Polaris expedition facts for kids

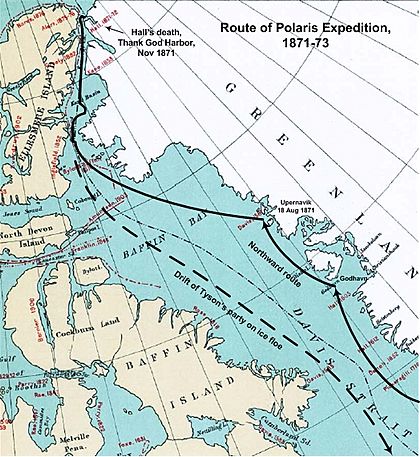

The Polaris expedition was an important journey to the Arctic from 1871 to 1873. It was one of the first big attempts to reach the North Pole. The expedition was paid for by the U.S. government. Its main success was reaching 82° 29′ North by ship, which was a new record at the time.

The expedition was led by Charles Francis Hall. He was an experienced explorer who had lived with the Inuit people in the Arctic. Hall was very good at surviving in the Arctic. However, he had no experience leading a large group of people or commanding a ship. He got the job because he knew so much about the Arctic.

The Polaris left New York City in June 1871. Right from the start, the expedition had problems with leadership. Some crew members, especially chief scientist Emil Bessels and meteorologist Frederick Meyer, did not respect Hall. They thought he was not qualified. Many German crew members supported Bessels and Meyer. This caused a lot of tension and divided the crew.

By October, the crew was spending the winter in Thank God Harbor, Greenland. They were getting ready for the trip to the North Pole. Hall returned to the ship after an exploration trip and suddenly became very sick. Before he died, he accused some crew members, especially Bessels, of poisoning him. Later, 19 members of the expedition got separated from the ship. They drifted on a large piece of ice for six months and 1,800 miles before being rescued. The damaged Polaris was run aground and wrecked in October 1872. The remaining men survived the winter and were rescued the next summer.

A naval investigation looked into Hall's death. No one was charged at the time. However, in 1968, Hall's body was examined. It showed he had swallowed a lot of arsenic in the last two weeks of his life. This made people wonder if Bessels had poisoned him.

Contents

Getting Ready for the Journey

Why the Expedition Started

In 1827, William Edward Parry led a British navy trip to reach the North Pole. For the next 50 years, Americans tried three times to reach the Pole. These trips included Elisha Kent Kane in 1853–1855, Isaac Israel Hayes in 1860–1861, and Charles Francis Hall with the Polaris in 1871–1873.

Charles Francis Hall was a businessman from Cincinnati. He had no special schooling or sailing experience. He had worked as a blacksmith and an engraver. He even ran his own newspaper for a few years. Hall was full of energy and loved new ideas. He was very interested in hot air balloons and the new transatlantic telegraph cable. He also loved reading, especially about the Arctic. Hall became focused on the Arctic around 1857. This was when people realized that John Franklin's Arctic trip from 1845 was likely lost forever.

Hall spent years studying old explorer reports. He also tried to raise money for his own trip. Because of his strong personality, he was able to lead two solo trips. These trips were to search for Franklin and his crew. One trip was in 1860 and another in 1864. These experiences made him a skilled Arctic explorer. He also made important friends among the Inuit people. His fame helped him convince the U.S. government to pay for a third trip. This time, the goal was to reach the North Pole.

Money and Supplies

In 1870, the United States Senate suggested a plan to pay for a North Pole expedition. Hall, with help from Navy Secretary George M. Robeson, worked hard to get the money. He received a $50,000 grant to lead the trip. He started hiring people in late 1870.

Hall got a Navy tugboat called Periwinkle. It was a 387-ton steamship. At the Washington Navy Yard, the ship was changed into a schooner. It was renamed Polaris. To prepare it for the Arctic, thick oak wood was added to its sides. The front of the ship was covered in iron. A new engine was put in. One of the boilers was changed to burn seal or whale oil. The ship also had four whaleboats, each about 20 feet long and 4 feet wide. It also had a flat-bottomed scow.

Hall had seen and admired the Inuit umiak on his earlier trips. This was an open boat made of wood, whalebone, and animal skins. He brought a similar boat that could fold up and hold 20 people. The food on board included canned ham, salted beef, bread, and sailor's biscuits. They planned to eat fresh musk ox, seal, and polar bear meat. This would help them avoid scurvy, a sickness caused by not enough vitamins.

The Crew

In July 1870, Ulysses S. Grant, the President of the United States, named Hall as the leader. He was called captain, but it was an honorary title. Hall had a lot of Arctic experience, but no sailing experience. Hall chose many whalers for his officers and crew. These were men who knew Arctic waters well. This was different from British trips, which usually used navy officers and very strict crews.

For his main sailing officer, Hall first asked Sidney Ozias Budington. Then he asked George Emory Tyson. Both said no at first because they had whaling jobs. But when their jobs fell through, Hall made Budington the sailing master and Tyson his assistant. Budington and Tyson had many years of experience leading whaling ships. So, the Polaris actually had three "captains." This caused many problems for the expedition. To make things worse, Budington and Hall had argued before, in 1863. Budington had not let Hall bring his Inuit guides, Ipirvik and Taqulittuq, north. They were sick and Budington was caring for them.

The rest of the crew included Americans and Germans. There was also a Dane and a Swede who were close with the Germans. The first mate, Hubbard Chester, and the second mate, William Morton, were American. The chief scientist and doctor, Emil Bessels, and the chief engineer, Emil Schumann, were German. Most of the regular sailors were also German.

Besides the 25 officers, crew, and scientists, Hall brought his native companions. These were the people who had helped him on his earlier trips. They included the guide and hunter Ipirvik, and the interpreter and seamstress Taqulittuq, along with their baby son. Later, at Upernavik, Hans Hendrik also joined. He was a respected Greenlandic Inuk hunter. He had helped on earlier expeditions and was key to their survival. Bessels wrote that Hans insisted on bringing his wife and three young children. Hall did not want to add "four useless mouths," but he agreed.

The Journey Begins

Even before the ship left Brooklyn Navy Yard on June 29, 1871, there were crew problems. The cook, a sailor, a fireman, and an assistant engineer all left the ship. The ship stopped in New London to get a new assistant engineer. It left again on July 3. By the time the ship reached St. John's, there was already disagreement among the officers and scientists. Bessels, with Meyer's support, openly refused to follow Hall's orders for the scientific work. This disagreement spread to the crew, who were divided by their nationalities.

Tyson wrote in his diary that by the time they reached Disko Island, some people were saying Hall should not get any credit for the trip. He noted that some had already decided how far they would go and when they would return home. Hall asked Captain Henry Kallock Davenport of the supply ship USS Congress to help. Davenport threatened to put Meyer in chains for not following orders and send him back to the U.S. At this point, all the Germans threatened to quit. Hall and Davenport had to back down. But Davenport gave a strong speech to the crew about following rules.

In another sign of trouble, someone on the Polaris had damaged the ship's boilers. The special boilers that burned animal fat had disappeared. They seemed to have been thrown overboard. On August 18, the ship reached Upernavik on Greenland's west coast. There, they picked up Hendrik. The Polaris then sailed north through Smith Sound and the Nares Strait. It passed the furthest north records set by Kane and Hayes.

Hall's Sickness and Passing

By September 2, the Polaris had reached its furthest north point, 82° 29′ N. Tensions rose again because the three main officers could not agree on whether to go further. Hall and Tyson wanted to push north. This would shorten the distance they needed to travel to the Pole by dog sled. Budington did not want to risk the ship any more and left the discussion. In the end, the Polaris sailed into Thank God Harbor on September 10. It anchored there for the winter on the coast of northern Greenland.

Within a few weeks, Hall began preparing for a sled trip. He wanted to beat Parry's record for the furthest north. The lack of trust among the leaders showed again. Hall told Tyson, "I cannot trust [Budington]. I want you to go with me, but don't know how to leave him alone with the ship." Hall had complained about Budington's drinking. This became clear in the crew's statements after the expedition. With Tyson watching the ship, Hall took two sleds with first mate Chester and the native guides Ipirvik and Hendrik. They left on October 10.

The day after leaving, Hall sent Hendrik back to the ship. He needed to get some forgotten items. Hall also sent a note to Bessels. He reminded Bessels to wind the ship's clocks at the correct time every day. In his book Trial by Ice, Richard Parry suggested that this note from Hall, who had little formal education, might have bothered Bessels. Bessels had degrees from important universities. This was another example of Hall trying to control every small detail of the trip. Before he left, Hall gave Budington a long list of instructions for managing the ship. This probably did not sit well with a sailing master who had over 20 years of experience.

When they returned on October 24, Hall suddenly became sick after drinking a cup of coffee. His symptoms started with a stomach ache. The next day, he was vomiting and confused. Hall accused several people on the ship, including Bessels, of poisoning him. After these accusations, he refused medical help from Bessels. He would only drink liquids given directly by his friend Taqulittuq. Hall seemed to get better for a few days. He was even able to go up on deck. Bessels had asked Bryan, the ship's chaplain, to convince Hall to let the doctor see him. By November 4, Hall agreed, and Bessels started treating him again. Soon after, Hall's condition got worse. He vomited, was confused, and collapsed. Bessels said it was a stroke before Hall died on November 8. He was taken ashore and buried formally.

Trying for the North Pole

According to the rules from Navy Secretary Robeson, Budington took command of the expedition. Under his leadership, discipline got even worse. The valuable coal was being used up very quickly. In November, 6,334 pounds were burned, which was 1,596 pounds more than the month before. In December, it was close to 8,300 pounds.

It was clear that the ship's daily routine was falling apart. Tyson wrote in his diary, "There is so little regularity observed. There is no stated time for putting out lights; the men are allowed to do as they please; and, consequently, they often make nights hideous by their carousing, playing cards to all hours." For unknown reasons, Budington gave out the ship's firearms to the crew.

On January 1, 1872, Tyson wrote in his diary about a surprising idea that had been discussed. It was about trying to go further north the next summer. Tyson felt that Captain Hall would be upset in his grave to hear some of the talk. He wrote again on April 23, saying he and Chester agreed the idea was "monstrous" and had to be stopped. Writer Farley Mowat suggested that the officers might have been thinking about faking a trip to the Pole.

Whatever the plan was, an expedition to try for the Pole was sent out on June 6. Chester led the trip in a whaleboat. But the boat was crushed by ice just a few miles from the Polaris. Chester and his men walked back to the ship. They convinced Budington to give them the collapsible boat. With this boat and Tyson guiding another whaleboat, the men set out north again.

Meanwhile, the Polaris found open water and was looking for a way south. Budington did not want to spend another winter in the ice. He sent Ipirvik north with orders for Tyson and Chester to return to the ship at once. The men had to leave their boats and walk 20 miles back to the Polaris. Now, three of the ship's important lifeboats were lost. A fourth, the small scow, was crushed by ice in July because it was left out overnight. The expedition had failed in its main goal of reaching the North Pole.

Tyson's diary shows that he, Chester, and Bessels were among those who most wanted to keep pushing north. On August 1, he wrote sadly about the lost chances. He felt they could have gone much further north. Tyson was frustrated by his companions' lack of interest. He knew they might never get such a good chance again. He added, "Someone will some day reach the pole, and I envy not those who have prevented Polaris having that chance."

The Polaris is Lost and Journeys Home

With the main goal given up, the Polaris turned south for home. In Smith Sound, west of the Humboldt Glacier, it hit a shallow iceberg and got stuck. On the night of October 15, with an iceberg threatening the ship, Schumann reported that water was coming in. The pumps could not keep up. Budington ordered cargo to be thrown onto the ice to make the ship lighter. Men started throwing things overboard without much care. A lot of the thrown cargo was lost.

Some of the crew were on the ice around the ship that night. The ice then broke apart. When morning came, the group found themselves stuck on a large piece of ice. This group included Tyson, Meyer, six sailors, the cook, the steward, and all the Inuit. The stranded group could see the Polaris 8 to 10 miles away. But their attempts to get the ship's attention with a large black cloth did not work.

Resigned to their situation on the ice, the Inuit quickly built igloo shelters. Tyson estimated they had 1,900 pounds of food. They also had the ship's two whaleboats and two kayaks. One kayak was soon lost when the ice broke up again. Meyer thought they were drifting near Greenland and would soon be close enough to row to Disko Island. He was wrong; they were actually near Canada. This mistake caused the men to ignore Tyson's plans for saving food. The sailors soon broke up one of the whaleboats for firewood. This made it very hard to escape safely to land.

One night in November, the men ate a huge amount of their food. The group drifted over 1,800 miles on the ice floe for the next six months. They were rescued off the coast of Newfoundland by the whaler Tigress on April 30, 1873. All of them probably would have died if the skilled Inuit hunters Ipirvik and Hendrik had not been with them. They were able to hunt and kill seals many times.

On October 16, 1872, with the Polaris's coal running low, Budington decided to run the ship aground near Etah. They had lost much of their bedding, clothing, and food when it was thrown from the ship on October 12. The remaining 14 men were not in good shape to face another winter. They built a hut from wood saved from the ship. On October 24, they put out the ship's boilers to save coal. The pumps stopped working for good. The ship tipped over on its side, half out of the water. Luckily, the Etah Inuit helped the men survive the winter. After wintering ashore, the crew built two boats from salvaged wood. On June 3, 1873, the crew sailed south. They were seen and rescued by the whaler Ravenscraig in July. They returned home through Scotland.

What Happened Next

The Investigation

On June 5, 1873, a naval investigation began. At this time, the crew and Inuit families from the ice floe had been rescued. But no one knew what had happened to Budington, Bessels, and the rest of the crew. The board included Robeson, Admiral Louis M. Goldsborough, Commodore William Reynolds, Army Captain Henry W. Howgate, and Spencer Fullerton Baird from the Academy of Sciences.

Tyson was the first to be questioned. He spoke about the disagreements between Hall, Budington, and Bessels. He also mentioned Hall's accusations of poisoning before he died. The board also asked about Hall's diaries and records. Tyson said that while Hall was confused, he told Budington to burn some papers. The rest had disappeared. Later, diaries from other crew members were found at the Polaris wreck site. But the parts about Hall's death had been cut out. Meyer testified that Budington drank a lot.

Steward John Herron said he did not make the coffee that Hall thought was poisoned. He explained that the cook made the coffee. He had not kept track of how many people had touched the cup before it went to Hall. After Budington and the rest of the crew were rescued and returned to the U.S., the investigation continued. Budington argued against Tyson's statements. He denied that he had stopped Hall from sailing the ship further north. He also denied reports of his drinking, saying he "made it a practice to drink but very little."

Bessels was questioned about Hall's cause of death. He stated that Hall had been exposed to very cold temperatures during his sled journey. He came back and entered a warm cabin without taking off his heavy fur clothes. Then he drank a warm cup of coffee. Bessels said Hall had a stroke-like illness. He also said Hall's left arm and side were paralyzed. Bessels said he gave Hall quinine to lower his high temperature before he died.

The investigators faced confusing statements. There were no official records or diaries. And there was no body for an autopsy. So, no one was charged in connection with Hall's death. In the final report, the top doctors from the Army and Navy wrote that Hall died from natural causes, specifically a stroke. They also said that Dr. Bessels' treatment was the best possible given the situation. However, in 1968, Hall's body was examined. It was found that he had a large amount of arsenic in his body when he died. This finding suggested that he had been poisoned.

See also

In Spanish: Expedición Polaris para niños

In Spanish: Expedición Polaris para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |