Magonista rebellion of 1911 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Magonista Rebellion |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mexican Revolution | |||||||

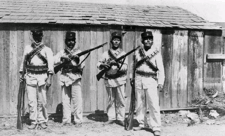

Magonista guerrillas with the banner, "Tierra y Libertad" in Tijuana, 1911. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Kiliwa | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~220 militia | 360 infantry ~200 militia |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ~20 killed ~10 wounded |

12 killed ~10 wounded 1 captured |

||||||

The Magonista rebellion of 1911 was an early uprising during the Mexican Revolution. It was organized by the Liberal Party of Mexico (PLM). This rebellion was only truly successful in northern Baja California. It gets its name from Ricardo Flores Magón, one of the main leaders of the PLM.

The Magonistas took control of Tijuana and Mexicali for about six months. This began with them taking Mexicali on January 29, 1911. The rebellion started against the rule of Porfirio Díaz, who was the president of Mexico. However, forces loyal to Francisco I. Madero later stopped the rebellion. Madero's agents gave a tip, and the leaders of the Magonista movement were arrested in the United States.

The PLM's Organizing Board planned and coordinated the rebellion from Los Angeles, California. Their goal was to create a free and libertarian area in Mexico. They hoped this area would be a starting point for a bigger social revolution across the country. They tried to put their ideas into action in Baja California. They also tried, to a lesser extent, in other states like Sonora and Chihuahua. Controlling the Baja peninsula was a backup plan. If they lost battles in the northern states, they could use Baja to regroup. Then they would move south and into other states.

In November 1910, Magonista and Maderista groups joined forces. They took important places in the northern states. But the two groups had different ideas, which soon led to conflicts. The Magonistas lost ground in Chihuahua. Some of their leaders were even arrested by Madero. This happened when they refused to accept him as provisional president. When some liberals regrouped in Baja California, they started a new campaign by capturing Mexicali.

Contents

What Was the Magonista Rebellion?

This uprising was part of a larger movement against the rule of Porfirio Díaz. But it soon moved away from the ideas of Madero, who wanted a more traditional democratic revolution. The Magonistas wanted to get rid of private property and create a worker's community.

Even though they held several cities for about half a year, their revolution was not very successful. The rebels faced problems like disagreements between Americans, Mexicans, and Native Americans. Also, some leaders were not very principled. Compared to the farming revolution in Morelos, the Baja California revolt did not achieve much.

However, the PLM's role in starting the revolution was important. Their ideas for the revolt in Baja California remained a strong part of the social changes of the Revolution. People who opposed the PLM tried to say that American interests controlled their movement. This was likely not true, but the accusation helped reduce their support.

Why Did the Rebellion Happen?

The tensions that led to the rebellion came from existing disagreements. These were between conservative and radical groups in Southern California and Northern Mexico. The PLM supported the Mexican Revolution. They wanted to overthrow Díaz's rule, free Baja California, and help indigenous peoples. They also opposed American businesses investing in Baja California. They saw this as another form of imperialism, where a stronger country takes control of a weaker one.

The PLM received a lot of support from radical groups in Southern California. Many American conservatives in California were worried. They feared losing their land if the anarchists succeeded. This made racial, political, and social tensions worse.

Before the revolution, the Magón brothers, Ricardo and Enrique, were forced to leave Mexico. This was because they criticized Díaz and called for social changes. But this did not stop them from trying to start a revolution. The Magón brothers moved the PLM's main office to Los Angeles. Here, they found allies in other left-wing groups. These included the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), Socialists, and trade unionists.

Through their speeches and activism, their ideas about anarchism spread widely. Because they supported unions and workers, the radicals gained popular support. The PLM especially appealed to migrant workers who had experienced harsh working conditions in Northern Mexico.

The PLM's main ally was the IWW in Los Angeles. This was especially true for dockworkers and migrant workers. These workers supported the PLM's strong organizing methods. They had also fought for control of the docks themselves. The IWW and the Socialist Party helped fund the PLM to start the revolution.

California had an "open shop" policy. This meant workers did not have to join a union. This policy made workers and unions unhappy. It created tension between workers and business owners. This atmosphere encouraged social radicalism among workers. Conservatives were alarmed by the radicals' plans and public support. They had invested a lot of money in Southern California and Baja California. They feared losing their land and property if the Magón brothers succeeded. This led many conservatives to speak out against the rebels, which made the divide between the two groups even deeper.

The media also made this divide worse. The Los Angeles Times, a conservative newspaper, called PLM supporters "wild-eyed-anarchists with smoking bombs in hand." The Regeneración, a revolutionary newspaper, published left-wing ideas. It also asked the public for support during the Mexican Revolution.

Since 1903, Colonel Celso Vega was the governor of the northern district. Like President Díaz, Colonel Vega was not well-liked by the people of Baja California.

The Revolution in Baja California

By 1906, the PLM had many operations in Mexico, the U.S. Southwest, and Southern California. Their second planned uprising in Mexico in June 1908 failed. This was because the Los Angeles Police Department arrested their leaders early. The Magón brothers were arrested but later released. The arrests, however, brought more local support in Los Angeles. Hundreds of protesters, including leaders of many labor groups, rallied around the brothers. This wide support caused a backlash from American conservatives and right-wing newspapers.

After their release, the Magón brothers and the PLM organized another rebellion. They planned to free Baja California from Díaz and California landowners. They wanted to return that land to the indigenous people who lived there before. However, even with popular support, the movement struggled to find enough volunteers to fight. Also, the rebels had little ammunition and not much money to buy more.

In 1910, the PLM's Organizing Board sent Fernando Palomares and Pedro Ramírez Caule. They met with indigenous leaders Camilo Jiménez and Antonio Cholay. Their goal was to create maps and organize indigenous groups for armed struggle. They gained the support of the Cocopah, Paipai, Kumeyaay, and Kiliwa peoples. The PLM Board in Los Angeles coordinated propaganda, funding, recruiting, and planning for the attack on Baja California. In 1911, the towns in northern Baja California were small: 1027 people in Ensenada, 300 in Mexicali, 100 in Tijuana, and less than 100 in Los Algodones and Tecate.

The Liberal Army paid its soldiers 1 peso a day. Officers received a bit more than federal army officers. Because Baja California had few people, they recruited many foreigners living in the United States. Some historians believe recruits were offered 100 to 600 US dollars in gold and 160 acres of farmland. However, it's more likely that recruitment managers made these offers, not the PLM Board.

Taking Mexicali

The PLM campaign in Baja California began on January 29, 1911. About 30 rebels, led by José María Leyva and Simón Berthold, took the town of Mexicali without a fight. They opened the jail, took over the barracks, and seized government money. Most Mexicali residents crossed into Calexico and stayed there until June. Other settlers joined the rebels, as did many foreign socialists and anarchists. Many of these were members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

On February 15, PLM forces fought and defeated federal troops led by Colonel Celso Vega. This victory boosted the rebels' spirits and numbers. By the end of February, there were about 200 armed men, both Mexicans and foreigners. In total, the Magonista forces reached 500 men. About 100 of these were Americans, including IWW members Frank Little and Joe Hill.

The U.S. government in Calexico and Yuma offered military help to the Mexican government. This was to protect hydraulic works built by American engineers on the Colorado River. The British sent two ships, the HMS Shearwater and the HMS Algerine. They aimed to occupy San Quintín to protect British interests from the Magonistas.

On February 21, 60 members of the Liberal Army, led by William Stanley, took the customs house of Los Algodones. A few days later, another group of liberals, led by José María Cardoza, stormed a construction camp. They got supplies, weapons, and new recruits from the workers.

In March, the liberals attacked Tecate twice but were pushed back both times. Then they marched to El Alamo, southeast of Ensenada. About 200 rebels managed to take the town square. Simón Berthold was badly wounded there and died days later. William Stanley also died in a fight with federal troops near Mexicali.

More foreigners were in the Liberal Army than Mexicans at this time. Anglo-Saxons often disobeyed Mexican officers. Orders from the PLM Board in Los Angeles were often stopped by authorities. This made coordinating the campaign harder. The Board appointed Carl Ap Rhys Pryce to fight the federal forces. But Pryce decided to go to Tijuana in early May. He thought it would be a good place to attack Ensenada later. He left another group to defend Mexicali.

In April, Mexican authorities reported about 400 rebels active in the Mexicali Valley. In late April, 126 Magonistas led by John R. Mosby took Tecate without a fight. On May 2, the liberals camped at El Carrizo ranch, south of Tecate. Federal forces attacked them there, and Mosby was wounded. He was taken to the U.S. side of Tecate for treatment. Sam Wood, an IWW member, was chosen as interim chief. The group then moved to Tijuana to join Pryce's column.

On May 20, Enrique Flores Magón wrote in The Regeneración that the rebels had built a small library in Mexicali. Everyone could go there to learn. The Conquest of Bread by Peter Kropotkin was like a guide for their temporary revolutionary communities.

Taking Tijuana and Ensenada

On May 8, 1911, the Second Division of the Mexican Liberal Army, led by Pryce, took Tijuana. On May 13, they took the town of San Quintín from the British.

On May 8, Ciudad Juárez was attacked by Maderista forces. On May 10, the city was surrendered to the federal forces. The capture of Ciudad Juárez led to an agreement on May 21. President Díaz agreed to resign. His foreign relations secretary, Francisco León de la Barra, became interim president. This agreement aimed to end fighting between the government and Madero's revolution.

The liberals called Madero a traitor and rejected the Treaty of Ciudad Juárez. De la Barra, who had spied on the PLM before, was tasked with disarming liberals who did not accept the peace treaties.

After this, the revolution slowed down. There were not enough volunteers, ammunition, or heavy weapons. Also, Berthold's death caused a leadership problem. The rebels were pushed back after a fight south of Tijuana. The rebellion finally ended when Mexican Federal forces, led by Colonel Celso Vega, took back Tijuana.

What Happened After the Rebellion?

Growing Distrust of Conservatives

The revolt did not achieve its goal of freeing Baja California. But it showed how popular radical groups were. This worried Californian conservatives. They strongly supported the "open shop" policy, which limited unions and workers' rights. The possibility of a rebel movement in California made conservatives more negative towards immigrants and working classes. They feared losing land, money, and profits. So, they spoke out even louder. After this event, conservatives linked Mexican rebels to labor strikes in Los Angeles. This led to increased discrimination and mistreatment of immigrants in Los Angeles. Tensions between different groups grew.

This also led the San Diego City Council to pass a rule against any public demonstrations.

Arrest of the Magón Brothers

After the rebels took these border towns, the Magón brothers were arrested again by the Los Angeles Police. They were charged with breaking U.S. neutrality laws. They were found guilty in July 1912 and sentenced to 23 months in jail. Many people worked to get Ricardo Flores Magón released, but he died in jail on November 21, 1922.

Decline of Leftist Groups

After Díaz lost power, a new president took over. With increased suspicion from conservatives, the power of radical groups in Southern California greatly decreased. The PLM split into different groups after the Magón brothers were arrested. One group still supported the Magón brothers. The other group supported the new president of Mexico. Also, the alliances the radicals had formed before the revolution fell apart. Many labor movements in Los Angeles also broke up.

Some members of the IWW made a final stand in the San Diego free speech fight of 1912. They protested a local ban on free speech and demonstrations. The police and groups who opposed them broke up the demonstration. This ended the remaining leftist movement in the region.

Images for kids

-

Campaign of the Liberal Party of Mexico in Baja California, 1911.

See also

In Spanish: Rebelión de Baja California para niños

In Spanish: Rebelión de Baja California para niños