Mummy Cave facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

Mummy Cave

|

|

The cave from a distance

|

|

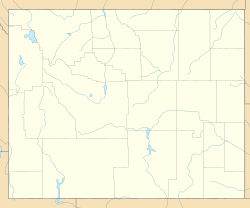

| Location | Along the North Fork of the Shoshone River, east of Yellowstone National Park Park County, Wyoming, United States |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Cody, Wyoming |

| NRHP reference No. | 81000611 |

| Added to NRHP | February 18, 1981 |

Mummy Cave is a special rock shelter and archaeological site located in Park County, Wyoming, United States. It's found close to the eastern entrance of Yellowstone National Park. This important site sits right next to U.S. Routes 14, 16, and 20. It's on the left side of the North Fork of the Shoshone River, about 6,310 feet (1,923 meters) high in the Shoshone National Forest.

The opening of Mummy Cave is about 150 feet (46 meters) wide. It goes back about 40 feet (12 meters) into a volcanic cliff. This cave is the biggest one known along the North Fork of the Shoshone River. Experts believe the river itself carved out the cave long ago.

People lived in Mummy Cave for a very long time, from about 7280 BC to AD 1580. A local person named Gene Smith found it in 1957. Scientists first studied it in 1962. The Buffalo Bill Center of the West later excavated the site. What makes Mummy Cave special is that it has many old items that usually don't last, like animal hides, feathers, and wood.

Researchers also found the mummified remains of a person inside the cave. They called this person "Mummy Joe." This mummy is about 1,200 years old, from around AD 800. The cave is also famous because its cultural layers go very deep, more than 28 feet (8.5 meters). These layers show that people used the cave often, maybe every year, for thousands of years. These layers cover periods from the Paleoindian time to the late Prehistoric period.

Contents

Exploring Mummy Cave's Geology

Even though it's called a "cave," Mummy Cave is actually a wide, shallow alcove. An alcove is like a large, open recess in a cliff. Its size and the strong rock around it make it deep. The roof of the alcove is about 50 feet (15 meters) above the river. The rock floor of the alcove is about 4 feet (1.2 meters) above the river.

When the cave was found, it was almost completely filled with alluvium. Alluvium is sand, silt, and clay carried and deposited by moving water. The cliff itself is made of Tertiary period tuff, which is volcanic ash. This ash is mixed with larger pieces of volcanic rock called breccia. The material filling the cave has built up for at least 10,000 years. It seems to have come from nearby debris fans. These fans form when weathered rock flows down channels in the cliffs.

Mummy Cave is also very dry. The pointed shape of the cliff above stops rain and melting snow from soaking through the rock into the cave. There are no cracks in the rock above that would let water in. This dryness helped preserve many old items.

How Scientists Studied Mummy Cave

The main study of Mummy Cave was led by Robert Edgar from 1963 to 1965. Scientists divided the alcove floor into a grid of 5-foot (1.5-meter) squares. They also set a permanent reference point for height on the wall. First, they worked to understand the different layers of soil and artifacts. This is called stratigraphy.

Once the layers were clear, they dug down layer by layer. They created terraces, or flat steps, in the cave floor. They used hand tools like trowels for layers with artifacts. For layers without artifacts, they used shovels. The dirt they removed was put down the embankment.

Before the scientists started, some people had already dug in the cave. These "relic hunters" had made a pit about 2.5 feet (0.76 meters) deep. This pit was in the area where the most artifacts were found. The relic hunters seemed to stop when they hit a pile of rocks. This rock pile turned out to be covering a human burial site.

By the end of 1963, part of the site was dug down 20 feet (6 meters). The top three cultural layers were removed from the whole site. In 1964, more layers were removed, and some areas were dug even deeper. By 1965, it was clear they would dig the entire depth of the site. They even used a bulldozer to move large amounts of dirt from outside the cave's drip line. Wilfred M. Husted directed the 1966 season. The findings from Mummy Cave were shared in the journal Science in 1968.

What Mummy Cave Taught Us

The digging at Mummy Cave found a nearly unbroken record of artifacts. These artifacts cover more than 9,000 years of history. Scientists could date these items in two ways. First, they used stratigraphy, which means dating them by their layer in the ground. Second, they used radiocarbon dating for exact ages. This continuous record has been very helpful for dating other archaeological sites in the Rocky Mountain region.

The stone projectile points found at Mummy Cave are especially important. They have become a standard for classifying old stone arrowheads and spearheads in the area. This helps scientists understand how different groups of people lived and traded across the American West. The layers and carbon dating show that people first lived in Mummy Cave near the end of the last ice age. Later, people lived there during a warmer period, then a cooler one after about 1000 BC.

The oldest layers in Mummy Cave had a few prismatic stone blades from about 7300 BC. Some layers had no artifacts, only soot from fires. Around 6500 BC, the cultural evidence became continuous. Layers 8, 9, 10, and 12 had lanceolate or leaf-shaped projectile points. These points are like the Angostura-style points. This suggests that the people living in Mummy Cave back then were big-game hunters from the Great Plains. They learned to hunt in the mountains.

In layer 16, dated to 5630 BC, a new type of point appeared. These Blackwater side-notched points suggest a new group of people arrived. They might have come from eastern Nebraska or western Iowa. The older group may have moved north. These points connect Mummy Cave to the Simonsen Site in Iowa, from the Early Archaic period. This change happened when the climate became warmer. Later, side-notched points in layers 21, 24, and 28 suggest the first group returned. The easterners had moved on to another area.

Layer 30 was dated to about 2470 BC. Layer 32 was dated to about 870 BC. Scientists think that layers 32 to 38 show the presence of Shoshonean people. From layer 36 onward, there are more clear Shoshonean items. These include cordage (ropes) and basketwork. Layer 38 had gray, flat-bottomed pottery made by Shoshonean people.

Layer 36 is famous for being where the "mummy" was found. The dried-out body of an adult male was found in this layer. He was covered by a sheepskin garment with fur and feather decorations. Radiocarbon dating showed he lived around AD 770.

Thousands of animal bones were found in Mummy Cave. Most could not be identified. But researchers at the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP) identified over two thousand bones. They found many bones from Bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) and deer (Odocoileus). What was very interesting was that there were many more sheep bones than deer bones. Eighty-eight sheep bones were found compared to fifteen deer bones. This is unusual because deer are usually more common in this area. This led UTEP researchers to think that Mummy Cave was a base camp for hunters who hunted at higher altitudes.

The wide variety of items found at Mummy Cave makes it a very important site for studying the history of the Rocky Mountains. The National Park Service recognized its importance. They placed it on the National Register of Historic Places in 1981.

Images for kids

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |