Nationalities and regions of Spain facts for kids

Spain is a diverse country made up of different areas. These areas have their own economies, social structures, languages, and unique histories. According to Spain's current rulebook, the Constitution of 1978, Spain is one country for all Spaniards. But it also says that this country is made of "nationalities and regions." The Constitution promises these areas the right to govern themselves.

The words nationalities and historical nationalities are used in Spain. They describe areas where people have a strong, long-standing identity. These are often autonomous communities (like states or provinces) whose local laws recognize their special history and culture. The Constitution of 1978 was the first time the word "nationality" was used in Spanish law. It was understood to mean Galicia, the Basque Country, and Catalonia. These areas had strong demands for self-rule.

Today, places like Aragon, the Valencian Community, the Balearic Islands, the Canary Islands, and Andalusia are also called "nationalities." Other areas, like Castile-La Mancha and Murcia, are called historical "regions." Asturias, Cantabria, and Castile and León are "historical communities." Navarre is special because it kept its old medieval laws. Madrid is the capital and was created as a community for the nation's interest.

Contents

Spain's Historical Journey

Spain's history shows how different kingdoms slowly came together. This is why some areas have strong local identities. For a long time, Spain did not try to control everything from one central place. This changed in the 1700s when the government became more centralized, like in other European countries.

In the 1800s, Catalonia and the Basque Country grew quickly with new factories and businesses. Other parts of Spain remained mostly farming areas. Because of this growth, people in Catalonia and the Basque Country started to feel a stronger sense of their own identity. They began to think of themselves as having their own "fatherland" or even "nation."

These areas were richer and had more people who could read. They also had their own languages: Catalan and Basque language. People worked hard to bring these languages back into use. They also explored their regions' histories. Catalonia remembered its past as a powerful Mediterranean empire. The Basque Country looked into its mysterious origins.

In the past, Catalonia and the Basque provinces had a lot of freedom. But later, they lost much of this independence. Only the Basque Country and Navarre kept some financial freedom. The economic growth in these areas made their local identities even stronger.

In the early 1900s, people in Galicia, Catalonia, and the Basque Country began to demand more self-government. Some even wanted complete independence. This was happening as Spaniards also thought about what it meant to be Spanish. Some believed Spain was defined by its Catholic faith and monarchy. Others thought power should come from the people.

Spain tried decentralization (giving power to local areas) in the First Spanish Republic (1873-1874). But this period was very chaotic and did not last. Later, the idea of Spanish nationalism grew stronger. It became a debate between the central government and the local areas.

In 1913, Catalonia was given some limited self-government. It was called the Commonwealth of Catalonia. But this was stopped in 1923.

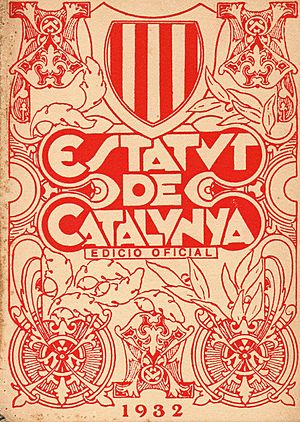

In 1931, the Second Spanish Republic was formed. Its new Constitution allowed regions to govern themselves. Catalonia was the first to get its own Statute of Autonomy. Its government, the Generalitat, was brought back. The Basque Country and Galicia also tried to get self-rule in 1936. But only the Basque Country's plan was approved before the Spanish Civil War began.

After the war, Franco's government (1939–1975) forced Spain to be very centralized. He tried to stop any local identities or languages. But this made people want democracy and recognition of their diverse identities even more.

After Franco died, Spain began its journey to democracy. The new leaders had to deal with the demands from Catalonia, the Basque Country, and Galicia. In 1977, over a million people marched in Barcelona. They demanded "liberty, amnesty, and a Statute of Autonomy." This was one of the biggest protests in Europe after the war.

A law was passed to create "pre-autonomies," or temporary local governments. Catalonia and the Basque Country were among the first to get these.

"Nationalities" in the 1978 Constitution

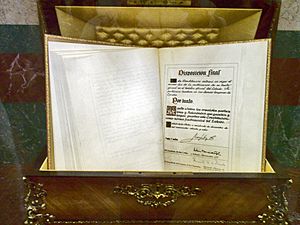

Recognizing the unique identities of Catalonia, the Basque Country, and Galicia was a big challenge for the new Parliament. The second article of the Constitution, which recognized "nationalities and regions," was heavily debated. Some on the right did not want it. Nationalists and the left insisted on it.

The debate also included the word "nation." Some believed there was only one Spanish "nation." Others wanted Spain to be a "plurinational State," meaning a state with several nations. In the end, Article 2 was passed. It used the term "nationalities" but strongly emphasized Spain's "indissoluble unity."

The article states:

The Constitution is based on the indissoluble unity of the Spanish nation, the common and indivisible country of all Spaniards; it recognises and guarantees the right to autonomy of the nationalities and regions of which it is composed, and the solidarity amongst them all

– Second Article of the Spanish Constitution of 1978

This article tried to bring together two ideas in Spain: central control and local self-rule. One of the Constitution's writers, Jordi Solé Tura, said it was a "meeting point" for different ideas of Spain. It aimed to answer the demands for self-rule that had been silenced for 40 years.

The Constitution did not clearly define "nationalities." But it was understood to mean areas with strong cultural, historical, or political identities.

The Constitution also said that Spain would protect "all Spaniards and the peoples of Spain in the exercise of their human rights, cultures traditions, languages and institutions." This was important because the "historical nationalities" have their own regional languages. The Constitution made Spanish the official language of the whole country. But it also said that "other Spanish languages" would be official in their own autonomous communities. It declared that Spain's different languages are a valuable heritage to be protected.

Spain's System of Autonomies

The Constitution aimed to give self-government to both "nationalities" and "regions." These would become "autonomous communities." But there was a difference in how they would get self-government and how much power they would receive. The three "historic nationalities" (Catalonia, Galicia, and the Basque Country) had a faster way to get full self-rule. Other regions had to follow a slower process. This meant the system was designed to be different for different areas.

Autonomous communities were formed from existing provinces. A community could be created by one or more provinces with shared history, culture, and economy. The Constitution did not say how many communities there would be or what their names would be. It also made the process voluntary. Regions could choose to become self-governing or not. This unique system of local administration was called the "State of Autonomies." It is very decentralized, but it is not a federation (like the United States).

While the Constitution was being written, Andalusia also demanded to be recognized as a "nationality." It wanted to get self-government quickly too. This led to a policy called "café para todos" (coffee for all). This meant that all regions would get roughly the same level of self-government, even if at different speeds.

Catalonia, the Basque Country, and Galicia got full self-rule quickly. Andalusia started this process after a vote in 1980. Other regions followed a slower path, getting less power at first. After five years, they would gradually gain more powers.

A special exception was made for the Basque Country and Navarre. They got back their fueros, or "medieval charters," which gave them financial independence. Navarre chose not to join the Basque Country. Instead, it became a "chartered community" because of its old laws.

The Basque Country and Navarre are "communities of chartered regime" because they collect their own taxes. They then send a set amount to the central government. Other communities are "common regime." They only partly control their taxes. The central government collects taxes from these communities and shares them out to ensure fair funding for all.

Spain Today

By 1983, 17 autonomous communities were created across Spain. (Later, two autonomous cities, Ceuta and Melilla, were also created.) All communities follow the old provincial borders. Many communities also match historical regions from centuries ago.

However, some autonomous communities are new creations. For example, Cantabria and La Rioja were historically part of Castile. But people in these areas strongly supported becoming new entities. The province of Madrid was also separated from New Castile and became its own autonomous community. This was partly because Madrid is the capital.

As all communities gained similar powers, some people felt there was little difference between "nationality" and "region." This is welcomed by some national political parties. Other communities, like Andalusia, Aragon, the Balearic Islands, the Canary Islands, and the Valencian Community, are also called "historical nationalities." Many communities that do not have financial independence often follow Catalonia's lead in asking for more powers. This has led to new debates about whether "nationalities" should be called "nations."

In 2003, the Basque Country's government proposed a plan to become a "free associated State" of Spain. But the Spanish Parliament rejected this. In 2006, the Catalan Parliament voted to call Catalonia a "nation" in its new Statute of Autonomy. The Spanish Parliament removed this word. But it did mention in the document's introduction that the Catalan Parliament had chosen to call Catalonia a "nation." It also said the Constitution recognizes Catalonia's "national reality" as a "nationality."

The fact that the Basque Country and Navarre have financial independence has caused unhappiness in Catalonia. Catalonia wants the same privilege. Catalonia contributes a lot of money to the central government and feels it has a large financial deficit.

"Nationalities" have also played a big role in national politics. When no major party wins a clear majority in Parliament, they often make agreements with "nationalist" (regional) parties. This sometimes leads to more powers being given to the peripheral nationalities.

Most people in Spain are happy with the system of autonomies. This is especially true in Catalonia and Galicia. In the Basque Country, some still question Spain's legitimacy. But even there, most people are satisfied. However, in all three "historical nationalities," many people still want Spain to become a true federal State. Some also want the right to self-determination and independence.

Since the economic crisis began in 2008, different communities have reacted differently. Some communities want to give back some powers to the central government. But in Catalonia, the tough financial situation has caused great anger. Many people feel the large financial deficit is unfair. This has led many, even those not usually wanting independence, to support leaving Spain.

Support for independence in Catalonia doubled from 2008 to 2012. In September 2012, about 600,000 to two million people marched in Barcelona for independence. This was one of the largest protests in Spanish history.

After the rally, Catalonia's president, Artur Mas, asked Spain's prime minister for a new tax system for Catalonia. This would have been like the one in the two communities of chartered regime. But the prime minister said no, calling it unconstitutional. Mas then called for early elections in Catalonia. Before that, the Catalan parliament approved a plan for a vote on self-determination in the next four years. This would let people decide if Catalonia should become an independent state.

Spain's government said it would use "all legal instruments" to block such a vote. Leaders of other parties in Spain also do not support Catalonia leaving. Instead, they want to change the Constitution to create a true federal system in Spain. They believe this would "better reflect the singularities" of Catalonia.

In December 2012, a counter-protest was held in Barcelona. It gathered many people under Spanish and Catalan flags.

See also

In Spanish: Nacionalidad histórica para niños

In Spanish: Nacionalidad histórica para niños

- Andalusian nationalism

- Basque nationalism

- Catalan nationalism

- Galician nationalism

- National and regional identity in Spain

- Political divisions of Spain

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |