New Orleans Outfall Canals

New Orleans, Louisiana, has three important outfall canals: the 17th Street, Orleans Avenue, and London Avenue canals. These canals are a key part of the city's flood control system. They act like big drains, moving water out of much of New Orleans. About 13 miles (21 km) of levees and floodwalls run along the sides of these canals. The 17th Street Canal is the biggest and most vital. It can carry more water than the Orleans Avenue and London Avenue canals put together.

The 17th Street Canal stretches about 13,500 feet (4,100 m) north from Pump Station 6 to Lake Pontchartrain. It sits on the border of Orleans and Jefferson parishes. The Orleans Avenue Canal is between the 17th Street and London Avenue canals. It runs about 11,000 feet (3,400 m) from Pump Station 7 to Lake Pontchartrain. The London Avenue Canal goes about 15,000 feet (4,600 m) north from Pump Station 3 to Lake Pontchartrain. It is about halfway between the Orleans Avenue Canal and the Inner Harbor Navigation Canal.

Contents

How Hurricane Katrina Damaged the Canals

When Hurricane Katrina hit Louisiana and Mississippi on August 29, 2005, a huge storm surge from the Gulf of Mexico rushed into Lake Pontchartrain. The levees along the lake's south shore held up as they were supposed to. However, the floodwalls along the three outfall canals broke in several places.

The floodwall on the east bank of the 17th Street Canal broke south of the Old Hammond Highway Bridge. The London Avenue Canal had two big breaks. One was on the west side near Robert E. Lee Boulevard. The other was on the east side near Mirabeau Avenue. Luckily, the Orleans Avenue Canal's floodwalls did not break.

On September 1, 2005, helicopters started dropping sandbags into the 17th Street Canal breach. Metal sheets were also driven across the canal at the Old Hammond Highway Bridge. Sandbags and a sheet pile wall were also used to close the London Avenue Canal on September 3, 2005. Temporary pumps were brought in to remove the water and drain the city. The Orleans Metro area was officially dry by September 20, 2005. In total, the Corps of Engineers removed over 250 billion US gallons (950,000,000 m3) of water. They also replaced 2.3 miles (3.7 km) of floodwalls and 22.7 miles (36.5 km) of levees. They fixed 195.3 miles (314.3 km) of damage caused by the water.

Experts later found that engineers had guessed the soil strength was stronger than it actually was. This meant the soil under the levees was weaker during Hurricane Katrina than what was used in the design. A newer study confirmed this. It added that engineers made a mistake because they misunderstood a study from the 1980s. They thought sheet piles only needed to go 17 feet (5.2 m) deep. But they actually needed to go between 31 feet (9.4 m) and 46 feet (14 m) deep. This decision saved about $100 million but made the flood protection weaker.

The Orleans Avenue Canal did not break. It had an accidental spillway. This spillway helped release pressure and let water flow out of the canal.

In 2007, the United States Army Corps of Engineers studied the canals. They wanted to find the "safe water level" for the 2007 hurricane season. They looked at 4.8 miles (7.7 km) of walls and levees in 36 sections. They found that only two sections could hold more than 13 feet (4.0 m) of water. Many other sections could not hold more than 7 feet (2.1 m) of water.

How Water Moves in New Orleans

New Orleans sits between the Mississippi River to the south and Lake Pontchartrain to the north. It is about 100 miles (160 km) upstream from where the Mississippi River meets the ocean.

Over many years, people have changed how water moves in New Orleans. They did this to keep floodwaters out, remove water from inside the city, help boats move, and strengthen the land.

Building artificial levees was the biggest change. These levees were built on top of natural high ground. They stop the Mississippi River from overflowing. Later, levees were built along Lake Pontchartrain to stop floods from that side.

As canals were dug and more levees were built, the natural water flow areas were split into smaller ones. One of these is called "Orleans Metro." It includes the most crowded part of New Orleans. It is bordered by Lake Pontchartrain to the north and the Mississippi River to the south. It also includes famous neighborhoods like the French Quarter and Garden District.

Half of New Orleans is below sea level. So, the city uses special pumps to remove rainwater. The 17th Street, Orleans Avenue, and London Avenue outfall canals are the main ways water leaves the Orleans Metro area. During heavy rain, pumps operated by the Sewerage and Water Board of New Orleans move rainwater. They send it through a system of canals into the three outfall canals and then into Lake Pontchartrain.

History of the Outfall Canals

Early Canal Construction

New Orleans was founded in 1718 by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne. It was built on high ground next to the Mississippi River. The city had trouble draining rainwater because of the land's shape.

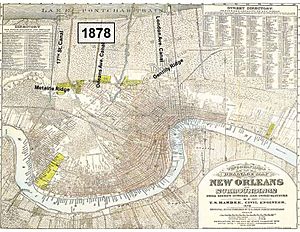

Two ridges, Metairie and Gentilly, are about 3 feet (0.91 m) to 4 feet (1.2 m) above sea level. They are between the Mississippi River and Lake Pontchartrain. These ridges made it hard for rainwater to flow north into Lake Pontchartrain. Bayou St. John, a natural waterway, was not enough to drain the heavy rainfall.

To help with drainage and flood protection, people built man-made canals by the mid-1800s. Drainage machines and pumps were built to lift water over the high ridges and into the outfall canals. By 1878, there were about 36 miles (58 km) of drainage canals. Today, there are 90 miles (140 km) of covered drainage canals and 82 miles (132 km) of open canals.

These early main drainage canals were the 17th Street, Orleans Avenue, and London Avenue canals. As the city grew north toward the lake, low-lying swamps were drained. This was done by digging shallow ditches that fed into the new canal system. However, draining the swamps caused the land to sink. This land subsidence continues today.

Building the outfall canals had another big effect. By digging through the Metairie and Gentilly ridges, the canals created paths for storm surges to enter New Orleans from Lake Pontchartrain.

The New Orleans Sewerage and Water Board started in 1899. It became the main group dealing with drainage problems. The Orleans Levee Board, a state agency, was formed in 1890. It helped maintain levees and floodwalls.

In 1915 and 1947, strong hurricanes hit New Orleans. They caused a lot of damage and killed many people. Water went over and broke the levees along the outfall canals. After these hurricanes, the Sewerage and Water Board and the Orleans Levee District raised the levees by about 3 feet (0.91 m). But some of these levees had sunk by as much as 10 feet (3.0 m) over nearly 100 years.

Federal Government Gets Involved

The federal government first got involved with hurricane protection in New Orleans in 1955. Congress asked the Secretary of the Army to study coastal areas where hurricanes had caused severe damage. This happened after several hurricanes in 1954. This first involvement only allowed a study, not any building.

As part of this study, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers looked at the Lake Pontchartrain and Vicinity area. This area includes most of St. Bernard Parish, parts of Orleans Parish, and parts of Jefferson and St. Charles parishes. This area is one large natural drainage basin.

After seven years of planning, the Corps released a report in 1962. It suggested a plan to prevent flooding in New Orleans from a "Standard Project Hurricane." This is a made-up hurricane that represents the worst possible storm for the area.

The plan suggested building a barrier at the east end of Lake Pontchartrain. This barrier would have locks to stop storm surges from entering the lake. It would also reduce salty water from the Gulf of Mexico entering the lake. The plan said the existing levees along the three outfall canals were good enough for hurricane protection.

Hurricane Betsy's Impact

In September 1965, Hurricane Betsy hit Louisiana near New Orleans. It caused huge damage and many deaths. Betsy was similar to the "Standard Project Hurricane." But its strong winds and waves made people question if the original levee and floodwall heights were high enough. As a result, the Corps was allowed to raise levee and floodwall heights by 1 foot (0.30 m) to 2 feet (0.61 m).

A report in 1968 also showed that the outfall canals needed to be fixed. Their levees were not high enough for new federal design rules after Hurricane Betsy. But no clear instructions were given on how to improve flood protection along the canals. This problem remained for over 20 years.

Congress approved the Barrier Plan after Hurricane Betsy. The federal government agreed to pay 70 percent of the building costs. The Corps thought the project would be done by the late 1970s.

However, local officials and groups opposed the Barrier Plan. Some worried it would hurt boat access to the lake. Others worried about flooding the north shore of Lake Pontchartrain when the barriers were closed. Environmental groups were also concerned about the barrier's effects on nature.

The Corps had to write an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) to explain the project's environmental effects. In 1975, an environmental group challenged the EIS in court. A judge stopped further work on the barrier plan until the Corps wrote a better EIS. The Corps decided not to continue with the barrier plan. In 1980, they found that building higher levees was cheaper, better for the environment, and more accepted locally.

In 1985, it was approved to increase levee heights along the lakefront. With this "High Level Plan," the Corps could now build hurricane and storm surge protection along the lakefront and outfall canals.

Choosing a Protection Plan for Canals

From the late 1970s, the Corps started looking at ways to protect the outfall canals. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Corps suggested building special gates at the Orleans Avenue and London Avenue canals. These "butterfly gates" would close if a storm surge threatened to enter the canals. (These gates did not include extra pumps like those added after Hurricane Katrina.)

For the 17th Street Canal, building butterfly gates cost about the same as building higher parallel levees. So, the Corps agreed to build "parallel protection" along that canal.

However, for the smaller London and Orleans Avenue Canals, the Corps preferred the gates-no-pumps plan. It was much cheaper. The parallel protection plan was estimated to cost three to five times more.

The Orleans Levee Board (OLB) and the Sewerage and Water Board wanted parallel protection for all canals. They believed that if the gates closed during a storm, water inside the city would not be able to drain into Lake Pontchartrain. Since interior drainage was not part of the federal hurricane protection plan, the OLB and Sewerage and Water Board would have to pay for any pumps needed. They argued that parallel protection would offer better storm surge protection and keep drainage working.

The Corps argued for the cheaper butterfly gates plan. They felt they had to choose the plan with the best cost-benefit. Cost was the main reason. There was nothing to show that the gates-only plan was better, only that it was less expensive.

For several years, the project was stuck. The local groups successfully asked Congress to make the Corps build the more expensive parallel protection plan for all three outfall canals. This happened in the Water Resources Development Act of 1990. Two years later, Congress said the federal government would pay 70 percent of the cost.

With the problem solved, the Corps began designing and building "I-wall"-type floodwalls on top of the levees. These I-walls helped raise the height of the banks in tight spaces without disturbing nearby homes. Construction started in 1993. Work along the outfall canals was almost finished in 2005, just before Hurricane Katrina.

New Closure Structures

After Hurricane Katrina, the Corps of Engineers worked quickly to repair the damage. But they knew they could not fix all the breaches before the 2006 hurricane season. So, they built temporary gated closure structures at the mouths of all three canals. These structures stop storm surges from entering the canals. The Corps also installed 34 temporary pumps near these structures to drain floodwaters.

These gates stay open during normal weather. When a storm surge threatens to raise the water level too high, the Corps closes the gates. Then, pumps move rainwater from the city into the outfall canals. Other pumps then move that water from the outfall canals, around the closed gates, and into Lake Pontchartrain. The closed gates protect the city from storm surge. Once the surge goes down, the gates reopen, and normal drainage starts again.

The Corps was allowed to build these temporary structures under emergency flood control laws passed in September 2005. It cost about $400 million to build them.

Later, the Corps received permission to build permanent gates and pumps. This new authority allowed them to build closure structures at the mouths of the outfall canals, even though earlier laws had prevented it. The total cost for this permanent project is about $804 million.

Since Hurricane Katrina, the Corps of Engineers has been building and strengthening 350 miles (560 km) of levees, floodwalls, barriers, and gates. This is part of the Greater New Orleans Hurricane and Storm Damage Risk Reduction System (HSDRRS). This system covers five parishes. When finished, the HSDRRS will protect against a "100-year storm." This is a storm that has a one percent chance of happening in any given year.

The temporary closure structures already provide this 100-year level of protection. The permanent canal closures and pumps will continue to provide the same level of safety. The contract for the permanent structures was given in 2011, and construction was completed in the fall of 2014.

Strengthening Canal Walls

Even though the new closure structures stop storm surges, parts of the outfall canal floodwalls are being strengthened. This is to meet stricter design rules made after Hurricane Katrina. Once this work is done, all canals will be able to handle a maximum water level of +8.0 NAVD 88. All strengthening work along the outfall canals was planned to happen within the existing areas and was scheduled to be finished by June 2011.