Francoist Spain facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Spanish State

Estado Español (Spanish) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1936–1975 | |||||||||||

|

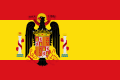

Flag

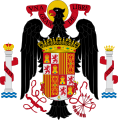

(1945–1977) Coat of arms

(1945–1977) |

|||||||||||

|

Anthem: Marcha Granadera

("Grenadier March") |

|||||||||||

Territories and colonies of the Spanish State:

|

|||||||||||

| Capital and largest city

|

Madrid | ||||||||||

| Official languages | Spanish | ||||||||||

| Religion | Catholicism (official); under the doctrine of National Catholicism |

||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Spanish, Spaniard | ||||||||||

| Government | Unitary Francoist one-party personalist dictatorship | ||||||||||

| Caudillo | |||||||||||

|

• 1936–1975

|

Francisco Franco | ||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||

|

• 1938–1973

|

Francisco Franco | ||||||||||

|

• 1973

|

Luis Carrero Blanco | ||||||||||

|

• 1973–1975

|

Carlos Arias Navarro | ||||||||||

| Prince | |||||||||||

|

• 1969–1975

|

Juan Carlos I | ||||||||||

| Legislature | Cortes Españolas | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Interwar period • World War II • Cold War | ||||||||||

| 17 July 1936 | |||||||||||

| 1 April 1939 | |||||||||||

|

• Succession law

|

6 July 1947 | ||||||||||

|

• UN membership

|

14 December 1955 | ||||||||||

|

• Organic Law

|

1 January 1967 | ||||||||||

| 20 November 1975 | |||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

| 1940 | 856,045 km2 (330,521 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

|

• 1940

|

25,877,971 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Spanish peseta | ||||||||||

| Calling code | +34 | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| Today part of | Equatorial Guinea Morocco Spain Western Sahara |

||||||||||

Francoist Spain (Spanish: España franquista) was a period in Spanish history from 1936 to 1975. During this time, Francisco Franco ruled Spain as a dictator, holding the title of Caudillo. After his death in 1975, Spain began its journey to become a democracy. This era was officially known as the Spanish State (Spanish: Estado Español).

The way the government worked changed over the years. Franco became the main leader of the rebel forces during the Spanish Civil War in 1936. By 1939, his rule covered the whole country. At first, his government was very strict, similar to fascist regimes in other parts of Europe. It controlled many parts of life, including the economy and how people worked.

During World War II, Spain stayed neutral, meaning it didn't officially join either side. However, it did support the Axis powers (like Germany and Italy) in some ways. Because of this, many countries avoided Spain for about ten years after the war. Spain's economy, which was still recovering from the Civil War, struggled a lot during this time. In 1947, a law was passed that made Spain a kingdom again, but Franco remained the head of state for life. He had the power to choose the next king.

In the 1950s, Spain started to change. The economy opened up, and new leaders helped it grow very quickly. This period of fast growth was called the "Spanish miracle". Spain also became less isolated. It joined the United Nations in 1955. During the Cold War, Franco was seen as a strong opponent of communism, so Western countries, especially the United States, started to support his government. Franco died in 1975. Before his death, he chose Juan Carlos I to be the new King, who then helped Spain become a democracy.

Contents

How Franco's Government Began

On October 1, 1936, Franco was officially named Caudillo of Spain. This title was similar to "Duce" in Italy or "Führer" in Germany. He was given this power by the group that controlled the areas held by the Nationalists. In 1937, Franco took control of the main political party that supported his side, the Falange Española de las JONS. He combined it with another group to form the Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las JONS. This became the only legal political party in Francoist Spain.

Franco's government took control of Spain by defeating those who supported the previous government. They imprisoned or executed many people who believed in things like regional self-rule, democracy, or women's rights. These people were seen as "enemy elements." After the Civil War ended in 1939, over 270,000 people were in prisons, and about 500,000 had left Spain. Many who fled were forced to return or ended up in concentration camps in other countries.

Spain's close ties with the Axis powers led to its isolation after World War II. It did not join the United Nations until 1955. However, the start of the Cold War changed things. Franco's strong opposition to communism made his government an ally of the United States. During this time, independent political parties and worker groups were banned. But by the late 1950s, Spain began to receive a lot of foreign investment. This led to a period of very fast economic growth.

In 1947, Spain was declared a kingdom again. But no king was chosen until 1969, when Franco named Juan Carlos of Bourbon as his future successor. Franco died on November 20, 1975. Juan Carlos then became King of Spain and led the country towards democracy.

How the Government Worked

After Franco won the Civil War in 1939, the Falange party became the only legal political party in Spain. Franco had a lot of power, more than any Spanish leader before or since. He didn't even need to ask his cabinet (a group of advisors) for most laws. Some historians say he had more daily power than leaders like Adolf Hitler or Joseph Stalin.

Franco's government was very centralized. This means that most decisions were made by the central government in Madrid, with little power given to local areas. In 1942, a new law created the Cortes Españolas, which was a kind of parliament. However, this parliament could only give advice; it didn't have real power to make laws or control government spending. Franco alone appointed and removed ministers.

A law passed in 1945 said that all "fundamental laws" had to be approved by a public vote. However, only heads of families could vote. Local councils were also chosen in a similar way, and mayors were appointed by the government.

Franco used this system to decide who would be the next leader. He waited a long time to choose a king. In 1969, he chose Juan Carlos of Bourbon, the grandson of the last king, to be his official heir.

In 1973, because of his old age, Franco stepped down as Prime Minister. He appointed Navy Admiral Luis Carrero Blanco to take his place. However, Carrero Blanco was killed that same year. Carlos Arias Navarro then became the new Prime Minister. Franco remained the Head of State until his death in 1975.

Military Forces

After the Civil War, Franco greatly reduced the size of the Spanish Army. It went from nearly one million soldiers to about 250,000 by 1940. However, due to concerns about World War II, he increased the army's size again. By 1942, the army had over 750,000 men. The Air Force and Navy also grew. The army remained strong with about 400,000 men until the end of World War II.

Colonial Empire and Decolonisation

Spain tried to keep control of its remaining colonies during Franco's rule. However, Franco had to give up some of these territories. When the French protectorate in Morocco became independent in 1956, Spain also gave up its part of Morocco. In 1968, under pressure from the United Nations, Franco granted independence to Spain's colony of Equatorial Guinea. The next year, he gave the area of Ifni to Morocco.

Spain also tried to gain control of Gibraltar, a British territory. Franco closed the border with Gibraltar in 1969, and it wasn't fully reopened until 1985. In 1975, Morocco took control of the former Spanish territories in the Sahara.

What Francoism Was Like

Franco's government was known as "Francoism." It was an authoritarian system, meaning it had a strong central leader and limited freedoms for people. It was also very anti-communist and promoted a strong sense of Spanish nationalism. The Catholic Church played a very important role in society and government.

Franco's government had several key features:

- Authoritarianism: All power was held by Franco.

- Anti-Communism: It was strongly against communism.

- Spanish Nationalism: It promoted a single Spanish identity.

- National Catholicism: The Catholic Church was the official religion and had a lot of influence.

- Monarchism: Spain was declared a kingdom, though Franco ruled as regent.

- Militarism: The military was very important.

Many experts describe Franco's regime as an "authoritarian regime with limited pluralism." This means that while there was some variety, the government still controlled most aspects of life.

How it Developed

The Falange party became the main political group during Franco's rule. It was the only legal party, but after World War II, it was often called the "National Movement" instead of a "party."

Authoritarian Rule

Franco's government was very strict. It controlled or banned all non-government worker groups and political opponents. The Guardia Civil, a military police force, patrolled towns and rural areas to maintain control. Larger cities had the Policía Armada, known as grises (greys) because of their uniforms.

Franco was also the center of a "personality cult." This meant that official messages taught people that he was a special leader sent to save the country.

Many groups were suppressed, including worker unions, communist and anarchist groups, liberal democrats, and groups seeking more self-rule for regions like Catalonia and the Basque Country. The main worker unions were outlawed and replaced by a government-controlled one. Political parties were banned. University students who wanted democracy protested in the late 1960s and early 1970s, but these protests were put down. The Basque separatist group ETA was formed in 1959 to fight against Franco's rule.

Spanish Nationalism

Franco's Spanish nationalism promoted a single national identity centered on Castilian culture. It tried to suppress Spain's diverse regional cultures. For example, bullfighting and flamenco were promoted as national traditions, while other regional traditions were discouraged. All cultural activities were censored, and many were forbidden. This policy became less strict in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Franco's government was very centralized. It removed the self-rule that the Second Spanish Republic had given to regions. It also took away special financial rights (called fueros) from two of the three Basque provinces. These rights were kept in the third Basque province and in Navarre because these areas had supported Franco during the Civil War.

Franco also used language policies to create a single national identity. Even though Franco himself was Galician, his government removed the official status of Basque, Galician, and Catalan languages. Spanish became the only official language for government, education, and public life. Using other languages was forbidden in schools, advertising, and public signs. While people still used these languages privately, their use was discouraged.

Roman Catholicism

Franco's government used religion to gain support, especially after World War II. Franco was often shown as a very religious Catholic and a strong defender of the Catholic Church, which was the official state religion. The government reversed many of the changes that had made Spain more secular (non-religious) under the previous Republic. The Church gained a lot of power and helped control the country's citizens.

The Church had a big role in schools. Crucifixes were put back in classrooms. The Ministry of Education was led by someone who wanted to make state schools more Catholic and gave a lot of money to Church schools. Teachers who supported progressive ideas were often fired.

Children whose parents had supported the Republic were sometimes taught in orphanages run by priests and nuns. They were told that their parents had done wrong things.

Franco's government promoted traditional roles for women. Women were expected to be loving daughters, sisters, and faithful wives, focusing on family and motherhood. Many laws passed by the Second Republic that aimed for equality between men and women were cancelled. Women could not become judges or testify in trials. Their financial matters often had to be managed by their fathers or husbands. These rules became somewhat less strict in the 1960s and 1970s.

In 1947, Franco declared Spain a monarchy, but he didn't name a king right away. He kept the throne empty and ruled as a regent (someone who rules for a king). This was done to please the groups who wanted a king. Franco himself used symbols of royalty, like wearing a captain-general's uniform and living in the Royal Palace. He was called Caudillo of Spain, by the Grace of God, a title usually used by kings.

The choice of Juan Carlos of Bourbon as Franco's successor in 1969 surprised many people. Juan Carlos was not the preferred choice for all royal supporters.

Women in Francoist Spain

Before Franco's rule, during the Second Republic, women had gained the right to vote and more legal equality. However, under Franco's government, the Catholic Church played a major role in society. The Church supported the idea that women should primarily focus on their families and homes.

All Spanish women were required to serve for six months in the Women's Section of the Falange party. Here, they were trained for motherhood and given political lessons. Official messages emphasized that women's main roles were family care and motherhood. Many laws that promoted equality were cancelled. For example, women could not become judges or give testimony in trials. Their financial decisions often needed approval from their fathers or husbands. Until the 1970s, a woman could not open a bank account without her father or husband signing for it. Some of these rules were relaxed in the 1960s and 1970s, but they remained in place until Franco's death.

Media Control

Under a 1938 law, all newspapers were censored before they could be published. They were also forced to print any articles the government wanted. The government chose the main editors, and all journalists had to be registered. All media that supported liberal, republican, or left-wing ideas were banned.

The government created its own media network, including newspapers like Diario Arriba and Pueblo. Government news agencies were also created. The state radio, Radio Nacional de España, was the only one allowed to broadcast news bulletins, and all other radio stations had to play them. Short news films called No-Do were shown in all cinemas. The government television network, Televisión Española, started in 1956.

The Catholic Church also had its own media, including a newspaper and a radio network. Other media outlets supported the government. In 1966, a new law removed the strict pre-publication censorship, but criticizing the government was still a crime.

Economy Under Franco

The Civil War had badly damaged Spain's economy. For more than ten years after Franco's victory, the economy did not improve much. Franco first tried a policy called "autarky," which meant cutting off almost all international trade. This policy had very bad effects, and the economy struggled. Only those involved in the black market seemed to be doing well.

In 1940, the Sindicato Vertical was created. This was the only legal worker union, and it was controlled by the government. Other worker unions were forbidden.

By the late 1950s, Spain was almost bankrupt. Pressure from the United States (which provided aid) and international organizations helped convince Franco's government to open up the economy in 1959. This led to a period of rapid economic growth, known as the "Spanish Miracle". However, these economic changes were not matched by political reforms, and the strict control continued.

During the 1960s, Spain became much wealthier. International companies set up factories in Spain. Spain became one of the fastest-growing economies in the world. By the time Franco died, Spain had caught up a lot with other Western European countries in terms of living standards.

Franco's Legacy

Franco's legacy remains a topic of debate in Spain and other countries. Most statues of Franco and other public symbols of his regime have been removed. The last Franco statue in Madrid was taken down in 2005. In 2006, the European Parliament officially condemned the "multiple and serious violations" of human rights that happened under Franco's rule from 1939 to 1975. The resolution also asked for historians to have access to the archives of Franco's regime. It also suggested building monuments to remember the victims of Franco's rule.

In Spain, a group was formed in 2004 to honor the victims of Franco's regime. Franco's memory is especially disliked in Catalonia and the Basque Country because of his policies against their regional languages and cultures. These regions had strongly resisted Franco during and after the Civil War.

In 2008, a group started searching for mass graves of people who were executed during Franco's rule. A law called the Historical Memory Law was passed in 2007 to officially recognize the crimes against civilians and to help find these mass graves. Investigations have also begun into the abduction of children during the Franco years, which may have affected up to 300,000 children.

Flags and Symbols

Flags

After the Civil War, new flags were introduced for the army. These flags featured the eagle of Saint John on the shield. This eagle was inspired by the coat of arms used by the Catholic Monarchs after they took Granada. The new flag designs were officially set in 1945 and remained in use until 1977.

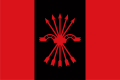

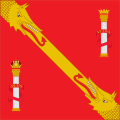

During Franco's time, two other flags were often displayed alongside the national flag:

- The flag of the Falange (red, black, and red vertical stripes with the yokes and arrows symbol).

- The traditionalist flag (white with the Cross of Burgundy in the middle).

These flags represented the "National Movement," which combined the different groups that supported Franco.

From Franco's death in 1975 until 1977, the national flag remained the same. In 1977, a new flag design was approved with a slightly different eagle and the motto "Una, Grande y Libre" ("One, Great and Free") moved to a new position.

- State flags

-

State flag (July 17, 1936 – August 29, 1936)

-

State flag (August 30, 1936 – 1938)

-

State flag (1938–1945)

-

State flag (1945–1977)

-

Civil flag (1936–1975)

- Party flags

-

Flag of the Falange Movement

-

Flag of the Traditionalist Movement (Carlism)

Standards

-

Standard of Francisco Franco (1940–1975)

Coat of Arms

In 1938, Franco adopted a new version of the coat of arms. It included elements from earlier Spanish history, like the Eagle of Saint John and the yoke and arrows symbols. This coat of arms featured symbols of Castile, León, Aragon, Navarre, and Granada, with the eagle and the Pillars of Hercules.

- State Coat of arms

-

Coat of arms (1936–1938)

-

Coat of arms (1938–1945)

-

Coat of arms (1945–1977)

- Personal Coat of arms

-

Coat of arms of Francisco Franco (1940–1975)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Dictadura de Francisco Franco para niños

In Spanish: Dictadura de Francisco Franco para niños