Nichiren facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Nichiren日蓮 |

|

|---|---|

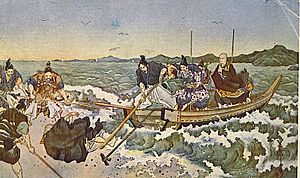

A 15th century portrait of Nichiren. From Kuon-ji Temple in Mount Minobu, Yamanashi prefecture.

|

|

| Religion | Buddhism |

| Denomination | Nichiren Buddhism |

| School |

|

| Lineage |

|

| Education | Kiyozumi-dera Temple (Seichō-ji), Enryaku-ji Temple on Mount Hiei |

| Other names |

|

| Dharma names |

|

| Personal | |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Born | 16 February 1222 Kominato village, Awa province, Japan |

| Died | 13 October 1282 (aged 60) Ikegami Daibo Hongyoji Temple, Musashi province, Japan |

| Religious career | |

| Teacher | Dōzenbo of Seichō-ji Temple |

Nichiren (born February 16, 1222 – died October 13, 1282) was an important Japanese Buddhist priest and philosopher during the Kamakura period in Japan. He believed that the Lotus Sutra held the most important Buddhist teachings for his time. He taught that people should only follow this teaching and spread it widely.

Nichiren encouraged people to chant the phrase Nam(u)-myoho-renge-kyo. He said this was the only way to reach Buddhahood, which means becoming enlightened like a Buddha. He believed that even Shakyamuni Buddha and other Buddhist figures were special examples of a Buddha-nature that everyone has inside them. He also taught that followers of the Lotus Sutra should share its message, even if they faced difficulties.

Nichiren wrote many letters and essays, which help us understand his life and ideas. After he passed away, he was given special titles like "Great Bodhisattva Nichiren" and "Great Teacher of Correction" by emperors. Today, many different groups follow Nichiren's teachings, including traditional temples and lay movements. They all have slightly different ways of understanding his ideas.

Contents

Nichiren's Life Story

Nichiren's life story comes mostly from his own writings. He wrote many letters and essays, with one collection having over 500 complete works. The first detailed biography about him, not from a religious group, appeared more than 200 years after he died.

He started sharing his teachings in 1253. He believed that the Lotus Sutra was the most important teaching, based on older Tendai Buddhist ideas. In 1260, he wrote an important paper called Risshō Ankoku Ron. In this paper, he said that a country that follows the Lotus Sutra would have peace. But if rulers supported other religious teachings, it would lead to trouble and disaster.

Nichiren also wrote in 1264 that chanting "Nam(u)-myoho-renge-kyo" included all Buddhist teachings and could lead to enlightenment. Because of his strong beliefs, he faced serious challenges from the government of the Kamakura shogunate. These difficulties made him feel like he was "reading the Lotus Sutra with his body," meaning he was living out its teachings through his struggles.

In 1274, Nichiren's predictions of foreign invasion and political problems seemed to come true. This happened with the first Mongol invasion attempt and a coup within the Hōjō clan. Because of this, the government pardoned him and asked for his advice, but they didn't follow it. His paper, Risshō Ankoku Ron, is now seen as an important historical document that shows the worries of that time.

Nichiren is still a talked-about figure among scholars. Some see him as a strong nationalist, while others see him as a social reformer with a global religious vision. He is often compared to other religious leaders who tried to bring about change in their societies.

His Birth and Early Life

Nichiren was born on February 16, 1222, in a village called Kominato, which is now part of Kamogawa in Chiba Prefecture. There are different stories about his family background. Nichiren himself said he was "the son of lowly people living on a rocky strand of the out-of-the-way sea." This was different from other famous Buddhist leaders of his time, who usually came from noble or samurai families in the Kyoto area.

Even though Nichiren was proud of his humble beginnings, some of his followers later tried to say he came from a more important family. This might have been to attract more people to his teachings. His father was Mikuni-no-Tayu Shigetada, and his mother was Umegiku-nyo. When he was born, his parents named him Zennichimaro, which means "Splendid Sun" or "Virtuous Sun Boy." The exact place where he was born is believed to be underwater near a temple that celebrates his birth.

His Buddhist Education

From 1233 to 1253, Nichiren deeply studied all ten types of Buddhism popular in Japan at that time. He also studied Chinese classics and other writings. During these years, he became sure that the Lotus Sutra was the most important teaching. In 1253, he returned to the temple where he first studied to share what he had learned.

He began his Buddhist studies at age 12 at a Tendai temple called Seichō-ji. At 16, he became a monk and took the name Renchō, meaning "Lotus Growth." He then traveled to Kamakura to study Pure Land Buddhism, which focused on chanting the name of Amitābha Buddha. He also studied Zen Buddhism, which was becoming popular.

Next, he went to Mount Hiei, the main center for Japanese Tendai Buddhism. There, he carefully examined the original Tendai teachings and how they had mixed with Pure Land and Esoteric Buddhism. Finally, he visited Mount Kōya, a center for Shingon Buddhism, and Nara, where he studied its six main schools, especially the Ritsu sect, which focused on strict rules for monks.

Declaring the Lotus Sutra

On April 28, 1253, Nichiren returned to Seicho-ji Temple. He gave a lecture about his 20 years of study. On that same day, he publicly declared Nam(u) Myoho Renge Kyo from Mount Kiyosumi. This was the start of his mission to bring Tendai Buddhism back to focusing only on the Lotus Sutra. He also began trying to convert all of Japan to this belief.

At this event, Nichiren changed his name to Nichiren. This name combines Nichi (meaning "Sun," symbolizing truth and Japan) and Ren (meaning "Lotus," for the Lotus Sutra). Nichiren believed Japan was the country where the true Buddhist teaching would be reborn and spread worldwide.

During his lecture, Nichiren strongly criticized Hōnen, the founder of Pure Land Buddhism, and its practice of chanting Nam(u) Amida Butsu. He likely also spoke against the teachings at Seicho-ji that had included other ideas. This made the local leader, Hojo Kagenobu, angry, and he tried to have Nichiren killed. Modern studies suggest these events happened over a longer time and had social and political reasons.

Nichiren then set up his base in Kamakura. He converted several Tendai priests and attracted followers, mostly from the lower and middle samurai classes. These followers supported him financially and formed the core of Nichiren communities in the Kantō region of Japan.

First Warning to the Government

Nichiren arrived in Kamakura in 1254. Between 1254 and 1260, many people died due to a series of disasters like droughts, earthquakes, diseases, and fires. Nichiren looked for answers in Buddhist scriptures to explain these problems. He wrote that these sufferings were due to people's weakened spiritual state. He believed this caused the Kami (protective spirits) to abandon the nation. He argued that the main reason for this was the widespread adoption of Pure Land teachings.

His most famous work from this time was the Risshō Ankoku Ron, which means "On Securing the Peace of the Land through the Propagation of True Buddhism." Nichiren gave this paper to Hōjō Tokiyori, the real leader of the Kamakura shogunate. He hoped it would lead to big changes. In it, he said that the ruler needed to accept the "correct form of Buddhism" (the Lotus Sutra) to bring peace and wealth to the land and end suffering.

The paper was written as a dialogue between a wise Buddhist man (Nichiren) and a visitor. They discuss the nation's problems, and the wise man slowly convinces the visitor to embrace the Lotus Sutra's ideas. Nichiren used stories and examples to make his points clear.

He supported his arguments by quoting from many Buddhist scriptures. He argued that if the ruler did not stop supporting other Buddhist schools, it would lead to more disasters, civil war, and foreign invasion.

Nichiren submitted his paper on July 16, 1260, but the government didn't respond officially. However, it caused a strong reaction from priests of other Buddhist schools. Nichiren was challenged to a debate, which he claimed to have won easily. But his opponents' followers tried to kill him at his home, forcing him to flee Kamakura. His critics had influence with government officials and spread false rumors about him. One year after he submitted the Rissho Ankoku Ron, he was arrested and sent away to the Izu peninsula.

Nichiren's exile to Izu lasted two years. During this time, he began to focus on chapters 10-22 of the Lotus Sutra. He started to emphasize that the purpose of human life is to practice the bodhisattva ideal in the real world, which means facing struggles and showing endurance. He saw himself as an example of this, a "votary" (follower) of the Lotus Sutra.

After being pardoned in 1263, Nichiren returned to Kamakura. In November 1264, he was attacked and almost killed in Awa Province. For the next few years, he preached outside Kamakura but returned in 1268. At this time, the Mongols sent messages to Japan, demanding tribute and threatening invasion. Nichiren sent 11 letters to important leaders, reminding them of his predictions in the Rissho Ankoku Ron.

Facing Execution

The threat of Mongol invasion was a huge crisis for Japan. In 1269, Mongol messengers again demanded that Japan surrender. The government prepared its military defenses.

Buddhism had long been used for "nation-protection" in Japan, and the government asked Buddhist schools for prayers. Nichiren and his followers felt that his predictions of foreign invasion were coming true, and more people joined his movement. Nichiren wrote to his followers that he was giving his life to fulfill the Lotus Sutra. He increased his criticisms against the non-Lotus teachings that the government supported, even as the government tried to unite the nation.

His actions made powerful religious figures and their followers angry, especially the Shingon priest Ryōkan. In September 1271, after a heated exchange of letters, Nichiren was arrested by soldiers. He was tried by Hei no Saemon, a high-ranking official. Nichiren saw this as his second warning to the government.

According to Nichiren, he was sentenced to exile but was taken to Tatsunokuchi beach for execution. At the last moment, a bright light appeared in the sky, scaring his executioners and saving his life. Some scholars have different ideas about what happened.

Regardless, Nichiren's life was spared, and he was sent away to Sado Island. This event is called the "Tatsunokuchi Persecution." Nichiren saw it as a turning point, like a death and rebirth. In Nichiren Buddhism, this is called his moment of Hosshaku kenpon, meaning "casting off the temporary and revealing the true."

Second Exile

After the failed execution, Nichiren was exiled to Sado Island in the Sea of Japan. He was sent to a small, rundown temple in a graveyard. Nichiren and a few disciples faced harsh cold, little food, and threats from local people during their first winter.

Scholars notice a change in Nichiren's writings from before his Sado exile compared to during and after. At first, he was worried about his followers in Kamakura. The government tried to stop the Nichiren community by exiling people, putting them in prison, taking their land, or removing them from their families. Many of his disciples seemed to lose faith, and others wondered why they and Nichiren faced such problems when the Lotus Sutra promised "peace and security."

In response, Nichiren began to see himself like Sadāparibhūta, a key figure in the Lotus Sutra who faced many challenges while spreading the sutra. Nichiren argued that these hardships proved the Lotus Sutra's truth. He also saw himself as the bodhisattva Visistacaritra, to whom Shakyamuni entrusted the future of the Lotus Sutra. He believed he was leading a large group of Bodhisattvas of the Earth who would help those who were suffering.

He wrote many letters and papers on Sado, including two of his most important works: Kanjin no Honzon Shō ("The Object of Devotion for Observing the Mind") and Kaimoku Shō ("On the Opening of the Eyes"). In "On the Opening of the Eyes," he wrote that facing difficulties should be expected. He said that continuing his mission to spread the sutra was more important than being protected. He ended this work by vowing to be the "pillar of Japan, the eyes of Japan, the great ship of Japan."

The Mandala Gohonzon

By the end of the winter of 1271–1272, Nichiren's situation had improved. He gained a few followers on Sado who helped him, and disciples from the mainland started visiting with supplies. In 1272, there was an attempted coup in Kamakura and Kyoto, which seemed to fulfill his prediction of rebellion. At this point, Nichiren was moved to much better living conditions.

While on Sado Island, Nichiren created the first Mandala Gohonzon. This was a calligraphic drawing of the assembly at Eagle Peak, meant to be used as an object of devotion or worship. He wrote on it: "This is the great mandala never before revealed in Jambudvipa during the more than 2,200 years since the Buddha's nirvana." He created many more Mandala Gohonzon throughout his life. Over a hundred of these, written by Nichiren himself, still exist today.

Return to Kamakura

Nichiren was pardoned on February 14, 1274, and returned to Kamakura a month later, on March 26. He wrote that his innocence and the accuracy of his predictions led the regent Hōjō Tokimune to help him. Scholars suggest that some of his well-connected followers might have influenced the government's decision to release him.

On April 8, he was called by Hei no Saemon, who asked about the timing of the next Mongol invasion. Nichiren predicted it would happen within the year. He used this meeting as another chance to warn the government. He urged the government to rely only on the Lotus Sutra, saying that prayers based on other rituals would bring more disaster.

Deeply disappointed that the government didn't listen, Nichiren left Kamakura on May 12, planning to live alone. However, five days later, he visited Lord Hakii Sanenaga of Mt. Minobu. There, he learned that his followers in nearby areas had remained strong during his exile. Despite bad weather and hardships, Nichiren stayed in Minobu for the rest of his life.

Retirement to Mount Minobu

During his time at Mount Minobu, Nichiren led a large group of followers in the Kantō region and on Sado mainly through his many letters. During the "Atsuhara affair" in 1279, when the government attacked Nichiren's followers instead of him, his letters show him as a strong and well-informed leader. He gave detailed instructions through a network of disciples who connected Minobu with other affected areas in Japan. He also helped his followers understand what was happening.

More than half of Nichiren's existing letters were written during his years at Minobu. Some were touching letters to followers, thanking them, giving advice on personal matters, and explaining his teachings simply. Two of his works from this period, Senji Shō ("The Selection of the Time") and Hōon Shō ("On Repaying Debts of Gratitude"), are considered among his five major writings.

At Minobu, Nichiren also increased his criticisms of mystical practices that had been added to the Japanese Tendai school. It became clear that he was creating his own form of Lotus Buddhism.

Nichiren and his disciples finished the Myō-hōkke-in Kuon-ji Temple in 1281. This building later burned down and was replaced by a new one.

While at Minobu, Nichiren also created many Mandala Gohonzon for specific disciples and lay believers. Some of these Gohonzon were very large, possibly for use in chapels by his followers.

His Passing

In 1282, after years of living quietly, Nichiren became ill. His followers encouraged him to visit hot springs for their healing benefits and to go to land offered by Hagiri Sanenaga for recovery. On his way, he stopped at a disciple's home in Ikegami, outside present-day Tokyo. He passed away there on October 13, 1282.

Legend says he died surrounded by his disciples. He had spent several days lecturing on the Lotus Sutra from his sickbed, writing a final letter, and giving instructions for the future of his movement. He also named six senior disciples. His funeral and cremation happened the next day.

His disciples left Ikegami with Nichiren's ashes on October 21 and returned to Minobu on October 25.

- Nichiren Shu groups say his tomb is at Kuon-ji on Mount Minobu, as he requested, and his ashes remain there.

- Nichiren Shoshu claims that Nikko Shonin later took his ashes and other items to Mount Fuji. They say these are now kept next to the Dai Gohonzon within the Hoando storage house.

Nichiren's Teachings

Nichiren's teachings changed and grew throughout his life. We can see this by studying his writings and the notes he made in his personal copy of the Lotus Sutra.

Some scholars divide his teachings into different periods, such as before and during his exile, and during his years at Minobu.

Nichiren focused on making his teachings last. He summarized his main ideas: Buddhahood is eternal, and everyone can achieve it in their lives. He believed his mission was to help people realize their enlightenment. His followers who share his goal are the Bodhisattvas of the Earth. This means followers should have a spiritual and moral unity based on their shared Buddha-nature. Nichiren started this community, and his future followers must spread it globally. This is Nichiren's vision of Kosen-rufu, a time when the Lotus Sutra's teachings would be widely known around the world.

Nichiren set an example for Buddhist social action long before it became common in other Buddhist schools. His teachings were unique because he tried to make Buddhism practical and real. He strongly believed that his teachings would help a nation become better and eventually lead to world peace.

Some of his religious ideas came from the Tendai understanding of the Lotus Sutra and other beliefs common in his time. But other ideas were completely new and unique to him.

Ideas from Tendai or Other Schools

Nichiren lived in his time, and some of his teachings came from existing ideas or new ones in Kamakura Buddhism. Nichiren took these ideas and made them his own.

Finding the Buddha Land Here and Now

Nichiren emphasized that the Buddha's pure land can be found in this world, not just in a faraway place. This idea, called immanence, means that enlightenment can be achieved in one's current life. The belief that enlightenment is not something you gain, but something you already have inside you, had been taught before. These ideas were based on the concept of "Three Thousand Realms in a Single Moment of Life," which says that the universe is connected.

Nichiren took these ideas further by saying they could actually be achieved, not just thought about. He taught that cause and effect happen at the same time. He said that focusing on one's mind happens when you truly believe in and commit to the Lotus Sutra. According to Nichiren, these things happen when a person chants the title of the Lotus Sutra and shares its truth with others, even if it means facing danger.

Nichiren created a three-part relationship: faith, practice, and study. Faith meant accepting his new way of understanding the Lotus Sutra. It was something that needed to grow deeper all the time. He explained that "to accept [faith in the sutra] is easy," but "to uphold it is difficult." He said that becoming a Buddha comes from upholding faith. This could only be done by chanting the daimoku (the title of the Lotus Sutra) and teaching others to do the same, along with studying.

Because of this, Nichiren strongly disagreed with the Pure Land school, which focused on hoping for a pure land after death. He believed that when a person connects with their inner Buddha-nature, their current world becomes peaceful. For Nichiren, spreading the Lotus Sutra widely and achieving world peace was possible and bound to happen. He gave his future followers the job of making it happen.

The Latter Day of the Law

The Kamakura period in 13th-century Japan felt like a time of great worry. Nichiren, like others then, believed they were in the Latter Day of the Law. This was a time that Shakyamuni Buddha predicted his teachings would lose their power. Japan was indeed facing many natural disasters, internal conflicts, and political problems.

Nichiren believed that the troubles and disasters were caused by the widespread practice of what he called "inferior" Buddhist teachings, which the government supported. However, he was very positive about this time. He said that, unlike other Mahayana schools, this was the best possible time to be alive. It was the era when the Lotus Sutra would spread, and the Bodhisattvas of the Earth would appear to share it. He even said, "It is better to be a leper who chants Nam(u)-myōhō-renge-kyō than be a chief abbot of the Tendai school."

Debates and Strong Arguments

The tradition of having open debates to clarify Buddhist principles was common in many Asian countries, including Japan.

During the Kamakura period, there were many lively religious discussions. Temples competed for support from wealthy and powerful people through sermons. Preachers tried to attract crowds. Preaching spread from temples to homes and streets, as traveling monks shared their ideas with everyone, educated or not. They used storytelling, music, and drama to teach, which later led to Noh theater.

A big topic of debate was "slander of the Dharma," which means speaking badly about Buddhist teachings. The Lotus Sutra itself warns strongly against this. Hōnen, a Buddhist leader, used strong words, telling people to "discard," "close," "put aside," and "abandon" the Lotus Sutra and other teachings that were not Pure Land. Many people, including Nichiren, strongly criticized his ideas.

However, Nichiren made countering "slander of the Dharma" a main part of Buddhist practice. Many of his writings focus on explaining what the true essence of Buddhist teachings is, rather than just how to meditate.

At age 32, Nichiren began to criticize other Buddhist schools of his time. He declared what he believed was the correct teaching, the Universal Dharma (Nam(u)-Myōhō-Renge-Kyō). He said chanting these words was the only way for both individuals and society to find peace. His first target was Pure Land Buddhism, which was becoming popular. Nichiren's detailed reasons are best explained in his Risshō Ankoku Ron, his first major paper and the first of his three warnings to the government.

Even though his times were harsh, Nichiren always chose the power of words over violence. He was direct and always sought discussion, whether through debates or letters. He once said, "Whatever obstacles I may encounter, as long as men [persons] of wisdom do not prove my teachings to be false, I will never yield."

"Single Practice" Buddhism

Hōnen introduced the idea of "single practice" Buddhism. He taught that people should focus on just one practice: chanting the name of Amida Buddha. This was a new idea because it was simple and available to everyone, and it reduced the power of the monastic system.

Nichiren adopted the idea of a single, easy-to-access practice. But instead of chanting Amida's name, he taught chanting the daimoku of Nam(u)-myōhō-renge-kyō. This meant giving up the idea of hoping for a Pure Land after death. Instead, it focused on achieving Buddhahood in one's current life, as taught in the Lotus Sutra.

Protective Forces

Japan had a long history of folk beliefs that existed alongside Buddhist schools. Many of these beliefs influenced different religious groups, a process called syncretism. These beliefs included the idea of kami, which are native gods, goddesses, or protective forces that influence events in the world. Some believed kami were connected to the Buddha. The belief in kami was very strong at the time. People believed that through prayers and rituals, they could call upon kami to protect the nation.

According to some accounts, Nichiren studied Buddhism mainly to understand why the kami seemed to have abandoned Japan, as seen in the decline of the imperial court. He concluded that because the court and people had turned to teachings that weakened their minds, both wise people and protective forces had left the nation.

He argued that through proper prayer and action, his troubled society could become an ideal world of peace and wisdom. He said that "the wind will not thrash the branches nor the rain fall hard enough to break clods."

Unique Teachings

Nichiren's writings also contain several unique Buddhist ideas.

The Five Guides for Spreading Teachings

Developed during his Izu exile, the Five Guides are five ways to judge and rank Buddhist teachings. They are: the quality of the teaching, the natural ability of the people, the time, the characteristics of the land or country, and the order of how the Dharma is spread. Using these five ideas, Nichiren declared his understanding of the Lotus Sutra to be the best teaching.

The Four Denunciations

Throughout his life, Nichiren strongly criticized Buddhist practices other than his own, as well as the existing social and political system. He used a method called shakubuku, which means converting people by strongly challenging their beliefs. He would shock his opponents with his criticisms while attracting followers with his great confidence. Some modern critics say his "single-truth" view was intolerant. Others argue that his words should be understood in the context of his samurai society, not through modern ideas of tolerance.

As he continued his work, Nichiren's strong criticisms against Pure Land teachings grew to include sharp criticisms of the Shingon, Zen, and Ritsu schools of Buddhism. Together, these criticisms are known as "the Four Denunciations." Later, he criticized the Japanese Tendai school for using Shingon elements. He said that relying on Shingon rituals was like magic and would harm the nation. He believed Zen was wrong for thinking enlightenment was possible without relying on the Buddha's words. He called Ritsu "thievery" because it hid behind small good deeds. In simple terms, the Four Denunciations criticized ideas that made people feel hopeless or encouraged them to escape from reality.

The Three Great Secret Laws

Nichiren believed the world was in a time of decline and that people needed a simple and effective way to rediscover the core of Buddhism. He described his Three Great Secret Laws as this very way.

In a writing called Sandai Hiho Sho, Nichiren explained three teachings from the 16th chapter of the Lotus Sutra. He said these were secret because he received them as the leader of the Bodhisattvas of the Earth through a silent message from Shakyamuni. They are: the chanting (daimoku), the object of worship (honzon), and the place of worship (kaidan).

The daimoku, which is the rhythmic chanting of Nam(u)-myōhō-renge-kyō, is the way to discover that your own life, the lives of others, and the world around you are the essence of the Buddha. This chanting is done while looking at the honzon. At age 51, Nichiren created his own Mandala Gohonzon, which is a drawing that represents the universe. Chanting daimoku to it is Nichiren's way of meditating to experience the truth of Buddhism. He believed this practice was powerful, easy to do, and right for the people and the time.

Nichiren described the first two secret laws in many writings. But the idea of the "platform of ordination" (place of worship) appears only in the Sandai Hiho Sho, a work whose true origin has been questioned by some scholars. Nichiren seemed to leave the full meaning of this secret Dharma to his followers. Its meaning has been debated. Some say it means building a physical national place of worship approved by the emperor. Others believe the place of worship is the community of believers or simply where followers of the Lotus Sutra live and work together to create peace in the land. This last idea means that religion and daily life are strongly connected, and everyone works together to create a perfect society.

According to Nichiren, practicing the Three Secret Laws leads to "Three Proofs" that show their truth. The first is "documentary proof," meaning if the religion's main texts (Nichiren's writings) clearly show the religion's importance. "Theoretical proof" is whether the teachings logically explain life and death. "Actual proof," which Nichiren thought was most important, shows the truth of the teaching through real improvements in practitioners' daily lives.

Changing Karma to Mission

Nichiren understood the struggles his followers faced every day. He assured them they could "cross the sea of suffering." He taught that by overcoming challenges, they would gain inner freedom, peace of mind, and understanding of the Dharma, no matter what happened in life. He accepted the common Buddhist idea that a person's current situation was the result of past thoughts, words, and actions. However, he didn't focus much on blaming current problems on past deeds. Instead, he saw karma through the Lotus Sutra's teachings, which could help all people become Buddhas, even those who seemed ignorant or bad in the Latter Day of the Law.

When facing difficult situations, chanting Nam(u)-myoho-renge-kyo would open the wisdom of the Buddha. This would change karma into a mission and a joyful way of life. Beyond one person's life, this process would awaken a person's care for society and sense of social responsibility.

Nichiren used the term "votary of the Lotus Sutra" to describe himself. The Lotus Sutra itself talks about the great difficulties that people who follow and spread its teachings will face. Nichiren said he "read the sutra with his body," meaning he willingly faced the predicted hardships instead of just reciting or thinking about the words.

By facing these challenges, Nichiren claimed to have found his personal mission. He felt great joy even during his harsh exile. In his mind, his sufferings became chances to change his karma and give his life a higher meaning.

In letters to some of his followers, Nichiren extended the idea of facing difficulties for the sake of spreading the Dharma to include everyday problems like family disagreements or illness. He encouraged these followers to take responsibility for such life events. He told them to see these as chances to repay past karmic debts and lessen their impact more quickly.

Nichiren reached a strong belief that offered a new way to see karma. He said that his determination to carry out his mission was most important. The Lotus Sutra's promise of a peaceful life meant finding joy in overcoming karma.

The Great Vow for Kosen-rufu

Nichiren's teachings are full of vows he made for himself and asked his followers to share. Some were personal, like often telling people to change their inner lives. He urged his followers to gain "treasures of the heart" and to think about how they behaved. These vows were about this world, not just ideas, and came with an easy-to-do practice.

Nichiren also made a "great vow" with a political side. He and his future followers would create the conditions for a fair nation and world, which the Lotus Sutra calls Kosen-rufu. In earlier Japanese Buddhism, "nation" meant imperial rule, and "peace of the land" meant the government's stability. However, Nichiren's teachings fully embraced a new idea in medieval Japan: that "nation" referred to the land and its people. Nichiren was unique in charging the actual government with the peace of the land and the flourishing of the Dharma. In his teachings, all human beings are equal, whether a ruler or an ordinary person. Enlightenment is not just for an individual's inner life but is achieved by working to transform the land and create an ideal society.

This means there is an urgent task. Nichiren connected the great vow of people in the Lotus Sutra to raise everyone to the Buddha's awareness. He linked this to his own struggles to teach the Law despite great challenges. He also linked it to his command for future disciples to create the Buddha land in this world for many years to come.

Nichiren and His Followers

Nichiren was a strong leader who attracted many followers during his travels and exiles. Most of these followers were warriors and feudal lords. He told his women followers that they could also achieve enlightenment. He set a high standard for leadership and shared his reasons and plans with them in his writings. He openly encouraged them to share his beliefs and struggles.

He left the fulfillment of the kaidan, the third of his Three Secret Dharmas, to his disciples. His many existing letters show how deep and wide his relationships with them were, and what he expected from them. They trusted his leadership and his understanding of Buddhism. Many asked for his advice to solve personal problems. Many actively supported him financially and protected his community. Several disciples were praised by him for sharing his hardships, and a few lost their lives in these situations. Even though the movement he started faced divisions over the centuries, his followers kept his teachings and example alive. Today, his followers are found in important lay movements and traditional Nichiren schools.

The relationship between Nichiren and his disciples is called shitei funi, meaning the oneness of mentor and disciple. Even though the roles of mentor and disciple might be different, they share the same goals and responsibilities. Nichiren said that this "oneness" is a main theme of the Lotus Sutra, especially in chapters 21 and 22, where the Buddha entrusts the future of the sutra to the gathered bodhisattvas.

After Nichiren's Death

After Nichiren passed away, his teachings were understood in different ways. Because of this, Nichiren Buddhism now includes several main branches and schools. Each has its own beliefs and ways of interpreting Nichiren's teachings.

Nichiren's Writings

Many of Nichiren's writings still exist in his own handwriting, some complete and some as fragments. Other documents are copies made by his first disciples. In total, over 700 of Nichiren's works still exist. These include written lectures, letters of warning, and drawings.

Scholars have divided Nichiren's writings into three groups: those everyone agrees he wrote, those generally believed to be written by others after his death, and a third group where the truthfulness is still debated.

Besides formal writings in Classical Chinese, Nichiren also wrote explanations and letters to followers in a mix of Japanese characters and simpler writing. He also wrote letters in simplified Japanese for believers like children who couldn't read the more formal styles. Some of his formal works, especially the Risshō Ankoku Ron, are considered excellent examples of that writing style. Many of his letters show great care and understanding for the common people of his time.

Important Writings

Among his formal writings, five are generally accepted by Nichiren schools as his most important works:

- On Securing the Peace of the Land through the Propagation of True Buddhism (Rissho Ankoku Ron) — written between 1258 and 1260.

- The Opening of the Eyes (Kaimoku-sho) — written in 1272.

- The True Object of Worship (Kanjin-no Honzon-sho) — written in 1273.

- The Selection of the Time (Senji-sho) — written in 1275.

- On Repaying Debts of Gratitude (Ho'on-sho) — written in 1276.

Nichiren Shōshū adds five more writings to make a set of ten major works. Other Nichiren groups disagree with these choices, saying they are less important or not truly written by him.

Personal Letters to Followers

Among his existing writings are many letters to his followers. These include thank-you notes, messages of sympathy, answers to questions, and spiritual advice for difficult times in their lives. These letters show that Nichiren was very good at comforting and challenging people in ways that fit their unique personalities and situations.

Many of these letters use stories from Indian, Chinese, and Japanese traditions, as well as historical tales and stories from Buddhist scriptures. Nichiren included hundreds of these stories and sometimes added his own details. Some of the stories he told don't appear in other collections and might be original.

Another type of his letters follows the style of Japanese zuihitsu, which are lyrical and loosely organized essays that mix personal thoughts and poetic language. Nichiren was a master of this style. These informal works show his very personal and strong way of teaching, as well as his deep care for his followers.

Nichiren used his letters to inspire important supporters. About one hundred followers are named as recipients, and several received between 5 and 20 letters. The people who received letters were often from the warrior class. There are only a few mentions of his lower-status followers, many of whom could not read. The letters he wrote to his followers during the "Atsuhara affair" in 1279 show how he used personal written messages to guide their response to the government's actions and keep them strong during the difficult time.

Writings to Women

In a time when earlier Buddhist teachings often said women could not achieve enlightenment, or only after death, Nichiren was very supportive of women. Based on different parts of the Lotus Sutra, Nichiren stated that "Other sutras are written for men only. This sutra is for everyone."

Ninety of his existing letters, almost one-fifth of the total, were sent to women. Nichiren Shu has published separate books of these writings.

In these letters, Nichiren often praised women for their detailed questions about Buddhism. He also encouraged them in their efforts to achieve enlightenment in this lifetime. He paid special attention to the story of the Dragon King's daughter in the Lotus Sutra, who achieved enlightenment instantly. He also showed deep concern for the fears and worries of his female disciples.

Sword Connected to Nichiren

The "Juzumaru-Tsunetsugu" is a katana sword linked to Nichiren. This sword was given to Nichiren by a follower, Nanbu Sanenaga, for protection. Nichiren did not use the sword. Instead, he held it as a symbol for "destroying evil and establishing what is right." He placed a juzu rosary on its handle, which gave the sword its name.

The 13th-century sword maker Aoe Tsunetsugu is said to have made the Juzumaru-Tsunetsugu. However, research shows that the Juzumaru looks different from other confirmed swords made by Aoe Tsunetsugu. For example, the artist's signature on the Juzumaru is on the opposite side of where Aoe would usually sign his swords. There is still debate about who truly made the sword.

English Translations of Nichiren's Writings

- The Major Writings of Nichiren. Soka Gakkai, Tokyo, 1999.

- Heisei Shimpen Dai-Nichiren Gosho (平成新編 大日蓮御書: "Heisei new compilation of Nichiren's writings"), Taisekiji, 1994.

- The Writings of Nichiren, Volume I, Burton Watson and the Gosho Translation Committee. Soka Gakkai, 2006, ISBN: 4-412-01024-4.

- The Writings of Nichiren, Volume II, Burton Watson and the Gosho Translation Committee. Soka Gakkai, 2006, ISBN: 4-412-01350-2.

- The Record of the Orally Transmitted Teachings, Burton Watson, trans. Soka Gakkai, 2005, ISBN: 4-412-01286-7.

- Writings of Nichiren, Chicago, Middleway Press, 2013, The Opening of the Eyes.

- Writings of Nichiren, Doctrine 1, University of Hawai'i Press, 2003, ISBN: 0-8248-2733-3.

- Writings of Nichiren, Doctrine 2, University of Hawai'i Press, 2002, ISBN: 0-8248-2551-9.

- Writings of Nichiren, Doctrine 3, University of Hawai'i Press, 2004, ISBN: 0-8248-2931-X.

- Writings of Nichiren, Doctrine 4, University of Hawai'i Press, 2007, ISBN: 0-8248-3180-2.

- Writings of Nichiren, Doctrine 5, University of Hawai'i Press, 2008, ISBN: 0-8248-3301-5.

- Writings of Nichiren, Doctrine 6, University of Hawai'i Press, 2010, ISBN: 0-8248-3455-0.

- Letters of Nichiren, Burton Watson et al., trans.; Philip B. Yampolsky, ed. Columbia University Press, 1996 ISBN: 0-231-10384-0.

- Selected Writings of Nichiren, Burton Watson et al., trans.; Philip B. Yampolsky, ed. Columbia University, Press, 1990,ISBN: 0-231-07260-0.

See also

In Spanish: Nichiren para niños

In Spanish: Nichiren para niños

- Nichiren, a 1979 Japanese film starring Kinnosuke Yorozuya as Nichiren.

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |