Operations Wallace and Hardy facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Operations Hardy I–Wallace |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Western Front | |||||||

SAS Jeeps in France during Operation Wallace–Hardy I August 1944 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 115 men 2nd Special Air Service | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 7 Killed 8 Wounded 2 captured (later escaped) 16 Jeeps destroyed |

500 killed or wounded 59 vehicles destroyed 1 train derailed |

||||||

Operations Wallace and Hardy I were two important British Special Air Service (SAS) missions during World War II. They took place from July 27 to September 19, 1944. These missions, initially separate, later joined together. Their main goal was to stop German supplies and soldiers from reaching the battlefields in Normandy. They also worked to organize the French Resistance fighters.

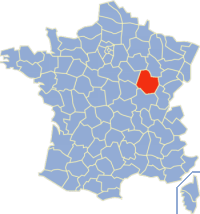

The operations started in the Loire valleys. They then moved through the Forêt de Châtillon area in Burgundy. Finally, they went through the forests of Darney to Belfort. The missions lasted six weeks. They ended when the SAS teams met up with the US Seventh Army. These operations became some of the most successful SAS missions after D-Day.

Contents

The Special Air Service (SAS)

The Special Air Service (SAS) was a special unit of the British Army. It was created in July 1941 by David Stirling. In 1944, the SAS Brigade was formed. It included British, French, and Belgian SAS units.

The SAS used specially changed American Jeeps. These Jeeps were armed with Vickers K machine guns. They were very effective, so the SAS kept using them.

In May 1944, the Allied High Command (SHAEF) ordered the SAS to operate in France. Their job was to parachute behind German lines. They would then support the Allied advance through Belgium, the Netherlands, and into Germany. A key focus was to stop German reinforcements from southern France from reaching the Normandy beachheads. The SAS also hoped for help from the French Resistance. Supplies and more Jeeps would be dropped to them by air.

After the Allied breakout in Normandy in August, many new operations began. The Burgundy region was a key area for SAS activity. This was because German armies would often pass through it to leave France and go to Germany.

Starting the Mission: Operation Hardy I

Operation Hardy I began on July 27. Fifty-five men and seven Jeeps from the 2nd Special Air Service parachuted near Châtillon-sur-Seine. Captain Grant Hibbert led this group. They set up their base in the nearby forest and met local French Resistance fighters.

A month before, 2,000 German soldiers had swept through the area. They killed 37 French Resistance fighters, many after torture. Captain Hibbert knew this situation was dangerous. He carefully checked the German strength and positions in the area.

The SAS men were ordered not to directly fight the Germans. However, many of them still carried out aggressive patrols. They attacked German rail and road communications. These routes were used to move reinforcements. They blew up a railway line between Dijon and Langres. They also destroyed a German convoy heading towards the Normandy front.

Joining Forces: Operation Wallace Begins

As the Allies broke out in Normandy, it became clear that more Germans would retreat through the SAS operation areas. Also, German reinforcements for another big operation in Southern France would pass through this region. Because of this, more SAS soldiers and members of SOE were sent to reinforce the area. More supplies and troops were dropped on August 8, 17, 20, and 23. Later in August, the Hardy I group was joined by a bigger mission, called Wallace.

Operation Wallace started on August 19. Major Roy Farran led sixty men with 20 Jeeps. They landed at Rennes airfield near the Breton capital, which was already under Allied control. Two days later, Farran split his group into three. He told them to keep a thirty-minute distance between groups. This would make it harder for Germans to find them. They also had to avoid all German resistance.

The journey to Hibbert's position took Farran and his men four days. They traveled about 200 miles behind German lines. They headed to the northern bank of the Loire river. The first fifty miles were calm. Local French Resistance fighters helped the SAS avoid German positions. Soon after, some groups met Germans in villages and towns. Most had to fight their way out. Several Jeeps were lost, and eight men were separated. Some escaped and even made their way back to Paris. They later rejoined Farran by parachute.

Farran was left with only seven of his original Jeeps. He kept going. As they neared the forest, the group stopped near a railway line. A train carrying German soldiers appeared. Farran ordered his men to target the engine. It was ripped apart by intense fire from the Jeeps' Vickers K guns. The damaged engine stopped. The SAS men then attacked the German troops at the back of the train. French civilians, including the train crew, jumped out. As they reached their final destination, they attacked a German radar station. They forced the German soldiers there to run away. Prisoners told the SAS that they thought the Jeeps were the advance guard of General George S. Patton's United States Third Army.

Eventually, Farran's group met Hibbert's men at the Hardy I base. Farran took command of the combined group. It had 60 soldiers, 10 Jeeps, and one civilian truck. He ordered them to move to a new base deeper in the forest. This was to avoid more German attention.

The Battle of Châtillon

With their combined force, the SAS decided to attack the German headquarters in Châtillon-sur-Seine. This town was strongly held by the Germans. Farran had met with the local resistance commander earlier. They had agreed that the resistance would help the SAS.

On September 2, in the early morning, just before the attack, there was no sign of resistance support. Farran decided to go ahead with the attack anyway. He worried about a possible betrayal by the French. He also wanted to keep the element of surprise. Under the cover of darkness, Farran placed his squadron in position. They covered all entry and exit points of the town with Jeeps, machine guns, or mortar positions.

At 6:30 AM, the attack began. They fired 3-inch mortars at the châteaux, which was the German headquarters. Forty-eight mortar bombs hit the targets. The SAS faced strong resistance from German troops in the town. A huge firefight broke out. German vehicles caught fire, and many soldiers were killed. Outside the town, a column of 30 vehicles full of German troops was stopped. This prevented them from helping the garrison inside the town.

After seven and a half hours of hard fighting, Farran ordered his men to withdraw to their base. The ambush was a big success for the SAS. About 100 Germans were killed, and many were wounded. Also, nine trucks, four cars, and one motorcycle were destroyed. The SAS had very few casualties: one killed and two wounded. After the battle, the Germans took fifty hostages. They thought the attack came from the Resistance. However, the SAS deliberately left the body of a killed SAS soldier, William Holland. When the Germans found his body, they realized it was not the Resistance, and this prevented the hostages from being executed.

Farran quickly became popular with the French locals. They offered his men wine, flowers, eggs, and butter.

The Final Push

The night after the battle, the SAS received a large drop from the RAF. They got needed supplies, ammunition, and, importantly, several Jeeps by parachute. This brought their total to 18 vehicles. Farran then split his force into two columns of nine vehicles. Hibbert led one column, and Farran led the other. They headed for the Belfort Gap. This area is between the Vosges mountains and the Swiss border. German forces were retreating to this area to try to stop the Allies from reaching the Rhine river. The two columns set off on September 2. They aimed for the gap between Patton's US Third Army in the north and Patch's US Seventh Army in the south. German numbers increased as more and more retreated. But the SAS columns ambushed more German units over the next two weeks.

On September 8, twenty men led by Lieutenant Bob Walker-Brown acted on a tip from the French Resistance. They ambushed five German petrol tanker trucks going from Langres to Dijon. In an ambush style, a motorcycle with a sidecar and a lorry were allowed to pass. Then, the first and last vehicles were hit. The tanker trucks were systematically destroyed and burst into flames. With all the tankers destroyed and huge clouds of smoke created, the SAS successfully pulled back.

In the final week, the SAS set up a base in the forest around Darney. In the coming days, there were fewer Germans, and hardly any resistance. Wallace ended on September 17. The groups met up with the first parts of the US Seventh Army not far from Belfort.

What Happened After?

During the month they were active, the SAS men caused more than 500 German casualties. They also destroyed 23 staff cars, 6 motorcycles, and 36 other vehicles. These included trucks, half-tracks, and troop carriers. In addition, 100,000 tons of petrol were destroyed, and a goods train was burned out.

Seventeen SAS soldiers were lost. One was in a parachuting accident. Two were captured but both escaped. Jeep losses were the highest, with 16 destroyed. Some were lost due to mechanical problems or damage from parachute drops. The Royal Air Force supplied them throughout their time behind German lines. They flew 36 missions, bringing the SAS twelve new Jeeps and 36 supply containers.

The Germans mistakenly thought Farran's squadron was the advance guard of the 3rd U.S. Army. Because of this, they left Châtillon sooner than they needed to. Farran's small force played a big part in confusing the German forces in front of that army. In a December report, the Allied High Command (SHAEF) noted that the raid was very successful. A small force behind German lines caused huge damage, much more than expected for their size, with very few losses. Farran himself said the raid proved David Stirling's original ideas for the SAS. He believed that small units behind enemy lines could bother the Germans and create a big advantage.

After meeting with American forces, Farran sent the squadron back to Paris. He gave them a week of leave in the capital. Farran received an important medal, the Distinguished Service Order, for Operation Wallace.

Farran and his men later retrained. They then went to join the Italian Campaign. There, they prepared for Operation Tombola the following year in March, which was also a great success.

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |