and Redmond went to Columbia, Missouri, for the trial at the Boone County Courthouse. It was a very hot summer. Many people came to watch, including university students and reporters. Some local Black residents also attended, even though there had been past violence that made many fearful. The courtroom was not segregated, so Black and white people sat together.

Houston argued that Gaines's exclusion based on race was against his constitutional rights. The state's lawyer, William Hogsett, agreed that Gaines was a good student and deserved a legal education. But he said that racial segregation was the state's policy, and Gaines could not attend the University of Missouri.

Gaines himself testified. He said he wanted to attend Missouri's law school because it was good and closer to his home in St. Louis. He also explained that he needed to learn about Missouri law to practice in the state.

The judge ruled in favor of the state. Gaines then appealed to the Missouri Supreme Court.

Appeals to Higher Courts

Missouri Supreme Court's Decision

The Missouri Supreme Court heard the arguments. Two months later, they upheld the lower court's decision. Justice William Francis Frank wrote that even though the state constitution didn't specifically mention higher education, the legislature could still separate races in schools. He said that "equality and not identity of school advantages is what the law guarantees."

Frank also said that Gaines's education out of state would be equal. He noted that some out-of-state schools were closer to St. Louis than Columbia. He also said that Missouri would pay for Gaines's living expenses if he went out of state, which he would have to pay himself if he went to Missouri.

U.S. Supreme Court's Big Decision

Houston and Redmond then took the case to the U.S. Supreme Court. The case was argued in November 1938. Houston argued that paying for Gaines to go to school out of state could not guarantee him an equal legal education.

A month later, the Supreme Court ruled 6-2 in Gaines's favor. Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes wrote the main opinion. He said that Missouri had created a privilege for white law students that it denied to Black students because of their race. He stated that the state had to provide equal opportunities within the state. Paying for tuition in another state did not make up for this unfairness.

This ruling was very important. It meant that any academic program a state offered to white students had to have an equal program available to Black students. The Gaines case helped set the stage for the Supreme Court's famous 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education. That case said that separate public schools were never truly equal and ordered them to be desegregated, overturning the "separate but equal" rule.

Even after this victory, Gaines's legal fight wasn't over. The Supreme Court sent the case back to the Missouri Supreme Court for a new hearing. While waiting, Gaines traveled and gave speeches to NAACP groups. He also looked for work.

The Missouri legislature quickly approved money to turn an old beauty school in St. Louis into the new Lincoln University School of Law. The NAACP planned to challenge this new school, believing it would not be equal to the University of Missouri's law school.

The Mysterious Disappearance

Lloyd Gaines was looking for work while waiting for the new law school to open. It was hard to find a good job because of the Great Depression and segregation. He worked at a gas station for a short time. He also gave speeches to local NAACP groups, saying he was ready to enroll at the University of Missouri. But he still had to borrow money from his brother for daily expenses.

He quit the gas station job after finding out the owner was selling low-quality fuel as high-quality. He then traveled to Kansas City and Chicago, looking for work and visiting friends.

In private, Gaines started to feel unsure about continuing the fight. His mother later said he decided not to go to the University of Missouri because it was "too dangerous." A friend recalled Gaines saying, "If I don't go, I will have at least made it possible for some other boy or girl to go."

In his last letter to his mother, dated March 3, 1939, Gaines wrote about feeling alone in his struggle. He said, "Sometimes I wish I were just a plain, ordinary man whose name no one recognized." He also told her not to worry if he didn't write for a while.

Gaines was staying with friends from his Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity in Chicago. On the evening of March 19, 1939, he told the house attendant he was going out to buy stamps. It was cold and wet outside. Lloyd Gaines never returned. No one ever reported seeing him again.

What Happened Next

Lloyd Gaines left a duffel bag of clothes at the fraternity house. Since he often left without telling anyone, his friends and family didn't immediately worry. No one reported him missing to the police.

Several months later, in August, his lawyers, Houston and Redmond, couldn't find him for the rehearing of his case at the Missouri Supreme Court. The new Lincoln University School of Law opened in September, but Gaines wasn't there. Since only Gaines had the right to pursue the case, it couldn't continue without him.

By late 1939, the NAACP started a big search for Gaines. There were rumors he had been killed or paid to disappear and was living in Mexico City or teaching in New York. His photo was published in newspapers, asking for information. But no good leads came in.

Houston and Redmond never publicly said they believed Gaines had been harmed. Some think they believed Gaines, who had grown tired of the lawsuit, had simply left on purpose. In January 1940, the state of Missouri asked the court to dismiss the case because Gaines was absent. His lawyers did not object, and the case was closed.

Investigations into His Disappearance

No police agency formally investigated Gaines's disappearance at the time. Many Black Americans did not trust the police. J. Edgar Hoover, the head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), said in 1940 that he didn't think the case was under the FBI's control.

Decades later, the FBI agreed to look into Gaines's case as one of many unsolved missing persons cases from the civil rights era.

Ebony Magazine's Look

In 1951, Ebony magazine reporter Edward T. Clayton investigated Gaines's disappearance. He interviewed family members and fraternity brothers. Clayton found that Gaines had become very disappointed with his role as an activist.

Gaines's mother said he had decided not to enroll at the University of Missouri because it was "too dangerous." She said he sent her a final postcard saying, "Goodbye. If you don't hear from me anymore you know I'll be all right." His family has never had him legally declared dead.

Gaines's brother, George, said Lloyd owed him money when he disappeared. He felt the NAACP had used his brother without giving him enough support. George shared Lloyd's last letter, where he wished he was just an ordinary person.

The Riverfront Times Revisits the Case

In 2007, The Riverfront Times newspaper in St. Louis looked at the case again. By then, Gaines had received honors after his disappearance. The FBI had taken on the case. Most people who knew Gaines were no longer alive.

A librarian named Sid Reedy told the newspaper that Lorenzo Greene, Gaines's mentor, claimed to have spoken to Lloyd Gaines by phone in Mexico City in the late 1940s. Greene said Gaines had "grown tired of the fight" and was doing well financially. Greene's son confirmed his father told him about the calls. But Greene didn't report it to the FBI because he didn't trust them.

Some of Gaines's relatives found it hard to believe he would just leave his family. His great-niece, Tracy Berry, who became a federal prosecutor, said, "If he wanted to walk away, there are easier ways to do it than to sever ties from the entire family."

Legacy and Honors

Even though his family never had him legally declared dead, they put up a monument for Lloyd Gaines in a Missouri cemetery in 1999. His great-niece, Tracy Berry, said he "instilled the legacy of education in our family."

In 1939, an African-American newspaper, the Louisville Defender, wrote that Gaines's fate should not stop the fight for equal rights in education.

Thurgood Marshall, who later became the first African-American Supreme Court Justice, called the Gaines case "one of our greatest legal victories." He also said he felt the "pain of having so many people spend so much time and money on him, just to have him disappear."

The Gaines ruling made it hard for states to keep schools separate without also making them truly equal. It meant that:

- Every person had a right to equal education, no matter how few others wanted it.

- States could not send students out of state to meet the "separate but equal" rule.

- The promise of future equality did not make current discrimination okay.

Without Gaines, the NAACP couldn't continue the next part of their plan in the Missouri Supreme Court. This was a setback for their efforts. The NAACP also ran out of money after spending a lot on the case.

The Lincoln University School of Law, which was created because of the case, closed in the mid-1950s because it didn't have enough students.

However, the Gaines case was a crucial step. After World War II, the NAACP found more students to challenge segregation in graduate schools. Finally, in 1954, the Brown v. Board of Education case overturned "separate but equal" and ordered schools to desegregate. The University of Missouri School of Law admitted its first African-American student in 1951.

Honors at the University of Missouri

The University of Missouri, especially its law school, began to honor Lloyd Gaines in the late 1990s, even though he was never admitted.

- In 1995, they created a scholarship in his name.

- In 2001, the school's African-American center was named after Gaines and another Black student who challenged the school's color barrier.

- A portrait of Gaines hangs in the law school building.

- In 2006, the law school gave Gaines an honorary degree in law.

- The state's highest court and state bar association also gave him an honorary law license. If he were alive, he could have practiced law in Missouri.

See also

- List of Alpha Phi Alpha brothers

- List of people who disappeared mysteriously: pre-1970

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |