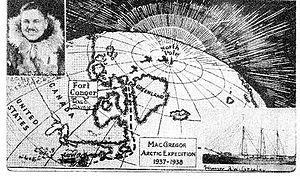

MacGregor Arctic Expedition facts for kids

The MacGregor Arctic Expedition was a special trip to the Arctic. It was paid for by private people, not the government. The main goal was to go back to Fort Conger on Ellesmere Island in Canada. This place was close enough to the North Pole for flying.

The expedition lasted from July 1, 1937, to October 3, 1938. It had four big goals:

- To gather information about the weather.

- To study Earth's magnetic field.

- To take pictures of the aurora borealis (Northern Lights) and see how they affected radio signals.

- To explore the area northwest of Ellesmere Island. They wanted to find out if a place called Crocker Land, which Robert Peary had put on maps, really existed.

Contents

Getting Ready for the Trip

In the spring of 1937, the team bought a three-mast ship called Donald II in Nova Scotia. They brought it to Port Newark in New Jersey. There, they put in new engines and made the ship stronger for the icy Arctic waters.

On May 2, 1937, the ship was renamed the Gen. A. W. Greely. This was to honor Adolphus Greely, who led an earlier Arctic trip in 1881 and 1882.

The expedition had eleven original members. Each person helped by bringing needed equipment or money. The team included:

- Clifford J. MacGregor, a weather expert from the US Weather Bureau.

- Isaac "Ike" Schlossbach, who was second in command, a navigator, and the main airplane pilot.

- Roy Fitzsimmons, a scientist who studied Earth's magnetism.

- Robert Danskin, who supplied the airplane and was a rock expert.

- Gerry Sayre, a radio engineer.

- Murray A. Wiener, the photographer.

- John Johnson, the cook and mechanic.

- Paul "Fuzzy" Furlong, another mechanic and dog handler.

- Francis Lawrence, who studied the air and was a Junior Naval Guard.

- Robert Inglis, a surveyor and Boy Scout (the youngest member).

- Norman Hortman, a pilot who left the trip early in Nova Scotia.

Heading North

The expedition started its journey from Port Newark, New Jersey, on July 1, 1937. They stopped twice in Nova Scotia. First, in Lunenburg to drop off some people and get fresh food. Then, in Sydney to drop off Norm Hortman and a radio technician. They also picked up coal there.

Next, they made two planned stops in Greenland. They got fresh water and food at Fairhaven. At Idglorssuit, Umank Fjord, they picked up dogs and gave gifts to the Inuit people.

After leaving Idglorsuit, the ship ran into thick ice in Baffin Bay. They were completely stopped by a wall of ice about 15 feet (4.6 meters) thick. Not being able to reach Fort Conger was a big letdown for MacGregor.

They tried to find a safe place on Ellesmere Island, but the whole coast was blocked by ice. They then drifted south along the coast of Greenland. They urgently looked for a place to spend the winter because new ice was already forming. There was a danger of the ship getting stuck in the ice.

Wintering in Etah, Greenland

The ship arrived at Foulke Fiord, near Etah, on August 31, 1937. Before the team could settle on land, they had several dangerous problems. These almost sank the ship. Their maps showed 40 feet (12 meters) of water, but the ship, which needed 12 feet (3.7 meters), got stuck. They had to unload some supplies to get the ship floating again at the next high tide.

On September 1, 1937, a strong storm blew the ship out to sea because the anchor couldn't hold on the rocky bottom. When they tried to return to Etah, one of the engines caught fire! Everyone was worried because there was still gasoline, ammunition, and dynamite on board. Luckily, they put out the fire.

After two days, they got back to Reindeer Point near Etah. But they found that most of the supplies they had unloaded earlier were now underwater. This was because the tide went up and down about 10 feet (3 meters) there. Finally, they unloaded everything and started making a cabin left by an earlier expedition bigger.

MacGregor was so sure his strong ship could reach Fort Conger that he hadn't gotten a permit from Danish officials. This permit was needed to set up a base camp in Greenland. Soon after New Year's, the local governor visited them. He had traveled a long way and knew about the expedition from their radio messages. He told them they had to leave as soon as possible.

What They Achieved

The team started taking weather observations every hour on September 8, 1937. They sent daily reports to the US Weather Bureau in Washington, D.C.. They also sent up balloons twice a day to study the air, except in December and January. All these observations continued until they sailed away on July 7, 1938.

MacGregor believed that carefully watching and mapping how air masses moved across the Arctic would help make better, longer-term Northern Hemispheric weather forecasts. In late 1937, MacGregor gave a long-range weather forecast for 1938 from Etah, Greenland. It turned out to be very accurate!

In February, Inuit people started arriving from the south. One of them was Ootah, who had gone with Peary in 1909 on the first trip to the North Pole.

In March, another group of explorers, the Haig-Thomas, Wright, Hamilton expedition, visited. They shared the hut while mapping parts of Ellesmere Island and studying plants and animals and glaciers. Together, Schlossbach and Wright surveyed a 300-mile (480 km) ice cap northeast of Etah. This was probably the longest continuous trip over that area at the time.

Paul Furlong and Roy Fitzsimmons traveled across Smith Sound to Cape Sabline on Ellesmere Island. They left supplies there at a Royal Canadian Mounted Police storage site. This was a request from Charles Camsell, the Commissioner of the Northwest Territories.

The MacGregor expedition brought a 1933 model Waco biplane with them. They used it for surveying and exploring. The plane had a single, 210-horsepower Continental engine. Schlossbach flew the Waco four times from Etah, making some important aviation achievements:

- The first solo flight over Ellesmere Island.

- The first landing on Ellesmere Island.

- Proving that Peary's claim of another island northwest of Ellesmere Island was wrong.

In 1909, while exploring the coast of Ellesmere Island, Robert Peary thought he saw a gray shadow far away. He believed he had found a new island and named it Crocker Land. Isaac Schlossbach, with a special sun compass and extra fuel, tried to find Crocker Land from the air. He flew back and forth over the area where Peary said Crocker Land was. All he saw was ocean; there was no Crocker Land.

The Journey Home

When the ice finally broke in July 1938, the explorers left Greenland. They made a quick stop in Thule to pick up John Johnson, who had been taken there earlier by dog sled for medical care.

The harsh winter had damaged the schooner more than they expected. An ice jam in Baffin Bay held the ship for weeks, drifting with the ice. Several parts of the ship started leaking, and they had to pump water out constantly for days. They finally reached St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador, where they made repairs.

During the trip from St. John's to Newark, off the Grand Banks, they faced a terrible storm. On September 21, 1938, they ran into one of the worst hurricanes that had ever moved up the Atlantic Coast. The expedition finally returned to Port Newark on October 4, 1938. They had been away for fifteen months and four days.

After the Expedition

The MacGregor Arctic Expedition had only ten members and a small budget. So, it wasn't as big as the trips led by Byrd or Scott. But it was similar in size and goals to many other polar expeditions of its time.

Besides its scientific and aviation achievements, the 15-month MacGregor Arctic Expedition was a valuable experience for several members. Many of them went on other polar expeditions later. Ike Schlossbach continued to go on expeditions until he was 70 years old. Paul Furlong joined another trip in 1939. Roy Fitzsimmons went on the United States Antarctic Service Expedition from 1939 to 1941. Murray Wiener joined Byrd on several trips and worked for him personally.

Hal Vogel said about the expedition: "The MacGregor Arctic Expedition had some notable achievements. Probably the most notable is its obscurity. Unlike most of its contemporaries, the MacGregor Arctic Expedition is virtually unrecorded in polar history."

Crew

- Clifford J. MacGregor - Commander and Weather Expert

- Commander, US Navy Reserve

- US Weather Bureau

- Newark, NJ

- Isaac Schlossbach - Second in Command, Navigator, Airplane Pilot

- US Naval Academy, Annapolis, MD

- Lieutenant Commander – US Navy (retired)

- Also on the Nautelis Arctic Expedition and Second Byrd Antarctic Expedition

- Neptune, NJ

- Roy G. Fitzsimmons – Geophysicist and Magnetologist

- Seaton Hall College, Class of 1937, Physics

- Carnige Institution, Magnetology

- Captain - US Army Air Force

- Newark, NJ

- Robert Sterling Danskin – Aircraft Supplier and Geologist

- Burdett College class of 1929

- Arlington, MA

- Albert Gerald Sayre – Radio Engineer

- Commander US Navy Reserve

- Cornwall On Hudson, New York

- Murray A. Wiener—Photographer

- Bradley Beach, NJ

- John Johnson – Cook and Mechanic

- Farmingdale, NJ

- Robert Inglis Jr. – Assistant Surveyor

- Boy Scout

- Trenton, NJ

- Paul B. "Fuzzy" Furlong – Mechanic and Dog Handler

- Upper Montclair, NJ

- Francis D. Lawrence – Aerologist (air scientist)

- Junior Naval Guard

- East Orange, NJ

- Norman Hortman - Pilot

- (Left the trip in Sydney, Nova Scotia)

See also

In Spanish: Expedición Ártica MacGregor para niños

In Spanish: Expedición Ártica MacGregor para niños