Photios I of Constantinople facts for kids

Quick facts for kids SaintPhotios the Great |

|

|---|---|

Photios baptising the Bulgarians

|

|

| The Great, Confessor of the Faith, Equal to the Apostles, Pillar of Orthodoxy | |

| Born | c. 810 Constantinople, Byzantine Empire (modern-day Istanbul, Turkey) |

| Died | c. 893 Bordi, Armenia |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Canonized | 1847, Constantinople, Ottoman Empire, by Anthimus VI of Constantinople |

| Feast | February 6 |

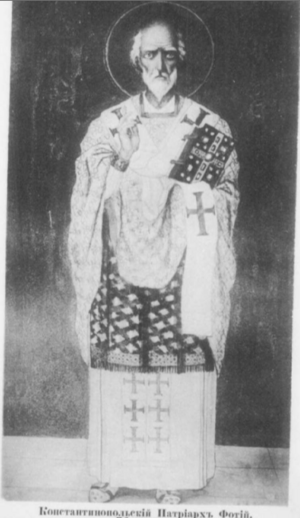

Saint Photios the Great (born around 810/820, died February 6, 893) was a very important leader in the Eastern Orthodox Church. He served as the top church leader, called the Ecumenical Patriarch, in Constantinople twice: from 858 to 867, and again from 877 to 886.

Many people consider Photios to be one of the most powerful and influential church leaders in Constantinople's history. He was also seen as the smartest person of his time, a "leading light" during a period of great learning. Photios played a key role in helping the Slavs become Christians. He was also central to a major disagreement between the Eastern and Western Churches, known as the Photian schism.

Photios was a very educated man from a noble family in Constantinople. His great-uncle, Saint Tarasius, was also a Patriarch of Constantinople. Photios first wanted to be a monk, but he chose to become a scholar and a statesman instead.

In 858, the Byzantine Emperor Michael III decided to remove Patriarch Ignatius from his position. Photios, who was not even a priest yet, was chosen to replace him. This caused a lot of arguments between the Pope in Rome and the Byzantine Emperor. Later, Ignatius was put back in charge. When Ignatius died in 877, Photios became Patriarch again, with the approval of the new Pope, John VIII.

The Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church have different views on some church councils from this time. These disagreements show the end of the early unity of the Christian Church. The Eastern Orthodox Church officially recognized Photios as a saint in 1847.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Most of what we know about Photios comes from people who did not like him. For example, his rival Ignatius's biographer, Nicetas the Paphlagonian, was very critical of him. Because of this, modern historians are careful when reading these old stories.

We do not know much about Photios's early life. We know he came from an important family. His uncle, Saint Tarasius, was the Patriarch of Constantinople from 784 to 806. During a time when religious images (icons) were being destroyed, Photios's family suffered because his father, Sergios, strongly supported icons. His family only regained favor after icons were restored in 842.

Some scholars believe Photios might have been partly of Armenian descent. Others simply call him a "Greek Byzantine". Emperor Michael III once called Photios "Khazar-faced," but it is unclear if this was an insult or a hint about his background.

Photios received an excellent education, but we do not know where he studied. He owned a huge library, which shows how much he knew about many subjects. These included theology, history, philosophy, law, and science. Most experts believe he did not teach at the Magnaura or any other university. However, he may have taught young students at his home, which was a center for learning. He was also friends with the famous scholar Leo the Mathematician.

Photios once said that he wanted to become a monk when he was young. But he chose a career in public service instead. He likely got his start because his brother, Sergios, married Irene, the sister of Empress Theodora. Theodora became the ruler of the Byzantine Empire after her husband, Emperor Theophilos, died in 842. Photios became a high-ranking official, serving as a captain of the guard and later as chief imperial secretary. At some point, he also went on an important trip to Baghdad to meet the Abbasids.

Photios became famous as a scholar. He was known for his cleverness. Once, during an argument with Patriarch Ignatius, Photios made up a silly idea that people have two souls. He did this just to trick Ignatius into taking it seriously and looking foolish. Then Photios admitted he was joking. A historian called this "perhaps the only really satisfactory practical joke in the whole history of theology."

Becoming Patriarch

Photios's church career took off quickly after Bardas, a powerful relative of the young Emperor Michael III, took control of the government in 856. In 858, Bardas had a disagreement with Patriarch Ignatius. Ignatius refused to let Bardas into the main church, Hagia Sophia. Because of this, Bardas and Michael arranged for Ignatius to be removed and confined, saying he was a traitor. This left the Patriarch's position empty.

The position was soon filled by Photios, who was related to Bardas. On December 20, 858, Photios became a monk. Over the next four days, he quickly became a lector, sub-deacon, deacon, and priest. Then, on Christmas Day, Photios was made a bishop and became the Patriarch.

The quick removal of Ignatius and Photios's fast rise caused a lot of debate. Supporters of Ignatius asked the Church of Rome for help. Since Photios's election was unusual, Pope Nicholas I got involved to decide if it was proper. In 863, the Pope held a meeting in Rome and removed Photios from his position, saying Ignatius was the true Patriarch. This started a major split, known as the Photian schism.

Four years later, Photios responded by holding his own church meeting. He removed the Pope from the church, saying the Pope was teaching wrong ideas. This was about the idea of the Holy Spirit coming from both the Father and the Son. The situation was also complicated by who had authority over the whole Church and who controlled the newly Christianized land of Bulgaria.

Return to Power and Later Years

Things changed when Photios's supporters, Bardas and Emperor Michael III, were killed in 866 and 867. Basil the Macedonian took over as emperor. Photios was removed as Patriarch, not just because he was connected to Bardas and Michael, but because Basil wanted to make an alliance with the Pope. Photios was sent away around September 867, and Ignatius was put back in charge on November 23. A church council in 869–870 officially condemned Photios, ending the split for a time. However, during his second time as Patriarch, Ignatius followed policies very similar to Photios's.

Not long after being condemned, Photios became friends with Basil again. He even became a teacher to the emperor's children. Letters from Photios during his time away show that he tried to convince the emperor to bring him back. Some stories say that Photios even made up a fake family history for Basil, claiming he was from a royal family. This story shows how much Basil relied on Photios for his knowledge and ideas.

After Photios was called back, he and Ignatius met and publicly made up. When Ignatius died on October 23, 877, Photios naturally took his place as Patriarch three days later. Some historians believe that from this point on, Basil was greatly influenced by Photios.

Photios then received official recognition from the Christian world at a church council in Constantinople in November 879. Representatives from Pope John VIII attended and agreed to accept Photios as the rightful Patriarch. The Pope was criticized by some in the West for this. Photios stood firm on the main points of disagreement between the Eastern and Western Churches. These included the Pope's demand for an apology, who had church control over Bulgaria, and the Western Church's addition of the filioque to the Nicene creed.

In the end, Photios refused to apologize or accept the filioque. The Pope's representatives accepted his agreement to return Bulgaria to Rome's control. However, this was mostly a symbolic move. Bulgaria had already returned to the Byzantine rite in 870 and had its own independent church. Without the agreement of Boris I of Bulgaria, the Pope could not force his claims. Photios also worked to improve relations with the Armenian kingdom to the east. He tried twice to bridge the differences between the Greek Orthodox and Armenian churches, but his efforts were not successful.

During arguments between Emperor Basil I and his son, Leo VI, Photios supported the emperor. In 883, Basil accused Leo of planning against him and kept him confined in the palace. Basil even thought about blinding Leo, but Photios and another official convinced him not to. In 886, Basil found out about another plot against him, but Leo was not involved. Photios, however, might have been part of this plot.

Basil died in 886 after a hunting accident. Some historians believe Leo VI might have been involved in his death, as Leo became emperor right after. Leo removed Photios from his position, even though Photios had been his teacher. Photios was replaced by Leo's brother, Stephen, and sent away to a monastery in Armenia. Letters confirm that Leo made Photios resign.

In 887, Photios and his friend, Theodore Santabarenos, were put on trial for treason. While some sources say the trial ended without a conviction, others state that Photios was banished to a monastery where he later died. Latin sources confirm that while he was not completely removed from the church, his church career was seen as a disgrace by Catholic leaders. Many of his theological ideas were also condemned after his death.

However, it seems Photios was not disliked for the rest of his life. He continued to write during his exile. Emperor Leo probably restored his good name within a few years. In a text about his brothers, written around 888, Leo spoke highly of Photios, calling him a rightful archbishop who brought unity. This is different from how Leo treated him earlier. The fact that Photios's body was allowed to be buried in Constantinople also suggests he was rehabilitated. After his death, his supporters tried to have him recognized as a saint. A leading member of Leo's court, Leo Choirosphaktes, even wrote a poem honoring Photios. However, some historians note that Photios's death seemed quite quiet for such an important figure. Leo did not allow him back into politics, which might explain why his passing was not widely celebrated.

The Eastern Orthodox Church honors Photios as a saint, with his feast day on February 6. Ignatius is also honored as a saint in both the Eastern Orthodox and Catholic Churches.

His Importance

Photios is one of the most famous people from the 9th century in the Byzantine Empire and throughout its history. He was one of the most educated men of his time. Even some of his opponents respected him as the most productive theologian. He became famous for his role in church conflicts, but also for his intelligence and his many writings.

Historian Vasileios N. Tatakes saw Photios as someone who focused more on practical matters than on deep theories. He believed that Photios helped bring humanism into Orthodoxy, making it a key part of the Byzantine people's identity. Tatakes also argued that Photios understood this national identity and became a defender of the Greek nation and its spiritual freedom in his debates with the Western Church.

Adrian Fortescue called him "one of the most wonderful men of all the middle ages." He stressed that if Photios had not been part of the great church split, he would always be remembered as the greatest scholar of his time. However, Fortescue also strongly criticized Photios's involvement in the split. He believed Photios's ambition led him to be dishonest in trying to keep his position as Patriarch.

Writings and Works

Photios was a very active writer. His works cover many topics, showing his wide knowledge.

The Bibliotheca

Photios's most important work is his Bibliotheca, also known as Myriobiblon. This is a collection of summaries and shorter versions of 280 books by classical authors. Many of the original books are now lost, so Photios's work is very valuable. It is especially rich in summaries from historical writers.

Thanks to Photios, we have almost all we know about writers like Ctesias and Memnon of Heraclea. We also have parts of lost books by Diodorus Siculus and lost writings by Arrian. The Bibliotheca also includes many works on theology and church history. However, it almost completely ignores poetry and ancient philosophy. It seems Photios did not think it was necessary to write about authors that every educated person would already know. His literary criticisms are often very insightful, and the summaries vary in length. The many notes about authors' lives probably came from a work by Hesychius of Miletus.

Some older scholars thought the Bibliotheca was put together in Baghdad when Photios was on his trip there. This was because many of the books mentioned were rarely cited during the "Byzantine Dark Ages" (around 630-800 AD). Also, the Abbasids were interested in Greek science and philosophy. However, experts on this period, like Paul Lemerle, have shown that Photios could not have written his Bibliotheca in Baghdad. Photios himself said that he sent his brother summaries of books he had read before his trip, from his youth. Also, the Abbasids were only interested in Greek science, philosophy, and medicine. They did not translate Greek history, rhetoric, or other literary works. They also did not translate Christian writers. Most of the works in Bibliotheca are by Christian authors, and most of the non-religious texts are histories, grammars, or literary works. This further shows that most of the books could not have been read while Photios was in the Abbasid Empire.

Other Important Works

The Lexicon (Λέξεων Συναγωγή) was published after the Bibliotheca. It was probably mostly written by his students. It was meant to be a reference book to help people read old classical and religious authors whose language was outdated. For a long time, only incomplete copies of the Lexicon existed. But in 1959, a complete copy was found in a monastery in Greece.

His most important theological work is the Amphilochia. This book contains about 300 questions and answers on difficult parts of the Bible. It was written for Amphilochius, the archbishop of Cyzicus. Other similar works include his four-book treatise against the Manichaeans and Paulicians, and his arguments with the Latins about the Holy Spirit. Photios also wrote a long letter of religious advice to the newly Christianized Boris I of Bulgaria. Many other letters also survive.

Photios also wrote two "mirrors of princes," which are guides for rulers. One was for Boris-Michael of Bulgaria, and the other for Leo VI the Wise.

Photios's summary of Philostorgius' Church History is the main source for that work, which is now lost.

The first English translation of Photios's "Mystagogy of the Holy Spirit" was published in 1983. Another translation came out in 1987.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Focio para niños

In Spanish: Focio para niños

- Byzantine philosophy

- Filioque clause

- University of Magnaura

- Bibliotheca (Photius)

- Bibliotheca (Pseudo-Apollodorus)

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |