Akan languages facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Akan |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ákán | ||||

| Native to | Ghana | |||

| Ethnicity | Akan | |||

| Native speakers | Ghana: 10.5 million, 9.0 million (2010)

Côte d'Ivoire: 569 thousand,346 thousand (2017)

Togo: 70 thousand

(2014)

(date missing) |

|||

| Language family |

Niger–Congo

|

|||

| Dialects |

Agona

Ahafo

Akyem Bosome

Asen

Denkyira

Fante

Kwawu

|

|||

| Writing system | Latin | |||

| Official status | ||||

| Official language in | None. — Government-sponsored language of Ghana |

|||

| Regulated by | Akan Orthography Committee | |||

|

||||

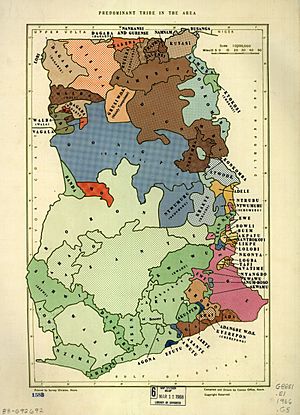

Akan is a group of languages that are very similar to each other. They are the main languages spoken by the Akan people in Ghana. You can hear Akan languages spoken across most of southern Ghana. About 80% of people in Ghana can speak an Akan language. Also, about 44% of Ghanaians speak Akan as their first language. These languages are also spoken in parts of Côte d'Ivoire.

Four main types of Akan have been developed for writing. These are Asante, Akuapem, Bono (all three are known as Twi), and Fante. Even though people speaking these different types can understand each other, it was hard for them to read each other's written forms. This changed in 1978 when the Akan Orthography Committee (AOC) created a common way to write Akan. This new writing system is mostly based on Akuapem Twi. Today, this shared writing system is used to teach in primary schools for speakers of other similar languages too.

During the time of the Atlantic slave trade, Akan languages traveled to the Caribbean and South America. For example, people in Suriname (like the Ndyuka) and Jamaica (like the Jamaican Maroons, also called the Coromantee) still speak parts of Akan. The cultures of people whose ancestors were enslaved and escaped in Suriname and Jamaica still show Akan influences. One example is the Akan tradition of naming children after the day of the week they were born. For instance, a boy born on a Sunday might be named Akwasi or Kwasi, and a girl might be named Akosua. In Jamaica and Suriname, the famous Anansi spider stories are still very popular.

Contents

History of the Akan Language

The Akan people living in Ghana moved there in different groups between the 11th and 18th centuries. Other Akan speakers live in eastern Côte d'Ivoire and parts of Togo. They moved from the north to the forest and coastal areas in the south around the 13th century.

The Akan people have a strong tradition of sharing their history through spoken stories. They are also famous in the art world for their special wooden, metal, and clay artworks. Their cultural ideas are shown in their stories and wise sayings (proverbs). They also use special designs in carvings and on clothes. Because of their rich culture and history, the Akan people in Ghana are studied by many experts. These include people who study stories, languages, human societies, and history.

How Akan Words Change

Akan words can change their form, especially when going from singular (one) to plural (more than one).

Making Nouns Plural

Some Akan nouns become plural by adding 'm' or 'n' to the beginning of the word. They also remove the first sound of the original word.

- For example, abofra (child) becomes mmofra (children). Here, 'ab' is removed, and 'mm' is added.

- Other examples include aboa (animal) becoming mmoa (animals), and abusua (family) becoming mmusua (families).

- Nouns that use the 'n' prefix include adaka (box) which becomes nnaka (boxes).

- Adanko (rabbit) becomes nnanko (rabbits), and aduro (medicine) becomes nnuro (medicines).

Another way to make nouns plural in Akan is by adding the ending nom to the word.

- For instance, agya (father) becomes agyanom (fathers).

- Nana (grandparent or grandchild) becomes nananom (grandparents or grandchildren).

- Nua (sibling) becomes nuanom (siblings).

Some Akan nouns stay the same whether they are singular or plural.

- Words like nkyene (salt), ani (eye), and sika (money) are written the same for both one or many.

Akan Literature

The Akan languages have many interesting stories, wise sayings (proverbs), and traditional plays. There are also new plays, short stories, and novels written in Akan. People started writing down this literature in the late 1800s.

Later, a famous person named Joseph Hanson Kwabena Nketia collected many proverbs and folktales. Some of his well-known works include Funeral Dirges of the Akan People (1969) and Folk Songs of Ghana (1963). Important writers in the Akan language include A. A. Opoku (who wrote plays) and K. E. Owusu (who wrote novels). Unfortunately, the Bureau of Ghana Languages has not been able to print new novels in Akan, so some older books are no longer available.

Education in Akan

Primary School

In 1978, the Akan Orthography Committee created a common way to write Akan. This writing system is now used to teach students in primary school. Akan is recognized as a language for learning to read and write, especially in the early primary grades (grades 1-3).

University Studies

Akan languages are taught at several big universities in the United States. These include Ohio University, Ohio State University, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Harvard University, Boston University, Indiana University, University of Michigan, and The University of Florida. Akan is often part of the Summer Cooperative African Languages Institute (SCALI) program. Students can study Akan in these universities to earn a bachelor's or master's degree.

Common Phrases in Akan

- Akwaaba – Welcome

- Aane (Twi) - Yes

- Nyew (Fante)– Yes

- Yiw (Akuapem) – Yes

- Yoo – Okay/Alright

- Oho / anhã (Fante)/Daabi (Twi)– No/Nope

- Da yie (Twi) – Good night (meaning "sleep well")

- Me rekɔ da(Fante) – I'm going to sleep

- Ɛte sɛn? (Twi) – How is it going?/How are you? (can also mean "hello")

- Medaase – Thank you

- Mepa wo kyɛw – Please/excuse me/I beg your pardon

- Ndwom (Fante)/nnwom (Twi) – Song/songs or music

- Wo din de sɛn?/Yɛfrɛ wo sɛn? (Twi) - What is your name?

- Wo dzin dze dεn? (Fante) – What is your name?

- Me dzin dze.../Wɔfrɛ me... (Fante) – My name is.../I'm called...

- Woedzi mfe ahen? (Fante) – How old is he/she?

- Edzi mfe ahen (Fante) – How old are you?

- ɔwɔ hen? – Where is it?

- Me rekɔ – I am going/ I am taking my leave.

- Mbo (Fante)/Mmo (Twi)– Good

- Jo (Fante)/Kɔ (Twi) – Leave

- Ayɛ Adze (Fante) – well done

- Gyae – Stop

- Da – Sleep

- Bra - Come

- Bra ha - Come here

- Bɛ didi - Come and eat

Names of Places

- Fie - Home

- Sukuu - School

- Asɔre - Church

- Dwaaso - Market

- sukuupon - University or a college

- Ayaresabea - Hospital

See also

In Spanish: Lenguas akánicas para niños

In Spanish: Lenguas akánicas para niños

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |