Niger-Congo languages facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Niger–Congo |

|

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution: |

Africa |

| Linguistic classification: | Proposed language family |

| Proto-language: | Proto-Niger–Congo language |

| Subdivisions: |

Dogon?

Mande?

Ijoid?

Lafofa? (Kordofanian?)

Kru?

Siamou?

Atlantic–Congo? (noun classes)

|

| ISO 639-2 and 639-5: | nic |

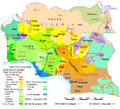

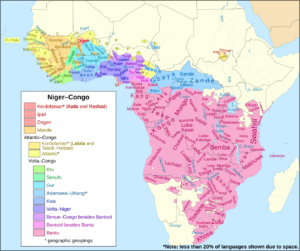

Map showing the distribution of major Niger–Congo languages. Pink-red is the Bantu subfamily.

|

|

The Niger–Congo language family is a huge group of languages spoken across most of sub-Saharan Africa. It includes the Mande languages, the Atlantic–Congo languages, and possibly other smaller language groups.

If this family is proven to be true, it would be the world's largest in terms of how many languages it has. It would also be the third-largest by the number of people who speak these languages. In Africa, it covers the biggest area. Ethnologue lists 1,540 different Niger–Congo languages.

About 700 million people spoke Niger–Congo languages in 2015. This makes it the third-largest language family in the world by native speakers. The Bantu languages alone are spoken by 350 million people. This is half of all Niger–Congo speakers!

Some of the most widely spoken Niger–Congo languages are Yoruba, Igbo, Fula, Lingala, Ewe, Fon, Ga-Dangme, Shona, Sesotho, Xhosa, Zulu, Akan, and Mooré. The most spoken language overall is Swahili. Many people in eastern and southeastern Africa use Swahili to communicate.

Linguists generally agree that the main part of Niger–Congo, called Atlantic–Congo, comes from a single origin. However, how the different branches within it are related is still being studied. Some other main branches might include Dogon, Mande, Ijo, Katla, and Rashad. The link for Mande languages, especially, has not been fully shown. Without them, the idea of Niger–Congo as one big family is still debated.

One special feature of Atlantic–Congo languages is their noun-class system. This is like a gender system, but with many more categories.

Contents

Where Did Niger–Congo Languages Begin?

This language family likely started in or near West or Central Africa. This is where these languages were spoken before the Bantu expansion. Their spread might be connected to how farming grew in the Sahel region during the African Neolithic period. This happened after the Sahara Desert became drier around 3500 BCE.

Most experts on Niger–Congo languages believe they all came from a common origin. This is because they share similar noun-class systems, verb endings, and basic words. Linguists like Diedrich Westermann (in 1922) and Joseph Greenberg (in the 1960s) helped classify these languages. Greenberg's work became the starting point for how languages in Africa are grouped today.

However, linguists still debate how the languages within this family are divided. This makes it harder to pinpoint exactly where the family started. No complete "Proto-Niger–Congo" dictionary or grammar has been created yet.

One puzzle is the relationship between Niger–Congo and the Kordofanian languages. These are spoken in the Nuba mountains of Sudan. This area is not connected to where most Niger–Congo languages are spoken. Most linguists think Kordofanian languages are part of the Niger–Congo family. It's unclear if this group of speakers moved there or if the language family once covered a larger area.

There is more agreement about where the Benue–Congo family began. This is the largest subgroup. The Bantu languages within Benue–Congo are known to have started expanding around 1000 BCE. Linguist Roger Blench (2004) suggests that Benue–Congo likely began where the Benue and Niger Rivers meet in central Nigeria.

The classification of the Ubangian languages (found in the Central African Republic) as part of Niger–Congo is also debated. Greenberg included them, but some later experts have questioned this.

The Bantu expansion began around 1000 BC. It spread across much of Central and Southern Africa. This led to many local Pygmy and Bushmen (Khoisan) groups either joining the Bantu speakers or their languages dying out.

Main Language Groups

Here is a look at the language groups usually included in Niger–Congo. The exact family tree for some of these groups is still being studied.

The main part of the Niger–Congo group is the Atlantic–Congo languages. Other Niger–Congo languages that are not part of Atlantic–Congo include Dogon, Mande, Ijoid (which includes Ijaw and Defaka), Katla, and Rashad.

Atlantic–Congo Languages

- Further information: Atlantic–Congo languages and Languages of Nigeria

Atlantic–Congo combines the Atlantic languages and Volta–Congo. It includes over 80% of all Niger–Congo speakers. That's close to 600 million people in 2015.

The proposed Savannas group includes Adamawa, Ubangian, and Gur. Outside of the Savannas group, Volta–Congo includes Kru, Kwa, Volta–Niger, and Benue–Congo. Volta–Niger has two of the biggest languages of Nigeria: Yoruba and Igbo. Benue–Congo includes the Southern Bantoid group. This group is mostly made up of the Bantu languages, which are spoken by 350 million people.

Some linguists, like Roger Blench (2012), believe that some of these subgroups, such as Adamawa, Ubangian, Kwa, Bantoid, and Bantu, might not be single, unified groups.

Even though the Kordofanian branch is usually included in Niger–Congo, some researchers disagree. Glottolog (2019) does not agree that the Kordofanian branches (like Lafofa, Talodi, and Heiban) are Atlantic–Congo languages. It also considers Ijoid, Mande, and Dogon to be separate language families.

The Atlantic–Congo group is known for its noun class systems.

- Atlantic

The Atlantic group has about 35 million speakers (2016). Most of these are Fula and Wolof speakers. However, Atlantic is not considered a single, valid group.

- Senegambian languages: This group includes Wolof (spoken in Senegal) and Fula (spoken across the Sahel).

- Bak languages: Sometimes grouped with Senegambian.

- Mel languages

- Limba language

- Gola language

- Volta–Congo

- North-Volta

- Kru: Languages of the Kru people in West Africa. This group includes Bété, Nyabwa, and Dida.

- Adamawa-Ubangi:

- Adamawa: Nearly 100 languages and dialects. They are spoken across the Adamawa Plateau by about 1.6 million people (1996). The largest is Mumuye.

- Ubangian: A group of smaller languages in the Central African Republic. It might be a separate family or grouped with Adamawa.

- Gur: About 70 languages spoken in the Sahel and Savanna regions of West Africa. Around 20 million people spoke them in 2010. The largest is Mooré, with over 12 million speakers. Gur and Adamawa-Ubangi are sometimes grouped as Savannas languages.

- Senufo: Languages of the Senufo people (about 3 million speakers in 2010). They are spoken in Ivory Coast and Mali, with one group in Ghana. This group includes Senari and Supyire. Senufo was traditionally part of Gur but is now often seen as an early branch off Atlantic–Congo.

- South-Volta

- Kwa: A group of languages whose exact relationships are unclear. They are spoken along the Ivory Coast, southern Ghana, and central Togo. About 40 million people spoke them in the 2010s. The largest is Akan in Ghana, with about 22 million speakers (2014).

- Volta–Niger (also called "West Benue–Congo"): A large group of West African languages. They have about 110–120 million speakers.

- Gbe: Spoken in Ghana, Togo, Benin, and Nigeria. Ewe is the largest and best known, with 7 million speakers (2017).

- "YEAI": A large group of languages mainly in Nigeria, with about 100 million speakers.

- "NOI":

- Nupoid: About 3 million speakers (1990 estimates).

- Oko: A small group of related dialects in Kogi State.

- Idomoid: Languages of central Nigeria, including Idoma with 1 to 2 million speakers.

- Ayere-Ahan (nearly extinct or already extinct).

- Benue–Congo (East Benue–Congo)

- Bantoid-Cross:

- Cross River

- Northern Bantoid:

- Bantoid-Cross:

*Dakoid? *Fam? *Tikar? *Mambiloid

-

-

-

- Bendi

- Southern Bantoid: This group includes the widespread Bantu languages. They spread across Sub-Saharan Africa during the Bantu expansion (from about 1000 BCE to 500 CE).

-

-

*Tivoid-Beboid: A large number of languages in southwestern Cameroon and southeastern Nigeria. *Ekoid-Mbe *Mamfe *Grassfields *Jarawan-Mbam '*'Bantu: Divided into many groups, with 250 to 550 named languages.

-

-

- Central Nigerian (Platoid): Jukunoid, Kainji, Plateau.

- Other languages not yet fully classified within Benue–Congo: Ukaan, Fali of Baissa, Tita.

-

Other Niger–Congo Languages

The other proposed Niger–Congo languages are found in different areas. These include the upper Senegal and Niger river basins (south and west of Timbuktu), the Niger Delta, and far to the east in south-central Sudan (around the Nuba Mountains). These groups have about 100 million speakers in total (2015), mostly Mandé and Ijaw.

- Dogon: Languages of the Dogon people of Mali. About 1.6 million speakers (2013). They might have a noun-class system similar to Atlantic–Congo languages.

- Ijoid: Includes Ijaw (languages of the Ijaw people, 3 million speakers in 2011) and the nearly extinct Defaka language.

- Mande: Languages of the Mandé peoples, estimated at 70 million speakers (2016).

- Bangime: Spoken in Dogon country but seems unrelated to Dogon.

- Siamou: Once classified as Kru.

"Kordofanian" Languages

The various Kordofanian languages are spoken in south-central Sudan, near the Nuba Mountains. "Kordofanian" is a name for languages in a certain area, not a single language family. These are smaller languages, with about 100,000 speakers (1980s estimates). The Katla and Rashad languages show some similarities with Benue–Congo.

- Talodi languages

- Heiban languages

- Lafofa languages

- Rashad languages

- Katla languages

The endangered or extinct languages Laal, Mpre, and Jalaa are often thought to be part of Niger–Congo.

How Linguists Classified These Languages

Early Ideas

Linguists slowly realized that Niger–Congo was one big language family. In the past, they often grouped African languages based on whether they used prefixes to classify nouns. Sigismund Wilhelm Koelle (1854) made an important early classification. He noticed that Atlantic languages used prefixes, just like many languages in Southern Africa. This idea was also supported by Wilhelm Bleek (1856). Later, Carl Meinhof firmly established Bantu as a single language group.

Some early classifications mixed language types with ideas about race. For example, Friedrich Müller (1876–88) separated 'Negro' and Bantu languages.

Over time, linguists saw a connection between Bantu and other languages that had similar, but less complete, noun class systems. Some thought these languages were still developing into "full" Bantu languages. Others believed they had lost some of their original Bantu features.

Westermann and Greenberg's Contributions

Westermann studied the 'Sudanic languages'. In 1911, he divided them into 'East' and 'West' groups. By 1935, he clearly showed the relationship between Bantu and 'West Sudanic'.

Joseph Greenberg built on Westermann's work. Between 1949 and 1954, he argued that Westermann's 'West Sudanic' and Bantu were part of one family, which he called Niger–Congo. He also said that Bantu was a subgroup of the Benue–Congo branch. He added Adamawa-Eastern and said that Fula belonged to the West Atlantic languages. In his 1963 book, The Languages of Africa, he added Kordofanian as another branch. He then renamed the whole family Congo-Kordofanian, later called Niger–Kordofanian. Greenberg's ideas, though questioned at first, became widely accepted by scholars.

Later, Bennet and Sterk (1977) reclassified the family using a method called lexicostatistics. This led to the grouping used in Bendor-Samuel (1989). Kordofanian was then seen as one of several main branches, not a separate family. This brought back the name Niger–Congo. Many classifications still place Kordofanian as the most different branch. This is mainly because it shares fewer words with the others. Mande is often thought to be the second most different branch because it doesn't have the noun-class system typical of Niger–Congo. Dogon and Ijaw also lack this system.

Linguists are still working to prove Greenberg's Niger–Congo idea fully. Most research has focused on smaller language families within Niger–Congo. Reconstructing the "parent" language for the whole family is a big challenge.

However, studies using computer methods, like Grollemund, et al. (2016), support the idea that Niger–Congo is a single language family.

Reconstructing the Original Language

Linguists try to reconstruct "Proto–Niger–Congo," the original language from which all Niger–Congo languages came. This is like trying to figure out what the very first words sounded like. So far, a full dictionary of Proto–Niger–Congo has not been created. However, linguist Konstantin Pozdniakov (2018) has reconstructed the number system of this ancient language.

Niger–Congo and Nilo-Saharan Languages

Some linguists have suggested a link between Niger–Congo and Nilo-Saharan languages. This idea was first proposed by Westermann. Gregersen (1972) suggested combining them into a larger group called Kongo-Saharan. Roger Blench (1995) also supported this idea. However, Blench later changed his mind (2011). He suggested that the noun-classifier system in Central Sudanic (a Nilo-Saharan group) might have influenced the noun-class system in Atlantic–Congo languages. He thought similarities in words might be due to languages borrowing from each other.

Sounds (Phonology)

Niger–Congo languages often prefer open syllables, like CV (Consonant Vowel). The typical word structure of the original Proto–Niger–Congo language is thought to have been CVCV. This structure is still seen in Bantu, Mande, and Ijoid languages. Verbs usually have a root followed by endings. Nouns originally had a noun class prefix before the root.

Consonants

Many Niger–Congo languages have two types of consonants. They are often described as "strong" (fortis) and "weak" (lenis) consonants.

Vowels

Many Niger–Congo languages use "vowel harmony." This means that vowels in a word change to match each other. This is often based on the position of the tongue root (called [ATR]). In its most complete form, this system has two groups of five vowels each.

| [+ATR] (Tongue root forward) | [−ATR] (Tongue root back) |

|---|---|

| [i] | [ɪ] |

| [e] | [ɛ] |

| [ə] | [a] |

| [o] | [ɔ] |

| [u] | [ʊ] |

Words are usually either [+ATR] or [−ATR]. If a word has a [+ATR] vowel, then other vowels in the word, including endings, will also become [+ATR]. For example, in Wolof, suffixes change to match the root's [ATR] value.

Some vowels are "neutral" or "opaque." Neutral vowels don't change, but the vowels after them still follow the root's [ATR] value. Opaque vowels also don't change, but they make all the vowels after them match the opaque vowel's [ATR] value instead of the root's.

Some Niger–Congo languages have ten vowels, but seven- or nine-vowel systems are more common. In these systems, some vowels, like /a/, don't participate in vowel harmony.

Nasality

Some Niger–Congo languages have both oral (spoken through the mouth) and nasal vowels (spoken through the nose and mouth). In some languages, nasal consonants (like 'm' or 'n') might have developed from nasal vowels. Interestingly, some Niger–Congo languages might not have any nasal consonants at all.

Tone

Most Niger–Congo languages use tones. This means the pitch of your voice changes the meaning of a word. A typical system has two or three different pitch levels. Four-level systems are less common, and five-level systems are rare. Only a few Niger–Congo languages, like Swahili, do not use tones. The original Proto–Niger–Congo language is thought to have had two tone levels.

| Tones | Languages |

|---|---|

| High, Low | Dyula-Bambara, Maninka, Temne, Dogon, Dagbani, Gbaya, Efik, Lingala |

| High, Mid, Low | Yakuba, Nafaanra, Kasem, Banda, Yoruba, Jukun, Dangme, Yukuben, Akan, Anyi, Ewe, Igbo |

| Top, High, Mid, Low | Gban, Wobe, Munzombo, Igede, Mambila, Fon |

| Top, High, Mid, Low, Bottom | Ashuku (Benue–Congo), Dan-Santa (Mande) |

| Pitch-accent or stress | Mandinka (Senegambia), Fula, Wolof, Kimwani |

| none | Swahili |

Grammar (Morphosyntax)

Noun Classification

Niger–Congo languages are famous for their noun classification systems. These systems are found in almost every branch of the family, except for Mande, Ijoid, Dogon, and some Kordofanian branches. Noun classes are similar to grammatical gender in other languages, but there are often many more classes (10 or more!). These classes can be based on things like whether something is human, alive, or even abstract ideas or groups of objects. For example, in Swahili, the language is called Kiswahili, but the people are Waswahili.

In Bantu languages, where noun classification is very detailed, it usually appears as prefixes. Verbs and adjectives also change to match the class of the noun they refer to. For example, in Swahili, watu wazuri wataenda means 'good (zuri) people (tu) will go (ta-enda)'.

Verbal Extensions

The same Atlantic–Congo languages that have noun classes also have special endings for verbs. These endings can change the meaning of the verb. For example, in Swahili, penda means 'to love'. Adding -na makes it pendana, meaning 'to love each other'.

Word Order

Most Niger–Congo languages today use a Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) word order (like "I eat apples"). However, some branches like Mande, Ijoid, and Dogon use Subject-Object-Verb (SOV) word order (like "I apples eat"). Because of this, linguists have debated what the original word order of Proto–Niger–Congo was.

In most Niger–Congo languages, the noun comes first in a phrase. Adjectives, numbers, and possessive words usually come after the noun. For example, "house big" instead of "big house." However, in the western areas where verbs come last, possessive words might come before the noun.

The languages in the Mende region that put the verb at the end have some unusual word order rules. Even though verbs come after their direct objects, phrases like "in the house" usually come after the verb.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Lenguas nigerocongolesas para niños

In Spanish: Lenguas nigerocongolesas para niños

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |