Mary Louise Booth facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mary Louise Booth

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | April 19, 1831 Millville, New York, United States |

| Died | March 5, 1889 (aged 57) New York City |

| Occupation | Editor, translator, writer |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | American |

| Years active | 1845–1889 |

| Notable works | editor-in-chief, Harper's Bazaar |

| Partner | Mrs. Anne W. Wright |

Mary Louise Booth (born April 19, 1831 – died March 5, 1889) was an amazing American writer, editor, and translator. She made history as the very first editor-in-chief of Harper's Bazaar, a famous magazine for women.

When she was 18, Mary Louise moved to New York City. She learned to make vests to support herself. In her free time, she studied and wrote. She wrote stories and articles for newspapers and magazines. At first, she didn't get paid with money. Sometimes, she was paid with books, which she loved! She also reviewed books for journals.

Mary Louise worked hard and became very good at writing. She started getting more writing jobs. In 1859, she began writing a history of New York. Even then, she worked 12 hours a day but still couldn't earn enough money on her own. When she was 30, she became an assistant to Dr. J. Marion Sims. This was her first steady paying job. Finally, she could live in New York without her father's help.

In 1861, when the American Civil War began, Mary Louise found a French book called Uprising of a Great People. She worked almost non-stop, translating the entire book in less than a week! It was published very quickly and became a huge hit among people who supported the Union. Even Senator Charles Sumner and President Abraham Lincoln sent her thank-you letters. But again, she didn't earn much money for her hard work. During the war, she translated many French books that encouraged patriotic feelings. She even went to Washington, D.C. to write for important leaders.

After the Civil War, Mary Louise had proven herself as a talented writer. The Harper brothers offered her the job of editor for their new magazine, Harper's Bazaar. She started this role in 1867 and kept it until she died. She was a bit unsure at first, but she accepted the challenge. Thanks to her, the magazine became incredibly popular. It grew in influence and readers. People said she earned more money than any other woman in the United States at that time. She passed away on March 5, 1889, after a short illness.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Mary Louise Booth was born on April 19, 1831, in Millville, which is now Yaphank, New York. Her parents were William Chatfield Booth and Nancy Monswell.

Mary Louise's mother had French family roots. Her father's family came to America in 1649. One of his ancestors, John Booth, bought Shelter Island from Native Americans in 1652. Mary Louise also had a sister and two brothers. Her younger brother, Charles A. Booth, later became a Colonel in the army.

Mary Louise was a very smart child. She once said she couldn't remember learning to read French or English, just like she couldn't remember learning to talk! Her mother said that as soon as Mary Louise could walk, she followed her around with a book, begging to be taught to read stories. Before she was five, she had already read the entire Bible. She also read Plutarch and, by age seven, had mastered Racine in French. Then she started learning Latin with her father.

From then on, she loved to read and spent more time with books than playing. Her father had a large library. Before she turned eleven, she had read books by famous historians like Hume and Gibbon.

Mary Louise went to school, and her parents made sure she got a good education. She was very good at languages and science. She didn't enjoy math as much. She often learned more by herself than in school. She taught herself French by finding a French beginner's book. She compared the French words to English ones. Later, she learned German the same way. Because she taught herself and didn't hear these languages spoken, she couldn't speak them. But she became so good at reading them that she could translate almost any book from French or German into English.

When Mary Louise was about 13, her family moved to Brooklyn, New York. Her father started the first public school there, and Mary helped him teach. Her father always worried about her being able to support herself. He often gave her money. In 1845 and 1846, she taught at her father's school in Williamsburg. But she stopped teaching because of her health and decided to focus on writing.

As she got older, Mary Louise was determined to become a professional writer. She was the oldest of four children. Her father felt he couldn't give her too much help, as his other children might also need support later. So, when she was 18, Mary Louise decided she needed to be in New York City for her writing career.

Early Writing Career

A friend who made vests offered to teach Mary Louise the trade. This helped her move to New York. She rented a small room in the city. She only went home on Sundays because traveling between Williamsburg and New York took a long time back then. Her parents always kept two rooms ready for her at their house. But her family didn't really understand her writing work, so she rarely talked about it at home.

Mary Louise wrote stories and articles for newspapers and magazines. She translated several books from French. These included The Marble-Worker's Manual (1856) and The Clock and Watch Maker's Manual. She also translated André Chénier by Joseph Méry and The King of the Mountains by Edmond François Valentin About for Emerson's Magazine. This magazine also published her own original articles. Next, she translated Secret History of the French Court by Victor Cousin (1859).

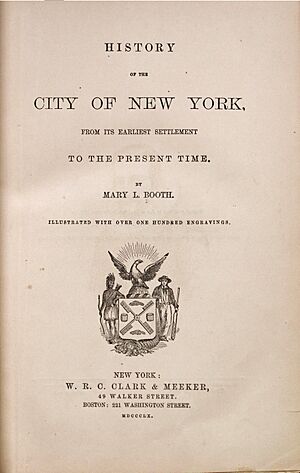

In the same year, her own book, History of the City of New York, was published. She did a lot of research for this book, and it was very important to her. She also helped Orlando Williams Wight translate French classic books. She translated About's Germaine (1860) as well.

A friend had suggested to Mary Louise that no complete history of New York City existed for schools. She started working on it. After some years, she finished a draft. A publisher then asked her to make it into a bigger book. While working, Mary Louise had full access to libraries and historical records. Famous writer Washington Irving sent her a letter of encouragement. Many other historians and experts helped her with documents. Historian Benson John Lossing wrote to her, "The citizens of New York owe you thanks for this popular story of the great city."

Mary Louise's history of New York City was published in one large book. It was so popular that the publisher suggested she travel to Europe. They wanted her to write histories of big European cities like London, Paris, Berlin, and Vienna. Her future as a writer looked very bright. However, the coming American Civil War and other events stopped her from traveling.

Helping During the Civil War

Soon after her history book came out, the Civil War began. Mary Louise had always been against slavery and supported ideas of progress. She strongly supported the Union side and wanted to help. She didn't feel she could be a nurse in military hospitals.

Then, she received an early copy of a French book called Un Grand Peuple Qui Se Releve ("Uprising of a Great People") by Count Agénor de Gasparin. She immediately saw how she could help. She took the book to publisher Charles Scribner I. He said he would publish it if she could translate it quickly, otherwise the war might be over. He said if she could finish it in a week, he would publish it. Mary Louise went home and worked tirelessly. She received proof pages at night and sent them back with new translations in the morning. In just one week, the translation was done. In two weeks, the book was published!

This book caused a huge stir during the war. Newspapers were full of reviews, both praising it and criticizing it, depending on their political side. Senator Sumner said, "It is worth a whole army in the fight for human freedom."

Translating this book connected Mary Louise with Gasparin and his wife. They invited her to visit them in Switzerland. A second edition of her history book was published in 1867, and a third, updated edition came out in 1880. Special large copies of her history book were bought by collectors. They added thousands of extra maps, letters, and pictures to them. One copy, made into nine huge volumes, was owned in New York City. Mary Louise owned another copy, which she had filled with over two thousand illustrations.

Mary Louise quickly translated more books. These included Gasparin's America before Europe (1861), Édouard René de Laboulaye's Paris in America (1865), and Augustin Cochin's Results of Emancipation and Results of Slavery (1862). For this work, she received praise from President Lincoln, Senator Sumner, and other important leaders. Throughout the war, she wrote letters to Cochin, Gasparin, Laboulaye, Henri Martin, and other Europeans who supported the Union.

She also translated other books by Countess de Gasparin and Count Gasparin. Documents sent to her by French friends of the Union were translated and published as pamphlets or in New York newspapers. Mary Louise translated Martin's History of France. Two volumes about The Age of Louis XIV came out in 1864. Two more, the last of the original 17 volumes, were published in 1866. She planned to translate the earlier volumes, but the project was stopped. Her shorter translation of Martin's History of France appeared in 1880. She also translated Laboulaye's Fairy Book, Jean Macé's Fairy Tales, and Blaise Pascal's Lettres provinciales (Provincial Letters). She received hundreds of thank-you letters from important people. In total, her translations filled nearly 40 books!

Leading Harper's Bazaar

In 1867, Mary Louise took on a new big job: managing Harper's Bazaar. This was a weekly magazine focused on making homes better and more enjoyable. She had a good relationship with the Harper brothers, who started and ran the magazine.

Under her leadership, Harper's Bazaar became very successful. It had hundreds of thousands of readers. She had assistants in every part of the magazine, but she was the main inspiration for everyone. The magazine had a big impact on American homes. Through its pages, Mary Louise influenced countless families for almost 16 years. She helped shape how a whole generation lived at home.

Personal Life

Mary Louise lived in New York City, near Central Park, in a house she owned. She lived with her longtime friend, Mrs. Anne W. Wright. Their friendship began when they were children. Their house was perfect for hosting guests. They always had visitors, and every Saturday night, their living room was filled with authors, singers, musicians, politicians, travelers, publishers, and journalists.

Mary Louise Booth died in New York on March 5, 1889, after a short illness.