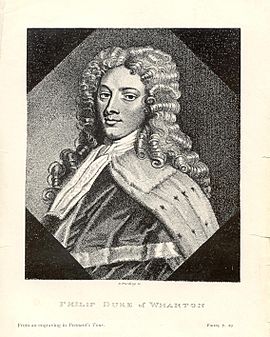

Philip Wharton, 1st Duke of Wharton facts for kids

Philip Wharton, 1st Duke of Wharton (born December 21, 1698 – died May 31, 1731) was an English nobleman and politician. He was known for being one of the few people in English history to become a duke while still a teenager. He was also not closely related to the king. Philip Wharton was involved in Jacobitism, a movement that supported the return of the old royal family to the throne.

Contents

Early Life

Family and Education

Philip Wharton was the son of Thomas Wharton, 1st Marquess of Wharton, a well-known politician. His mother was Lucy Loftus. Philip received a good education, which prepared him for public speaking. He was known for being very eloquent and witty, meaning he could speak well and make clever jokes.

In 1715, when Philip was just sixteen, his father passed away. Philip then inherited his father's titles, becoming the 2nd Marquess of Wharton and the 2nd Marquess of Malmesbury in Great Britain. He also became the 2nd Marquess of Catherlough in Ireland. His father's large estates were managed by his mother and his father's friends.

First Travels and Titles

After his father's death, young Philip began to travel. He visited France and Switzerland with a strict tutor. Philip did not like his tutor's authority. During his travels, he met James Francis Edward Stuart, also known as the "Old Pretender." James was the son of King James II. In 1716, James gave Philip the title of Duke of Northumberland in the Jacobite peerage.

Philip then went to Ireland. At just 18 years old, he became a member of the Irish House of Lords as Marquess of Catherlough. A year later, in 1718, King George I made him the Duke of Wharton. This was done to try and gain Philip's support for the King. In 1719, Philip and his wife, Martha Holmes, had a son named Thomas. Sadly, the child died the next year during a smallpox outbreak.

Political Journey

Shifting Loyalties

While traveling in 1716, Philip Wharton became involved with the Jacobite cause. He even started signing his name "Philip James Wharton" to show his support. Because he was a powerful speaker and a nobleman with a seat in the House of Lords, both the new King's supporters and the Jacobites wanted him on their side.

Financial Challenges

Philip Wharton faced serious financial problems. Even before the South Sea Bubble stock market crash in 1720, he had many debts. He sold his estates in Ireland and used the money to invest in the South Sea Company. When the stock market crashed, he lost a huge amount of money. To show his feelings about this loss, he even held a public "funeral" for the South Sea Company.

Wharton continued to borrow money, often from Jacobite supporters. In 1719, he is believed to have started the original Hellfire Club. This club mainly performed playful imitations of religious ceremonies. In 1723, he became the Grand Master of the Premier Grand Lodge of England, a large group of Freemasons.

Public Speaking and Writing

Philip Wharton was very active in the House of Lords, often speaking against Robert Walpole, a powerful politician. In 1723, he spoke and wrote to support Francis Atterbury, a bishop accused of Jacobite sympathies. Wharton also published a newspaper called The True Briton. In this paper, he wrote against Walpole's growing power. He explained that he supported the "Pretender" not for religious reasons, but because he believed Walpole had betrayed the true principles of his father's political party.

His support for the Jacobite cause became stronger in 1725. He joined other noblemen in criticizing the King's court. He also made friends with politicians in the City of London. This was important for the Jacobites, as their support had mostly come from other parts of the country.

Later Years and Legacy

Life Abroad

Philip Wharton's debts became too large to manage. In 1725, he took a position as a Jacobite ambassador to the Holy Roman Empire in Vienna. However, the Austrians did not think he was a good diplomat. He then traveled to Rome, where James, the "Pretender," gave him the Order of the Garter, a special honor. Wharton wore this publicly.

In 1726, Wharton's first wife passed away. Just three months later, he married Maria Theresa O'Neill O'Beirne. She was a Maid of Honour to the Queen of Spain. Philip's actions were watched by spies, and some other Jacobites found his behavior difficult.

In 1728, Wharton helped write for Mist's Weekly Journal. He wrote a famous letter that caused the government to react strongly, leading to arrests and the destruction of printing presses. Walpole offered Wharton a pardon and to clear his debts if he stopped writing against the government. That same year, Wharton wrote a powerful piece explaining his reasons for leaving England.

Final Years

Wharton soon struggled to find money and even had to take food from people he knew. He sold his title back to King George I. He then joined the Jacobite forces in the Spanish army, fighting against England. This meant he was fighting against his home country. In 1727, during the siege at Gibraltar, Wharton bravely led his men and was wounded in the foot.

Before being charged for acting against his country, Wharton tried to make peace with King George. He even offered to share information with Walpole's spies, but they did not think he was useful. He returned to Madrid and lived on his army pay. After an argument with a servant, he was briefly imprisoned and then sent away.

In 1730, Philip Wharton gave up his support for James and the Jacobite cause. He passed away on May 31, 1731. His titles, except for Baron Wharton, ended with his death. The title of Baron Wharton was inherited by his sister, Jane Wharton, 7th Baroness Wharton. His widow returned to London and lived comfortably.

See also

- Gormogons