Operation Hush facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Operation Hush |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of The First World War | |||||||

The Yser front in 1917 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Douglas Haig Henry Rawlinson Sir Reginald Bacon John Philip Du Cane |

Friedrich Bertram Sixt von Armin Ludwig von Schröder |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5 divisions | 3 marine divisions, 1 army division | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| None | None | ||||||

Operation Hush was a secret British plan during World War I. It aimed to land soldiers from ships onto the Belgian coast in 1917. This attack would be supported by troops pushing forward from Nieuwpoort and the Yser river area. These positions were left over from the Battle of the Yser in 1914.

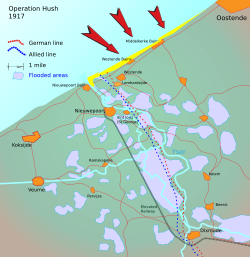

Several plans for this operation were thought about in 1915 and 1916. But they were put aside because of other battles happening elsewhere. Operation Hush was supposed to start when the main attack at Ypres, called the Third Battle of Ypres, had moved far enough inland. This would link up with advances by French and Belgian armies.

The Germans launched their own surprise attack on July 10, 1917. They called it Unternehmen Strandfest (Operation Beach Party). They used mustard gas for the first time. This attack captured part of the British area near the Yser river. It also destroyed two British soldier groups. After being delayed many times, Operation Hush was finally cancelled on October 14, 1917. The main attack at Ypres had not reached its goals, so the coastal landing could not begin.

In April 1918, British ships from the Dover Patrol attacked Zeebrugge. They tried to sink ships in the canal entrance to trap German U-boats. This closed the canal for a short time. Later, from September to October 1918, the Allies took back the Belgian coast during the Fifth Battle of Ypres.

Contents

Planning the Attack

Why the Coast was Important

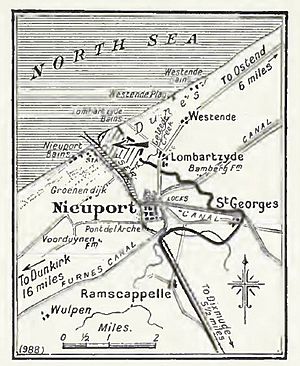

When Germany took over the Belgian coast in 1914, the British navy wanted them out quickly. In October 1914, Winston Churchill, a top navy leader, told John French, the British army commander, "We must have him off the Belgian coast." Churchill offered naval support for an army attack. French liked the idea for 1915. The army would move forward between Dixmude and the sea. The navy would bombard the coast and make a surprise landing near Zeebrugge.

However, the British government cancelled this plan. They decided to focus on the Gallipoli Campaign instead. In early 1916, the idea of a coastal attack came back. Talks began between Sir Douglas Haig, the new British army commander, and Rear Admiral Reginald Bacon, who led the Dover Patrol. Haig chose Lieutenant-General Aylmer Hunter-Weston to work with Bacon on the plan.

Admiral Bacon suggested landing 9,000 men in Ostend harbour. They would use six special warships called monitors and 100 fishing boats. Other ships would pretend to attack Zeebrugge and Middelkirke. This would happen as a land attack started from Nieuwpoort.

Hunter-Weston did not like this plan. He felt it was too narrow an attack. Ostend harbour was within range of German heavy guns. Also, the harbour exits could be easily blocked. Bacon then started working on a new plan for a beach landing near Middelkirke. This new plan included Hunter-Weston's ideas and Haig's wish to use tanks in the landings.

The Battle of the Somme in 1916 forced Haig to delay any attacks in Flanders until 1917. The coastal attack depended on holding the Yser river area. This river was deep, wide, and affected by tides. A planning group decided that the operation should not start until the main attack from Ypres had reached Roulers. Haig agreed with this.

New Ways to Land Troops

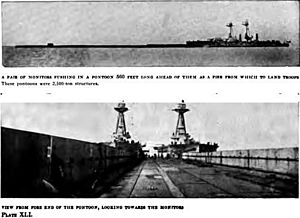

To land soldiers quickly and keep the element of surprise, Admiral Bacon designed special flat-bottomed boats. These boats were called pontoons. They were 550 feet long and 32 feet wide. They were built to be tied between pairs of monitors, which were warships.

Soldiers, guns, wagons, ambulances, and even two male and one female tanks were to be loaded onto each monitor. The monitors would push the pontoons onto the beach. The tanks would then drive off, pulling sledges full of equipment. They would climb the sea-walls, which were about 30 degrees steep. They also had to get over a large stone at the top.

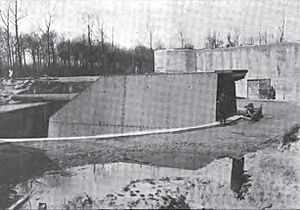

The architect who designed the sea-wall was a refugee in France. He provided his drawings. A copy of the wall was built at Merlimont. A group of tanks practiced climbing it. They used special "shoes" on their tracks and steel ramps. They practiced until they could climb the wall easily.

Experiments on the Thames River showed the pontoons worked very well. They handled bad weather and were easier to move than expected. This made everyone hope they could be used again to bring more soldiers after the first landing. Night landings were also practiced. Wires were stretched between buoys to guide the pontoons close to their landing spot.

Air Support and Artillery

After the German "Operation Beach Party" attack, British air units improved how they worked with artillery. Balloon observers would direct the first shots to get close to a target. Then, airplane observers would take over for the final aiming corrections. Once the airplane observer had aimed the guns, the balloon observer would take over again. This new method saved aircrew. It also allowed telephone talks between the ground and the balloon, as aircraft radios could only send messages.

Airplanes also worked with sound-ranging teams. These teams used microphones to find the position of German guns. If German shelling cut off ground observers, the sound-ranging station could use radio messages from airplanes to find the enemy guns. Balloon observers also helped by reporting gun flashes.

Getting Ready for Battle

British Preparations

In June, the British XV Corps took over the coastal area from French forces. The British artillery was held back at first. The French only allowed their own guns to cover their soldiers. The French positions had three main areas: St Georges, Lombartzyde, and Nieuwpoort Bains. These areas were linked by single bridges across flooded lands. They were also cut off from the rear by the Yser and Dunkirk canals.

The British 1st Division and 32nd Division took over these positions. They had limited artillery support for several days. This was until British guns could arrive. The British commander ordered that these positions must be held. However, the main French defenses were on the other side of the river. The area the British held was more like an outpost. It had only low walls for protection, and no underground shelters for reserve troops.

Tunnelers began digging shelters in the sand dunes. But in early July, few were finished. A defense plan was made on June 28. It relied mainly on artillery. But out of 583 guns, only 176 had arrived by July 8. The rest were supporting other battles and were due by July 15. On the night of July 6-7, German planes bombed the main British airfield near Dunkirk. This caused injuries and damaged planes. Bad weather also made British reconnaissance flights difficult from July 7-9. There were vague reports of more German activity, but flights found nothing unusual. On July 9, all planes were grounded by bad weather.

The British Plan

The landing operation would start at dawn. It would be led by Rear-Admiral Bacon. An army division, about 4,500 men in three groups, would land on the beaches near Middelkirke. Naval ships would bombard the area, and 80 small vessels would create a smoke screen. Fishing boats would carry telephone cables ashore. Tanks would drive off the landing pontoons and climb the sea-wall to protect the landing soldiers.

Each landing group would have four 13-pounder guns and two light howitzers. They would also have a motor machine-gun battery. For quick movement, each group had over 200 bicycles and three motorbikes. Three landing spots were chosen. These were at Westende Bains and Middelkirke Bains. The goal was to cut off German artillery and attack their defenses from behind.

The northern landing group would send a special team to Raversyde. Their job was to destroy a German artillery battery. Then they would move east or south-east to threaten German retreat routes and isolate Ostend. All landing forces were to rush inland towards Leffinghe and Slype. They would capture bridges over the Plasschendaele canal and nearby road junctions.

The XV Corps would break out of the Nieuwpoort area. They would use a barrage from 300 land guns and naval guns. A 1,000-yard advance would be followed by a one-hour pause. Four similar advances over six hours would take the land attack to Middelkirke. There, they would meet the landing force. Three divisions would be kept in reserve. Haig approved this plan on June 18. The 1st Division was chosen for the coastal landing.

German Preparations

On June 19, a German patrol captured eleven British soldiers. This, along with more artillery and air activity, made German Admiral von Schröder believe the British were planning a coastal attack. The Germans planned Unternehmen Strandfest (Operation Beach Party) as a spoiling attack. This meant they would attack first to disrupt the British plans.

The reinforced 3rd Marine Division would lead this attack. Their goal was to capture land east of the Yser river, from Lombartzijde creek to the sea. Parts of the 3rd Marine Division practiced a frontal assault in June. They would have covering fire from eleven torpedo boats. German artillery was also reinforced with 300,000 rounds of ammunition.

The "Langer Max" Gun

In June 1917, the German company Krupp finished building Batterie Pommern at Koekelare. This battery had the Langer Max gun. It was the biggest gun in the world at the time. This gun was very important for the German defense in Flanders. It was used to shell Dunkirk, which was 50 km away. This was to stop supplies from being unloaded. It was also used for distraction attacks. The gun fired its first shot at Dunkirk on June 27. During the Third Battle of Ypres, it also shelled Ypres.

The German Surprise Attack

Operation Beach Party

Unternehmen Strandfest (Operation Beach Party), also known as the Battle of the Dunes, began with German artillery fire on July 6. But it was not heavy enough to suggest a big attack. The morning of July 9 was wet and stormy. Strandfest was delayed for 24 hours.

The next day was cloudy and windy. The German bombardment increased at 5:30 a.m. British floating bridges near the coast were destroyed. Only one bridge and the lock-bridge near Nieuwpoort remained. By 10:15 a.m., telephone and radio contact with the British front was lost. The shelling was heaviest where two British battalions were located. By 11:00 a.m., these battalions were cut off.

Before noon, all German artillery and mortars began firing. The British defensive walls were only 7 feet high and 3 feet thick. They collapsed immediately. Sand jammed the defenders' rifles and machine-guns. The Germans used mustard gas and Blue Cross gas shells for the first time. They mainly used them to attack British artillery. This made the British artillery's response "feeble."

German planes flew low and attacked with machine guns. By late afternoon, British troops on the west bank of the Yser were trapped. The British artillery tried to defend. They fired for one hour at 9:30 a.m., 11:25 a.m., and 2:10 p.m. But these attacks were not effective against German concrete shelters. The German artillery had a 3-to-1 advantage in numbers. Many British guns had not been registered to hide their presence. Only 153 guns fired back.

At 8:00 p.m., German Marine regiments attacked on a 2,000-yard front. They attacked between Lombartzyde and the sea. The main attack moved in five waves, close behind a creeping barrage. Special German assault teams made up the first wave. They reached the third defensive wall, defeated the defenders, and moved to the Yser bank. The second wave overran British troops at the second wall. The third wave advanced to the Yser bank to support the first wave and set up machine-gun nests. The fourth wave carried supplies for building defenses. They also cleared out any remaining British soldiers in the first wall. The fifth wave took over the second wall.

In just twenty minutes, German troops reached the river bank. They cut off any British groups still fighting. About 70-80 percent of the British soldiers had already been killed or wounded by the artillery.

The German attack was very successful. All of the British soldiers in the bridgehead were lost. More than 1,284 prisoners were taken. About forty British soldiers managed to swim the Yser river. But they were caught in the German bombardment. German casualties were about 700 men. Overnight, 64 men from the two British battalions and four tunnelers swam the river. They had hidden in tunnels until dark.

Further inland, the German advance stopped at the second defensive wall. This was because the ground behind it could be easily flooded. A British counter-attack overnight regained the position, except for 500 yards near Geleide Brook. On July 10, German smoke screens, low clouds, and fighter attacks made air observation very difficult. The new front line was mapped from the air late on July 10 and early on July 11.

What Happened Next

After the German Attack

On July 11, the British commander Rawlinson ordered that the lost land be taken back. He wanted to outflank the new German line along the canal in the Dunes area. The XV Corps commander, Du Cane, noted that quick counter-attacks often worked. But those ordered later by higher command were too late. He felt that careful preparation and a planned attack were needed.

The remaining British area was small. The German artillery was still strong. After a successful counter-attack, British troops would be open to another German attack. Du Cane wanted to wait until the rest of the British artillery arrived. He also wanted to wait until the main attack at Ypres had begun. Rawlinson agreed with Du Cane. Counter-attacks planned for July 12 were cancelled.

The 33rd Division moved to the coast in August. They took over the area from Nieuwpoort to Lombartsyde. They spent three weeks there, facing night bombings and gas attacks. Two of the 33rd Division's Scottish battalions, who wore kilts, suffered badly from mustard gas burns. This was until they were given special undergarments.

To keep British preparations secret, crews from 52 Squadron RFC and the 1st Division were kept separate on July 16. They were at a camp called Le Clipon, surrounded by barbed wire. A story was spread that the camp was in quarantine. The 1st Division's artillery was reduced to three 18-pounder batteries and nine tanks. It also had two bicycle battalions, a motor machine-gun battery, and a machine-gun company.

Special fighter patrols were set up to keep German reconnaissance planes away from training areas. Plans were also made for early warnings of German planes approaching Dunkirk. Fighters were ready to intercept them.

Operation Hush Postponed and Cancelled

Operation Hush was changed to include the cancelled counter-attack plan. The attack on Lombartzyde would start from the ground still held by the British. A flank attack would follow shortly after. The attack up the coast and the landings remained unchanged. Haig approved the plan on July 18. It was set to go ahead on August 8. However, the operation was postponed several times before it was cancelled.

On August 24, the 33rd Division raided German outposts. They killed many Germans and took nine prisoners. They lost one killed and sixteen wounded. The next day, the Germans fought back. They recaptured the easternmost post. On August 26, they fired fifteen super-heavy shells into Nieuwpoort. This destroyed the 19th Brigade headquarters. The division was pulled out of the coastal area in early September.

The presence of two British divisions in the coastal area convinced German commanders that a British coastal attack was still possible. The best tidal conditions for a landing would happen again on August 18. The Fifth Army made its second main attack at Ypres on August 16. This was partly to meet the delayed landing date. But it failed to advance far in the most important area. This led to another delay until September 6.

At a meeting on August 22, Haig, Rawlinson, and Bacon discussed three choices. They could delay the coastal operation again. They could do the operation on its own. Or they could move the divisions from XV Corps to the Fifth Army.

Rawlinson favored doing the operation on its own. He thought it would reach Middelkirke. This would bring Ostend within artillery range. It would also make the Germans counter-attack, despite the pressure at Ypres. Bacon wanted the area between Westende and Middelkirke to be taken. This would put 15-inch naval guns within range of Bruges and Zeebrugge. The Zeebrugge–Bruges canal would also be in range, and its locks could be destroyed. Haig rejected this idea. The September operation was postponed again. This time, it was for a night landing under a full moon in the first week of October.

In September, Rawlinson and Bacon became less hopeful. Haig postponed the operation again. But he told them to be ready for the second week of October. The 42nd Division moved from Ypres and took over from another division in late September. They found that the area was often under German artillery fire, bombing, and gas attacks. The coastal area was also under the flight path of German Gotha bombers attacking Dunkirk. Dunkirk was bombed on twenty-three nights in September.

Hopes for Operation Hush rose after the Battle of Broodseinde (October 4) and again after the Battle of Poelcappelle (October 9). But the coastal operation still could not start before the end of the month. After the First Battle of Passchendaele (October 12), Operation Hush was cancelled. On October 14, Rawlinson wrote, "...things have not been running at all smoothly – it is now clear that we shall do nothing on the coast here." The 1st Division left the camp on October 21. The rest of the Fourth Army followed on November 3.

On April 23, 1918, the Dover Patrol carried out the Zeebrugge Raid. They sank ships in the canal entrance to stop U-boats from leaving port. The Belgian Army and the British Second Army began the Fifth Battle of Ypres on September 28, 1918. On October 17, Ostend was captured.

See also

- Dover Patrol

- Zeebrugge Raid

- First Ostend Raid

- Second Ostend Raid

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |