Pierre Berton facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Pierre Berton

CC OOnt

|

|

|---|---|

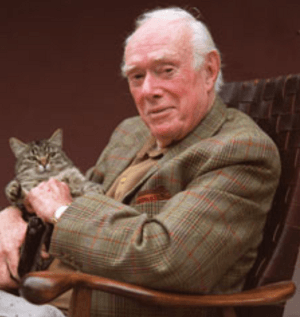

Berton and Ruby in their later years at Kleinburg, Ontario

|

|

| Born | Pierre Francis de Marigny Berton July 12, 1920 Whitehorse, Yukon, Canada |

| Died | November 30, 2004 (aged 84) Toronto, Ontario, Canada |

| Resting place | Kleinburg, Ontario, Canada |

| Occupation | Author, journalist, broadcaster |

| Alma mater | University of British Columbia |

| Genre | Canadiana, Canadian history |

| Notable awards | Companion of the Order of Canada Order of Ontario Governor General's Award for English-language non-fiction (1956, 1958, 1971, 1988) John Drainie Award Stephen Leacock Memorial Medal for Humour Gabrielle Léger Award for Lifetime Achievement in Heritage Conservation National Newspaper Award Governor General’s History Award |

| Spouse |

Janet Berton

(m. 1946) |

| Children | 8 |

Pierre Berton (born July 12, 1920 – died November 30, 2004) was a very famous Canadian writer, journalist, and TV host. He wrote over 50 best-selling books. Many of his books were about Canadian history and popular culture. He also wrote books for children and historical works for young people. Pierre Berton was a reporter, a war correspondent, and an editor for major magazines and newspapers. He was also a regular guest on the popular TV show Front Page Challenge for 39 years. He helped start the Writers' Trust of Canada and won many awards for his work.

Contents

Growing Up in the Yukon

Pierre Berton was born on July 12, 1920, in Whitehorse, Yukon. His father had moved there because of the 1898 Klondike Gold Rush. In 1921, his family moved to Dawson City, Yukon. His mother, Laura Beatrice Berton, was a school teacher. She wrote a book about her life in the Yukon called I Married the Klondike.

Dawson City was a very remote place back then. Pierre grew up meeting many interesting people who had come north for the gold rush and stayed. These experiences gave him a special way of looking at the world.

In 1932, his family moved to Victoria, British Columbia. When he was 12, Pierre joined the Scout Movement. He later said that Scouting really helped him. He even started his journalism career by writing for a small newspaper put out by his Scout troop. He stayed in Scouting for seven years.

Like his father, Pierre Berton worked in Klondike mining camps during his university years. He studied history at the University of British Columbia. He also worked on the student newspaper there, called The Ubyssey.

Starting His Journalism Career

Pierre Berton began his newspaper career in Vancouver. At just 21, he became the youngest city editor on a Canadian daily newspaper. This happened because many older staff members had joined the army for Second World War.

In February 1942, he saw Japanese-Canadians being held in Vancouver before being sent to special camps. Their businesses and homes were taken by the government.

Serving in the Military

Berton was called to join the Canadian Army in 1942. He trained in British Columbia. At first, he was a "Zombie," which was a nickname for soldiers who were conscripted but only served in Canada. However, Berton chose to "go Active," meaning he volunteered to fight overseas. He felt it was important to take a stand in the war.

He became a Lance Corporal and then a Corporal, teaching basic training. He also trained to become an officer. Berton spent several years taking many military courses. He was told many times that he would go overseas, but each time his orders were cancelled.

In March 1945, he finally went overseas to the UK. He trained to be an Intelligence Officer. By the time he finished his training, the war in Europe had ended. He volunteered for the war against Japan, but Japan surrendered before he could see combat.

Becoming a Famous Journalist

In 1947, Pierre Berton went on an adventure to the Nahanni River. His stories about this trip for the Vancouver Sun newspaper were picked up by other news services. This made him a well-known adventure writer.

In 1948, Berton wrote an important article for Maclean's magazine called "They're Only Japs." This was one of the first times a Canadian magazine wrote about the unfair treatment of Japanese-Canadians during the war. Berton interviewed people who had been held in camps. He criticized the government's decision to intern all Japanese-Canadians. He also pointed out that some people wanted to seize their property.

War Correspondent in Korea

In 1951, Berton became a war correspondent for Maclean's magazine in the Korean War. He really wanted to report from the front lines. He arrived in South Korea in March 1951. This was a critical time, as Chinese forces had just taken Seoul.

Berton reported on the "war of the hills," where soldiers fought over small hills that didn't change the overall war much. He wrote that Canadian soldiers were frustrated by this. He also noted that Canadian soldiers respected the fighting skills of their Chinese enemies.

Editor and TV Star in Toronto

Berton moved to Toronto in 1947. At 31, he became the managing editor of Maclean's. In the 1950s, he wrote articles about his travels in Canada's far north. These stories were later published in his 1956 book, The Mysterious North. This book made him known as an expert on the North.

In 1957, he joined the CBC's public affairs show, Close-Up. He also became a regular on the popular TV show Front Page Challenge. That same year, he narrated a documentary called City of Gold, which was about his hometown of Dawson City during the gold rush.

In 1958, he published his best-selling book, Klondike The Last Great Gold Rush. This book told the story of the thousands of people who faced great challenges to find gold in the Klondike. Berton's own experience growing up in the Yukon made the book feel very real.

Berton joined The Toronto Star newspaper in 1958. He wrote columns for the paper. In 1959, he went to Cairo, Egypt, to interview President Gamal Abdel Nasser. While waiting, he made a documentary about life in Egypt, which broadened his views.

In 1960, Berton did an experiment to show that some resorts were refusing to rent rooms to Jewish people. He sent letters from a "Sol Cohen" and a "D.M. Douglas" to many resorts. Most resorts replied to "Douglas" but not to "Cohen," or said they were full. Berton wrote about this in his column, which caused a big discussion and led to demands to end such unfair practices.

He also visited Japan in 1960 and was amazed by how much it had rebuilt after World War Two. He was saddened by how traditional Japanese culture seemed to be fading.

In 1961, Berton wrote a children's book called The Secret World Of Og. He based it on stories he used to tell his daughters. His publisher wasn't sure it would sell well, but it became very popular. Berton always answered fan mail from children who loved the book.

A Public Figure

In 1962, Berton left the Star to start his own TV show, The Pierre Berton Show, which ran until 1973. He became one of Canada's most well-known public thinkers. He could get many famous people to appear on his show.

In 1963, his show featured an interview with Pierre Trudeau, who later became Prime Minister of Canada. Trudeau talked about Quebec's place in Canada and criticized separatism. This interview helped introduce Trudeau to a wider English-Canadian audience.

In 1964, Berton interviewed Mick Jagger and the other members of the newly formed Rolling Stones for his show. He asked Jagger if he felt he was a bad influence on young people. Jagger replied, "I don't feel morally responsible for anyone." This show helped make the Rolling Stones and British youth culture popular in Canada.

In 1965, Berton published The Comfortable Pew, a book that criticized the Anglican Church. It sold 100,000 copies very quickly.

Starting in 1968, Berton decided to focus on writing Canadian history. He wanted to write popular, easy-to-read stories about Canada's past. His first big project was about the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) in the 19th century. He saw the CPR as a huge achievement that helped make Canada a true nation. He wrote two books about it: The National Dream and The Last Spike.

His TV show continued to feature famous guests. In 1971, Berton interviewed Bruce Lee, which was the famous martial artist's only surviving TV interview. Berton also hosted and wrote for other TV shows like My Country and The National Dream. He also had a daily radio show called Dialogue with Charles Templeton.

Becoming a Historian

In 1970, The National Dream was published and became a big success. The second book, The Last Spike, came out in 1971 and was even more popular. These books made Pierre Berton a "national institution" – a very important figure in Canadian history storytelling. People even bought souvenirs related to The Last Spike!

Historians praised Berton's books for being lively and exciting. He described how railroad builders had to blast their way through the Rocky Mountains, which was a very difficult and dangerous job.

In the 1970s, Canada faced tough times. Berton felt the country needed another inspiring story. He chose the War of 1812 as his next topic. He wrote The Invasion of Canada (1980) and Flames Across the Border (1981). Berton believed the War of 1812 helped create a Canadian national identity. His books on this war were very popular with Canadians.

In his 1984 book The Promised Land, he wrote about the settlement of the Prairie provinces. He showed the difficulties and hardships faced by the farmers. In 1986, he published Vimy, about the Battle of Vimy Ridge in 1917, which was also very successful.

Later Years and Retirement

In 1992, Berton published Niagara: A History, about the people connected to Niagara Falls. These books didn't sell as well as his earlier works. This marked a time when his popularity as a public intellectual started to decline.

In 2004, Pierre Berton published his 50th book, Prisoners of the North. After this, he announced that he was retiring from writing. On October 17, 2004, a new library in Vaughan, Ontario, was named the Pierre Berton Resource Library in his honor. He had lived in nearby Kleinburg, Ontario, for about 50 years.

Personal Life

Pierre Berton married Janet Walker in 1946. They had eight children together. Berton was an atheist, meaning he did not believe in God.

Death

Pierre Berton passed away on November 30, 2004, at the age of 84, from heart failure. His ashes were scattered at his home in Kleinburg. He was survived by his wife, eight children, and 14 grandchildren.

Legacy

The Pierre Berton Award was created in 1994 by Canada's National History Society. It is given each year to someone who does an excellent job of sharing Canadian history in an interesting way. Pierre Berton was the first person to receive this award, and he agreed to let it be named after him.

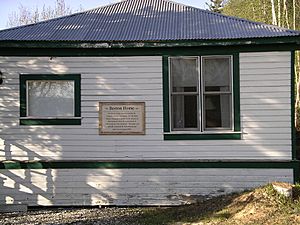

His childhood home in Dawson City, Yukon, is now called Berton House. It is used as a special place where professional Canadian writers can stay and work. This helps support new writers and adds to the literary community in Dawson City.

A school in Vaughan, Ontario, was named Pierre Berton Public School in September 2011. The Berton family visited the school for its official opening.

Awards and Honors

Pierre Berton received many important awards and honors throughout his life:

- Order of Canada, Officer, 1974.

- Order of Canada, Companion, 1986 (Canada's highest honor).

- Canadian Booksellers Award, 1982.

- Canadian Authors Association Literary Award for non-fiction, 1981.

- Queen Elizabeth II Silver Jubilee Medal 1977.

- 125th Anniversary of the Confederation of Canada Medal 1992.

- Queen Elizabeth II Golden Jubilee Medal 2002.

- Nellie Award, best public affairs broadcaster in radio, 1978.

- Governor General's Awards for: The Last Spike, 1972; Klondike, 1958; The Mysterious North, 1956.

- Stephen Leacock Medal for Humour, 1959.

- Responsibility in Journalism presented by the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (CSICOP), 1996.

- Member of Canada's Walk of Fame, inducted in 1998.

- Toronto Humanist of the Year 2003.

- Member of the Order of Ontario, 1992.

Honorary Degrees

Pierre Berton also received many honorary degrees from universities, recognizing his important work:

| Country | Date | School | Degree |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1973 | University of Prince Edward Island | Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) | |

| Spring 1974 | York University | Doctor of Letters (D.Litt.) | |

| 1978 | Dalhousie University | Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) | |

| June 5, 1981 | Brock University | Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) | |

| June 6, 1981 | University of Windsor | Doctor of Letters (D.Litt.) | |

| 1982 | Athabasca University | Doctor of Athabasca University (D.AU) | |

| May 1983 | University of Victoria | Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) | |

| November 1983 | McMaster University | Doctor of Letters (D.Litt.) | |

| May 18, 1984 | Royal Military College of Canada | Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) | |

| 1984 | University of Alaska Fairbanks | Doctor of Fine Arts (DFA) | |

| May 30, 1985 | University of British Columbia | Doctor of Letters (D.Litt.) | |

| 1988 | University of Waterloo | Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) | |

| June 7, 2002 | University of Western Ontario | Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) |

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Pierre Berton para niños

In Spanish: Pierre Berton para niños