Nez Perce in Yellowstone Park facts for kids

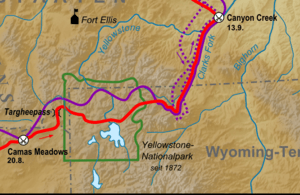

The Nez Perce in Yellowstone Park tells the story of the Nez Perce people's journey through Yellowstone National Park in 1877. This happened during the Nez Perce War, when the Nez Perce were trying to escape from the U.S. Army. From August 20 to September 7, 1877, they traveled through the park. During this time, they had some dangerous meetings with park visitors. The Army's chase eventually pushed the Nez Perce out of the Yellowstone Plateau and into an area where more soldiers were waiting for them near the Clark's Fork of the Yellowstone River.

Contents

Why the Nez Perce Traveled Through Yellowstone

In June 1877, several groups of the Nez Perce, about 750 people including men, women, and children, were trying to avoid being moved from their homes in Oregon to a reservation in Idaho. They wanted to escape east through Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming, crossing the Rocky Mountains to reach the Great Plains.

By late August, the Nez Perce had traveled hundreds of miles. They had fought several battles, often holding off or even defeating the U.S. Army. The Nez Perce hoped that after crossing each mountain range or winning a battle, they would find a peaceful new home.

News of the Nez Perce War was widely reported across the country. Many Americans saw their fighting retreat as amazing, and their leader, Chief Joseph, became known as a national hero. On August 9, 1877, the Nez Perce fought the U.S. Army, led by Colonel John Gibbon, at the Battle of the Big Hole in Montana. This battle was very tough for both sides, but the Nez Perce managed to escape south into Idaho. General Oliver Otis Howard's army was close behind, feeling embarrassed that they hadn't defeated the Nez Perce yet.

Entering Yellowstone Park

On August 20, 1877, the Nez Perce and the U.S. Army fought again at the Battle of Camas Creek in Idaho. The Nez Perce raided a soldier's camp, taking mules, horses, and supplies. The fight lasted all day but had few serious injuries. That evening, the Nez Perce headed east. They crossed Red Rock Pass and entered Yellowstone National Park and Wyoming on August 23, 1877.

General Howard's scouts, including Bannock scouts and Stanton G. Fisher, followed a day behind. They told Howard that the Nez Perce planned to cross the Yellowstone Plateau and head for the Crow agency on the Yellowstone River. Howard's soldiers were tired, so they rested for four days near Henrys Lake before continuing their chase on August 27.

Meanwhile, General William Tecumseh Sherman, Howard's boss, was setting up a trap for the Nez Perce. Lt. Gustavus Cheyney Doane and about 100 soldiers were sent to guard the north entrance of Yellowstone Park at Mammoth Hot Springs. Colonel Samuel D. Sturgis and 360 men were positioned at the Clark's Fork on the east. Major Hart, with 250 cavalry and 100 Indian scouts, was to guard the Shoshone River exit, also on the east. To the south, Colonel Wesley Merritt and 500 men were near the Wind River. And to the north, at Fort Keogh in Montana, Colonel Nelson A. Miles was ready with several hundred soldiers.

The Nez Perce had fewer than 200 fighting men against about 2,000 soldiers and many Indian scouts. Poker Joe, who was half-White and spoke English, guided them through Yellowstone. The Nez Perce leaders worked together, with Looking Glass being a very important war leader. Although Chief Joseph is often seen as the main leader, his role was more about managing the camp of women and children. The chiefs tried to stop their young men from harming White civilians, but they weren't always successful.

Meetings with Park Visitors

When the Nez Perce entered Yellowstone, there were about eight or nine groups of tourists, totaling at least 35 people, plus several groups of prospectors. Two of these tourist groups had dangerous encounters with the Nez Perce.

One group, known as the Radersburg Party, had nine tourists from Radersburg, Montana. They had been in the park for eight days by August 23, 1877. This group included George F. and Emma Cowan, Emma's brother and sister Frank and Ida Carpenter, Charles Mann, Henry Meyers, A.J. Arnold, William Dingee, and Albert Oldham. They were camped west of the Lower Geyser Basin. Just days before, General Sherman himself had been a tourist in the park. His scout had reportedly told the Radersburg party they would be safe from the Nez Perce. However, Emma Cowan noted that Sherman's group "preferred being elsewhere, as they left...that same night."

Another group of young men became known as the Helena party. On the evening of August 23, Andrew Weikert, Richard Dietrich, Charles Kenck, Frederick Pfister, Jack Stewart, Leonard Duncan, Joseph Roberts, August Foller, Leslie Wilke, and a cook named Benjamin Stone were camping at Yellowstone Falls. Not far from the Radersburg party were John Shively, a lone prospector, James Irwin, a recently discharged soldier, and "Texas Jack" (John Omohondro), a scout with a small group of English tourists.

The Radersburg Party Encounter

After entering the park, the Nez Perce moved along the Madison and Firehole Rivers to the Lower Geyser Basin. A small group of Nez Perce scouts, led by Yellow Wolf, went ahead. On the afternoon of August 23, Yellow Wolf's scouts captured John Shively at the meeting point of the East Fork of the Firehole River (now called Nez Perce Creek) and the Firehole River. They forced him to guide them through Yellowstone.

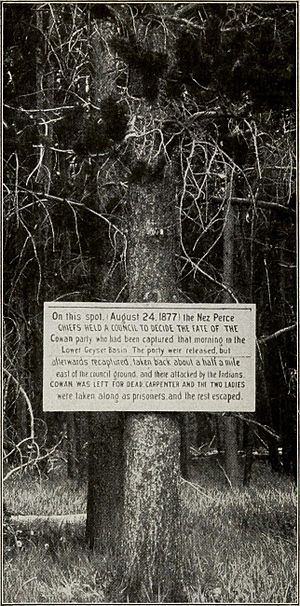

On the morning of August 24, Yellow Wolf's scouts rode into the Radersburg party's camp. They forced the group to come with them east toward the Yellowstone River to the main Nez Perce camp. By noon, the Nez Perce chiefs decided to let the party go, but only if they left all their supplies and horses. The tourists agreed and started heading west out of the park.

About 30 minutes later, they met a group of 20-30 Nez Perce who wanted to bring the tourists back to the chiefs. Shots were fired. George Cowan was shot, and Albert Oldham was wounded in the face. The rest of the group scattered into the forest. When a Nez Perce chief learned what happened, he helped some of the tourists. Frank Carpenter, Ida Carpenter, and Emma Cowan were brought back to the Nez Perce camp and protected by Chief Joseph.

On August 25, the Nez Perce continued east to Trout Creek on the Yellowstone River, in what is now Hayden Valley. By late afternoon, they had crossed the Yellowstone near Mud Volcano, at a place now called Nez Perce Ford. During the day, Nez Perce scouts found James Irwin hiding and brought him to their camp. On the evening of August 25, the Nez Perce released the Carpenters and Emma Cowan, giving them two horses. They safely went north and found protection from Lt. Doane's cavalry near Mount Washburn. James Irwin and John Shively stayed with the Nez Perce as guides. Over the next few days, other members of the Radersburg party left the park through the Madison River and found safety with General Howard's forces. On August 30, Howard's soldiers found George Cowan and Albert Oldham alive but in poor condition.

The Helena Party Encounter

Unfortunately for the Helena party, James Irwin had told the Nez Perce where their camp was located near Otter Creek. At dawn on August 26, a Nez Perce war party found the Helena party's camp. Two members, Weikert and Wilke, had already left. The Nez Perce attacked the camp with gunfire. Charles Kenck was killed. John Stewart was wounded in the leg and captured. The other members, including Richard Dietrich, ran into the forest. Stewart managed to buy his freedom from the Nez Perce with $263 and a silver watch. After cleaning his wounds, he headed north out of the park.

When Weikert and Wilke returned to their camp, they discovered the attack and immediately headed north. They also had a brief encounter with the Nez Perce war party, and Weikert was wounded in the shoulder. On August 27, the main Nez Perce force moved further east, away from the tourists and the army. Also on the 27th, Weikert, who had reached Mammoth Hot Springs, went south to look for Dietrich and the others. By the end of the day, Dietrich and Ben Stone were safe at McCartney's Hotel at Mammoth Hot Springs. James McCartney and Weikert agreed to go back to Otter Creek to find Kenck, Stewart, and the others.

The Burning of Henderson's Ranch

While Weikert and McCartney traveled south, a group of 20-30 Nez Perce were moving north toward Mammoth Hot Springs. These Indians had already burned Baronett's Bridge, the first bridge across the Yellowstone River. The Nez Perce found Dietrich and Stone and chased them into the forest, where they managed to escape.

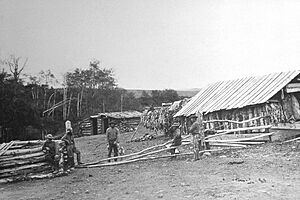

On the morning of August 31, the Nez Perce group moved north of the Gardner River and attacked the Henderson Ranch, a homestead established in 1871 just north of the park. A two-hour gunfight followed, but no one was injured. Sterling Henderson and his workers left the ranch for the safety of the river. The Nez Perce then looted and burned the buildings.

Soon after the attack, cavalry led by Lt. Doane moved up the river near Devil's Slide. They quickly fought the Nez Perce and pushed them back into the park. Unfortunately for Dietrich, he thought the Nez Perce had left the Mammoth Hot Springs area and took shelter in one of McCartney's buildings. As the Nez Perce fled south, they found Dietrich and killed him. Weikert and McCartney found Charles Kenck's body at Otter Creek and buried him. When they returned to Mammoth, they found Dietrich dead as well. Fearing for Ben Stone's safety, they went north to Lt. Doane's camp, where they found Ben Stone safe. Although there were a few other small fights between soldiers and the Nez Perce in the park, they caused only minor injuries.

The Nez Perce's Clever Escape

The Nez Perce entered Yellowstone National Park on August 23, 1877. On September 6, 1877, they left the park's northeast corner through Crandall Creek, heading toward the Clark's Fork of the Yellowstone. Inside the park, the Nez Perce knew of three ways to escape: northwest via the Yellowstone River, northeast via Clark's Fork, or east via the Shoshone River.

The Nez Perce suspected the Army would be waiting at all the usual exits. So, they chose a difficult and less-known route over the Absaroka Mountains, reaching heights of nearly 10,000 feet (3,048 meters). Fisher, who was following them, said it was "the roughest country I ever undertook to pass through." After a small fight with the Nez Perce's rear guard, Fisher turned back to find General Howard.

Once the main Nez Perce group left the Yellowstone River, they moved up Pelican Creek onto the Mirror Plateau. It was here that James Irwin escaped. James Shively escaped a few days later. The Nez Perce continued east, crossing the Lamar River and climbing one of the major creeks. They reached the mountain divide on the evening of September 5, 1877. On the morning of September 6, they continued northeast down Crandall Creek and into the canyon of the Clark's Fork of the Yellowstone. Although Howard's forces were never far from the Nez Perce, Howard never fought them in the park and chose an easier route to the Clark's Fork.

The Army's Trap and the Nez Perce's Trick

Howard and his soldiers crossed Yellowstone using an easier northern route. They reached the northeast corner of the park on Clark's Fork on September 7. From Fisher's scouting reports, the Army knew the Nez Perce would come out of the mountains near the Clark's Fork or Shoshone Rivers. Howard continued down the Clark's Fork River, hoping to trap the Nez Perce between his army and Sturgis's soldiers waiting below.

To prevent the army from learning their location during their difficult journey down from the Absaroka mountains, the Nez Perce hunted down and killed White prospectors and hunters in the area. Ten men were known to have been killed by the Nez Perce, and more bodies were found in the following months.

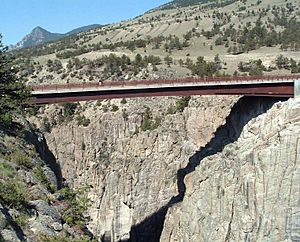

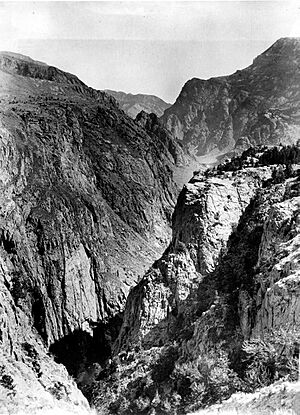

Other army troops meant to guard the Yellowstone exits were not yet in place. So, Sturgis set up his base on the plains, where he had a wide view and could move quickly toward either Clark's Fork or the Shoshone River. He seemed to think the Clark's Fork exit was impossible, saying "no trail could possibly lead through it." The lower part of Clark's Fork went through a narrow canyon with vertical walls 800 feet (244 meters) high.

On September 8, the Nez Perce reached a ridge near what is now called Dead Indian Pass, about six miles (9.7 km) from Sturgis's soldiers. Their scouts saw the soldiers far below. If the Nez Perce took the easy, open route to the plains, their 2,000 horses and 700 people would be easily seen. Instead, they tried a clever trick to mislead the soldiers. They took a route going south toward the Shoshone River. Then, hidden from army scouts, they rode their horses in a big circle to hide their tracks. This made it look like they were heading south.

Then, they secretly went back north, hidden by thick trees. They traveled through Dead Indian Gulch down to the Clark's Fork River. Dead Indian Gulch was a narrow, steep crack in the rock, dropping almost vertically for 1,000 feet (305 meters) and barely wide enough for two horses side-by-side. A military historian said, "In a cleanly executed maneuver, the Nez Perce had countered an extremely serious threat and won a brilliant, though temporary respite."

Sturgis fell for the trick and led his soldiers away from the Clark's Fork, heading south to the Shoshone. The Nez Perce then passed onto the plains without anyone stopping them. Sturgis quickly realized his mistake and turned around. He met Howard on September 11, who had followed the Nez Perce's route down the Clark's Fork. But now, the two army forces were two days and 50 miles (80 km) behind the Nez Perce.

What Happened Next

Howard ordered Sturgis to chase the Nez Perce, whose trail led north into Montana. Sturgis caught up with them on September 13 at the Battle of Canyon Creek, which didn't have a clear winner. Colonel Miles later accepted Chief Joseph's surrender in the Bears Paw Mountains on October 5, 1877, just a few miles from the Canada–US border.

George Cowan and Albert Oldham fully recovered from their injuries. Cowan later spent a lot of time in the park, telling visitors about his experience with the Nez Perce. Weikert and McCartney eventually found the bodies of Kenck and Dietrich, and both are buried in Helena, Montana.

In 1902, Major Hiram M. Chittenden, a U.S. Army engineer and Yellowstone's main road builder, started a project to mark all the historic spots in the park from the 1877 Nez Perce war. By 1904, with help from people like George and Emma Cowan, signs marked the places of all the important encounters. However, by the 1930s, all the signs were gone. Today, the only memorial is "The Chief Joseph Story" roadside marker where Nez Perce Creek crosses the Grand Loop Road.

Part of the Nez Perce's route is now followed by Wyoming Highway 296, which is called the Chief Joseph Scenic Byway. Sunlight Creek Bridge, Dead Indian Hill, and Dead Indian Campground are along the approximate path the Nez Perce took before they tricked the soldiers on the plains below.

Park Features Named After the Event

- Nez Perce Creek (known as the East Fork of the Firehole River in 1877). It was officially named Nez Perce Creek in 1885 during the Arnold Hague Geological Surveys of the park.

- Nez Perce Ford is where Chief Joseph and his people crossed the Yellowstone River on August 25, 1877. It was first named by superintendent Philetus Norris in 1880.

- Joseph Peak is a mountain in the Gallatin Range. It was named by members of the Arnold Hague survey in 1885 to honor Chief Joseph's journey through the park.

- Cowan Creek is a small stream that flows into Nez Perce Creek. It was named in honor of George F. Cowan, who was wounded by the Nez Perce near the creek's mouth. Chief Park Naturalist David Condon officially named the creek in 1956.

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |