Navajo Generating Station facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Navajo Generating Station |

|

|---|---|

Navajo Generating Station

|

|

| Country | United States |

| Location | Navajo Nation, near Page, Arizona |

| Coordinates | 36°54′12″N 111°23′25″W / 36.90333°N 111.39028°W |

| Status | Shutdown |

| Commission date | 1974 1975 1976 |

| Decommission date | November 18, 2019 |

| Construction cost | $650 million (1976) ($2.44 billion in 2021 dollars ) |

| Owner(s) | U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (24.3%) Salt River Project (21.7%) LADWP (former) (21.2%) Arizona Public Service (14.0%) NV Energy (11.3%) Tucson Electric Power (7.5%) |

| Operator(s) | Salt River Project |

The Navajo Generating Station was a very large coal-fired power plant located on the Navajo Nation land, close to Page, Arizona, in the United States. This plant made electricity for homes and businesses in Arizona, Nevada, and California. It also powered the pumps for the Central Arizona Project, which brought a lot of water from the Colorado River to central and southern Arizona every year.

Even though it was expected to run for many more years, the companies that owned the plant decided in 2017 to close it when its land lease ended in 2019. The Navajo Nation tried to buy the plant to keep it running, but in March 2019, they stopped their efforts.

The plant officially stopped making electricity on November 18, 2019. Taking apart the whole site was expected to take about three years. On December 18, 2020, the three tall smokestacks were taken down.

Contents

History of the Power Plant

Why the Plant Was Built

Back in the 1950s and 1960s, more and more people were moving to places like southern California, Arizona, and Nevada. This meant they needed a lot more electricity! The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation also needed a huge amount of power to run the pumps for a big water project called the Central Arizona Project (CAP).

At first, people thought about building large dams on the Colorado River to make electricity. But these dams would have been very close to the Grand Canyon. Many groups, especially environmental ones, were against this idea. They suggested building a power plant that used heat or nuclear energy instead. Because of this, the dam plans were stopped, and the Navajo Power Project was started. This project included the Navajo Generating Station (NGS), a coal mine called Kayenta Mine, a special railroad to carry coal, and hundreds of miles of power lines.

The best place for the new power plant was chosen to be about six miles (10 km) east of Glen Canyon Dam and three miles (5 km) south of Lake Powell. This land was leased from the Navajo Nation. The spot was good because it was near a source of coal that wasn't too expensive and had a steady supply of water for cooling. The nearby city of Page and U.S. Highway 89 already had roads and other things needed to help build and run the plant.

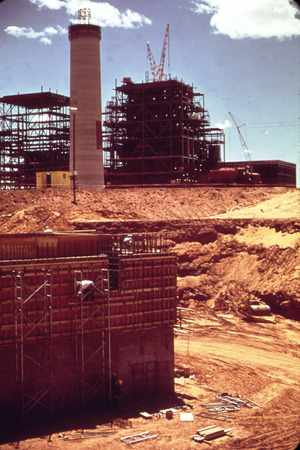

Construction began in April 1970. The first machine that made electricity was finished in 1974, the second in 1975, and the third in 1976. The total cost was about $650 million.

Protecting the Air

From 1977 to 1990, after new Clean Air Act rules were made, studies were done to see how the plant's emissions might affect the air in national parks and wilderness areas.

These studies showed that reducing sulfur dioxide (SO2) emissions could make the air clearer in the Grand Canyon. Sulfur dioxide is a gas that can cause air pollution and haze. So, the EPA suggested that the plant reduce its SO2 emissions by 70%.

However, the power plant and environmental groups worked together to find an even better and cheaper way. They agreed to reduce SO2 emissions by 90% by 1999. The EPA accepted this plan. To do this, the plant installed special equipment called "wet SO2 scrubbers." This project cost about $420 million.

Later, between 2003 and 2005, the plant also improved its electrostatic precipitators. These are devices that remove tiny particles like fly ash from the smoke.

In 2007, the plant also looked at ways to reduce nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions. Nitrogen oxides are another type of air pollutant. Even though there were no rules yet to reduce NOx, the plant voluntarily installed new burners in 2009, 2010, and 2011. These new burners helped reduce NOx emissions by more than 40%.

The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power left the project in 2016. Around this time, making electricity from natural gas became cheaper than using coal for the Navajo Generating Station. This meant the plant made less electricity. The owners wanted any new owner, like the Navajo Nation, to take on the responsibility of cleaning up the site in the future.

How the Plant Worked

Design and Power Production

The Navajo Generating Station had three large machines, each able to make 750 megawatts of electricity. The main parts of each machine included a boiler, a turbine, a generator, and equipment to control pollution.

The boilers, made by Combustion Engineering, heated water to create very hot, high-pressure steam. This steam was then sent to the turbines. Each boiler could produce over 5 million pounds of steam per hour!

The main turbines, made by General Electric, were spun by the steam. The turbines were connected to generators, which then made electricity.

After spinning the turbines, the steam went into a condenser. Here, water circulating through tubes cooled the steam, turning it back into water. This water was then reused. The heat from the steam was released into the air using six large cooling towers.

The plant used about 26,000 acre-feet of water from Lake Powell each year. This is mainly for cooling and for the scrubbers that clean the air.

Fuel Source

The plant used about 8 million tons of coal each year. This coal came from the Peabody Energy's Kayenta mine, which was about 75 miles away. A special railroad, called the Black Mesa and Lake Powell Railroad, owned and operated by the plant, carried the coal from the mine to the power station. The coal used had a low amount of sulfur (0.64%) and about 10.6% ash.

Tall Smokestacks

The plant had three very tall flue gas stacks, each 775 feet (236 meters) high. These were among the tallest structures in Arizona. The stacks were made of strong concrete with a metal lining inside. The plant's original stacks were replaced in the late 1990s with new, wider ones of the same height. This was needed because the new scrubbers made the smoke cooler and wetter.

Plant Performance

The plant could make a total of 2,250 megawatts of electricity. This is the power that left the plant through the power lines. The plant also used some power for its own operations.

In 2011, the plant made about 16.9 terawatt-hours (TWh) of electricity. This means it ran at about 86% of its full power for the whole year.

However, by 2014, the amount of electricity it made dropped to 72% of its capacity, and in 2016, it was down to 61%. This was partly because natural gas became a cheaper way to make electricity.

Environmental Controls

Cleaning the Air

The plant had special equipment to clean the smoke (called flue gas) before it went into the air.

- Particulate Matter: Tiny particles, like fly ash, were removed from the smoke by electrostatic precipitators (ESPs). These removed 99% of the particles. The scrubbers removed even more.

- Sulfur Dioxide (SO2): This gas was controlled by "wet scrubbers." These scrubbers used limestone and water to remove over 92% of the SO2 from the smoke. Before these scrubbers were installed, the plant released about 71,000 tons of SO2 each year. The scrubbers used about 24 megawatts of power, 130,000 tons of limestone, and 3,000 acre-feet of water each year. They also produced 200,000 tons of gypsum (a material used in building).

- Nitrogen Oxides (NOx): These gases were controlled by special burners that reduced their formation during the burning of coal. Before 2009, the plant released about 34,000 tons of NOx each year. The new burners reduced this by about 14,000 tons per year, which is more than 40%.

- Carbon Dioxide (CO2): In 2015, the plant's carbon dioxide emissions were among the highest in the U.S. This was because it produced a lot of electricity. However, for each unit of electricity it made, its CO2 emissions were lower than 75% of other coal plants in the U.S. This was because it used a specific type of coal and was efficient.

- Mercury: In 2011, the plant released about 586 pounds (266 kg) of mercury.

| Component | Rate (pounds per million Btu) | Rate (pounds per MWh) | Annual total (short tons per year) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SO2 | 0.054 | 0.548 | 4,641 |

| NOx | 0.233 | 2.340 | 19,837 |

| CO2e | 219 | 2,201 | 18,660,820 |

Air Quality in the Area

The air quality in northern Arizona and the Colorado Plateau usually met the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS). These are rules set to protect public health.

The EPA's Air Quality Index (AQI) shows that there were no unhealthy air days for most people in northern Arizona and southern Utah. Even for people sensitive to ozone (like those with asthma), unhealthy days were rare.

Levels of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and carbon monoxide (CO) in the Page area were also much lower than the safety standards.

Tiny particles (PM2.5), which can affect health and visibility, were also very low in the Grand Canyon region. Visibility in the Grand Canyon area was also very good.

In 2012, there was a warning about eating striped bass from lower Lake Powell because of mercury. However, studies showed that the Navajo Generating Station contributed less than 2% of the mercury in the Colorado River watershed. Much of the mercury comes from natural sources like rocks.

New Rules for Emissions

In 2015, new rules called the Mercury and Air Toxics Standard (MATS) required the plant to reduce its mercury emissions even more.

In 2013, the EPA suggested new rules to further reduce NOx emissions. This would have meant the plant needed to install expensive new equipment called Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) by 2023. This equipment would reduce NOx by about 15,000 tons per year.

These SCR systems would have cost about $600 million to build and $12 million each year to run. They would also use more electricity, meaning the plant would burn more coal and release more CO2.

The plant faced many challenges in adding these new systems. The owners would have had to agree on new leases for the land, railroad, and power lines, and a new coal supply agreement. Some owners, like the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, could not invest in coal plants due to California law.

Eventually, the owners and other groups agreed that the plant would stop making electricity from coal by December 22, 2044, at the latest. However, because of changing energy prices and the high cost of upgrades, the plant closed much sooner.

Handling Wastewater

The Navajo Generating Station was one of the first power plants to have a "zero liquid discharge" (ZLD) system. This meant it reused all of its wastewater. Water from the cooling towers and other areas was cleaned and reused inside the plant.

Handling Waste Products

The plant sold about 500,000 tons of fly ash each year. Fly ash is a byproduct of burning coal and can be used to make concrete. Other waste products, like bottom ash and gypsum (from the scrubbers), were dried and buried on-site. The rules for burying this waste required it to be covered with at least two feet of soil to prevent erosion.

Economic Impact

The Navajo Generating Station was very important for the economy of the region. It provided many jobs and paid money for land leases and coal. The Kayenta Mine, which supplied coal to the plant, also depended entirely on the plant for its income. Together, the plant and mine paid about $100 million in wages and $50 million in leases and royalties each year.

Most of the owners of the plant did not want to keep it running past 2019. This was because making electricity from natural gas had become much cheaper across the country. The Navajo Nation asked the government to help keep the plant open to save jobs. This would have likely meant relaxing environmental rules or providing financial help.

Jobs and Payments

The Navajo Generating Station had 538 employees, paying about $52 million in wages each year.

The plant was built on 1,786 acres of land leased from the Navajo Nation. It also had agreements for the railroad and power lines that crossed tribal lands.

Annual lease payments to the Navajo Nation were about $608,000 in 2012. The plant also paid about $400,000 each year in air permit fees to the Navajo Nation EPA.

Property taxes paid to the State of Arizona were about $4.8 million per year. Since 2011, payments were also made to the Navajo Nation, which were about $2.4 million per year.

Lease Extension Talks

The plant owners and the Navajo Nation talked about extending the land lease for another 25 years after it ended in December 2019. Under the proposed new lease, payments would have increased to $9 million per year starting in 2020. There would also be extra payments that could go up to $34 million in 2020. These payments would have been adjusted for inflation. If the new lease had been approved, the plant could have operated until December 22, 2044. However, since the new lease was not approved, the plant closed.

Mine Jobs and Royalties

The Kayenta mine, which supplied coal to the plant, had 430 employees and paid about $47 million in wages each year.

The mine also paid royalties for the coal, which were about 12.5% of the sales. These royalties and other payments from the mine totaled about $50 million per year. Of this, $37 million went to the Navajo Nation and $13 million went to the Hopi tribe.

Impact on Local Economies

In 2012, payments from the Navajo Generating Station and the Kayenta Mine made up about a quarter of the Navajo Nation's income and 65% of the Hopi Tribe's income.

Most of the plant and mine employees were Native American tribal members, mainly Navajo. This meant about 850 direct jobs for tribal members.

The plant and mine also supported about 1,600 other jobs indirectly. If the plant had kept running with all three units, it was expected to create over 2,100 indirect jobs for the Navajo Nation alone by 2020.

The plant also had a big impact on the state of Arizona. It was expected to contribute $20 billion to the state's economy between 2011 and 2044 if it had continued running.

If the plant had to install the expensive new SCR equipment, the cost of water from the Central Arizona Project could have gone up by as much as 32% for farmers and Native American tribes. If the plant closed, those water rates were expected to increase by as much as 66%.

In 2012, the Navajo Generating Station and the Navajo Tribal Utility Authority (NTUA) worked together to bring electricity to 62 homes in the community of LeChee.

Water Use Agreement

The water used by the plant came from Arizona's share of the Colorado River water. The plant paid for this water. The payment rate was set to increase from $7 an acre-foot to $90 an acre-foot in 2014.

Electricity Production Over the Years

Here's how much electricity the Navajo Generating Station produced each year:

| Year | Gigawatt-hours (GW·h) |

|---|---|

| 2011 | 16,952 |

| 2012 | 15,888 |

| 2013 | 17,132 |

| 2014 | 17,297 |

| 2015 | 13,573 |

| 2016 | 12,059 |

| 2017 | 13,781 |

| 2018 | 13,017 |

See also

In Spanish: Navajo Generating Station para niños

In Spanish: Navajo Generating Station para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |