Prehistoric agriculture in the Southwestern United States facts for kids

The Native Americans living in the Southwestern United States (like Arizona and New Mexico) were very clever farmers. This region doesn't get much rain, so they had to find smart ways to grow food. They used irrigation (bringing water to fields) and special methods to collect and save rainwater.

To make the most of the limited water, they built irrigation canals, terraces (called trincheras), used rocks as mulch, and farmed in floodplains. Being good at farming allowed some groups to live in large communities with thousands of people. Before this, they were hunter-gatherers living in small groups of only a few dozen.

Maize (corn) was their most important crop. It came from Mesoamerica (modern-day Mexico and Central America). People started growing it in the Southwest around 2100 BCE. Because of farming, cultures like the Hohokam, Mogollon, Ancestral Puebloans, and Patayan settled down and grew.

Farming in the Southwest was tough. Many successful farming societies eventually changed or disappeared. But they left behind amazing clues about their lives. Some groups, like the Pueblos in the U.S. and the Yaqui and Mayo in Mexico, were very strong and still exist today.

First Farmers in the Southwest

Even though people might have grown some native plants like gourds and chenopods very early, the first clear sign of corn farming in the Southwest is from about 2100 BCE. Scientists have found small, old corn cobs at five different places in New Mexico and Arizona. These places are very different, from the desert near Tucson (low and hot) to a rocky cave on the Colorado plateau (high and cool). This shows that the early corn they grew could already handle both hot, dry places and places with short growing seasons.

Corn traveled to the Southwest from Mexico, but we don't know the exact path. It spread quite quickly. One idea is that farmers speaking a Uto-Aztecan language moved north from central Mexico, bringing corn with them. Another idea, which many experts now believe, is that corn seeds were simply traded and passed from one group to another, rather than people moving.

The first time corn was grown in the Southwest was during a time when there was more rain. Even though corn farming spread fast, the hunter-gatherers living there didn't immediately rely on it for all their food. Instead, they added corn farming to their hunting and gathering. Hunter-gatherers usually eat many different kinds of food. This way, if one food source fails, they still have others.

Before farming, hunter-gatherer groups were usually small, with only 10 to 50 people. Sometimes, several groups would meet for special events. As corn farming became more important, communities grew bigger and stayed in one place. But hunting and gathering wild foods were still important. Some farming towns, like Casa Grande and Casas Grandes, or Pueblo and Opata settlements, might have had over 2,000 people at their busiest times. Many more lived in smaller villages of 200 to 300 people, or in isolated homes.

It's interesting that corn farming started in the Southwest much earlier than in the eastern United States, even though the eastern U.S. has a much better climate for farming.

What They Grew

Early farmers in the Southwest probably started by helping wild plants like amaranth and chenopods grow. They also grew gourds for their seeds and to use as containers. The first corn grown in the Southwest was a type of popcorn with cobs only about one or two inches long. It didn't produce much food. Over time, farmers in the Southwest developed better types of corn, or new ones were brought from Mesoamerica.

Beans and squash also came from Mesoamerica. But the Tepary bean, which can handle dry weather, was native to the Southwest. Cotton was likely grown around 1200 BC in the Tucson area. There's also evidence of tobacco use, and maybe even growing it, around the same time.

Agave, especially a type called Agave murpheyi, was a very important food for the Hohokam people. They grew it on dry hillsides where other crops couldn't survive. These early farmers also ate and might have helped grow cactus fruit, mesquite beans, and wild grasses for their edible seeds.

Farming Tools

Southwestern Native Americans didn't have animals to help them farm, and they didn't have metal tools. They planted seeds using a sharpened stick, often hardened by fire. This tool is now called a dibble stick. Hoes and shovels were made from wood or the shoulder bones of large animals like buffalo. Mussel shells, pottery pieces, and rocks were also used for planting and digging.

Farmers usually didn't use animal waste to fertilize their fields. Instead, they rotated crops (grew different things in the same spot each year), let fields rest, and used the rich silt left behind by rainwater runoff. Sometimes, they would burn land to clear it and add ash to the soil. They carried water in large pottery jugs to water small garden plots by hand.

Smart Water Use

Farming in the lower parts of the Southwest is very hard without irrigation because there's so little rain. Higher up, around 5,000 feet (1,500 m), there might be more rain, but it's also colder, has shorter growing seasons, and the soil isn't as good. Either way, farming was a big challenge. Ancient Southwestern farmers used many strategies: choosing the best seeds, letting fields rest, planting in different places, planting at different times, and growing different types of corn and beans separately.

Canal Irrigation

The Las Capas site near Tucson has the oldest irrigation system found in North America, dating back to 1200 BCE. This network of canals and small fields (each about 250 square feet or 23 square meters) covers over 100 acres (40 hectares). This shows that a large community of people worked together on big projects. Tobacco pipes, the oldest ever found, were also discovered there. This site might have supported 150 people. The corn grown at Las Capas was similar to today's popcorn. Archaeologists think the kernels were popped and then ground into flour for tortillas.

The Las Capas people were likely the ancestors of the Hohokam, who were the most skilled farmers in the Southwest. The Hohokam lived in the Gila and Salt river valleys of Arizona between the first century and 1450 CE. Their society grew strong around 750 CE, probably because they were so good at farming.

The Hohokam built a huge system of canals to water thousands of acres of farmland. Their main canals were up to 10 meters (10 yards) wide and 4 meters (4 yards) deep. They stretched across the river valleys for as much as 30 kilometers (19 miles). At their peak in the 14th century, there might have been 40,000 Hohokam people.

The sudden disappearance of the Hohokam between 1400 and 1450 CE is a mystery. Archaeologists guess that keeping the canals working was hard, and dirt built up over hundreds of years. Farmers had to leave old canals and move further from the river, making farming even harder. After a thousand years of success, the Hohokam couldn't keep up their intense farming system. They vanished from the archaeological record. When Spanish explorers arrived in the Gila and Salt valleys in the 16th century, only a few Pima and Tohono O'odham (Papago) Indians lived there. These groups are likely the descendants of the Hohokam.

After the Hohokam disappeared, Spanish explorers in the 16th century saw canal irrigation only in two areas: eastern Sonora (used by the Opata and Lower Pima) and among the Pueblos of northern New Mexico. The Opata and Pueblos used irrigation for different reasons. In Sonora, with a long growing season, they grew two corn crops a year in river valleys. The spring crop during the dry season needed irrigation. The summer and fall crop during the rainy season used irrigation to help the rain. This need for irrigation probably required a lot of teamwork and organization in their society. In New Mexico, where only one corn crop was possible each year, irrigation was just extra help. This meant they didn't need as much social organization as in Sonora.

Trincheras (Terraces)

Trincheras (which means "trenches" or "fortifications" in Spanish) are rock walls or terraces built on hillsides by ancient Native Americans. Trincheras are found all over the Southwest. They date back to almost the very beginning of farming in the region. Around 1300 BCE, at Casas Grandes in Chihuahua, early farmers built hill forts and trincheras on hillsides. These big projects needed a lot of work and organization, showing that the communities were settled and had many people.

Trincheras had several uses, like defense, places for homes, and farming. For farming, they created flat planting areas, helped stop soil from washing away, collected and managed water, and protected plants from frost damage. Farming on hillsides with trincheras was often less important than farming in floodplains. Trincheras were probably used to grow all kinds of crops. Southwestern Indian farmers often grew different crops in several different fields and environments. This helped them reduce the risk of crop failure. If one planting failed, others might still succeed.

Four main types of trincheras were built. Check dams were built across natural water paths to catch rainwater runoff. Terraces and linear borders were built along the curves of hills to create flat planting areas or home sites. Near permanent streams and rivers, riverside terraces were built to catch floodwaters. Trincheras were very widespread. For example, archaeologists have found 183 upland farming spots near Casas Grandes with trincheras that add up to nearly 18 miles (26,919 meters) in length. This wide use of trincheras at Casas Grandes was also seen in many other farming societies in the Southwest.

Rock Mulch

Using rocks or cobbles as a mulch was another farming technique in the Southwest. Rocks were placed around growing plants and in fields. The rocks acted like a blanket, helping the soil hold moisture, reducing soil erosion, controlling weeds, and making the nighttime temperatures warmer by absorbing and releasing heat.

In the 1980s, archaeologists found that large areas of agave, especially Agave murpheyi, had been grown in rock mounds by the Hohokam in the Tucson Basin, near the city of Marana. Since then, 78 square kilometers (almost 20,000 acres) of old agave fields have been found, mostly between Phoenix and Tucson. Many other fields have likely been destroyed or haven't been found yet. Northern New Mexico also has the remains of many fields that used rock mulch. Corn and cotton pollen have been found in the soil linked to these rock mounds and mulch.

Floodplain Farming

To make sure they had enough food, Southwestern Native Americans also farmed the floodplains of rivers and temporary streams. Crops were planted in these areas and on islands to use the high water when the river or stream overflowed. This soaked the land with water and made the soil richer with silt. This method worked best when floods happened at regular times.

Floodplain farming was used instead of canal irrigation by the La Junta Indians (often called Jumano) along the Rio Grande in western Texas. Other groups used it too.

The semi-nomadic Tohono O'odham and other Native Americans of the Sonoran Desert practiced a type of farming called ak-chin for the native tepary bean (Phaseolus acutifolius). In this very dry desert, after summer monsoon rains, the Papago people would quickly plant tepary beans in small areas where a stream or dry riverbed had overflowed and soaked the soil. The tepary bean grew fast and ripened before the soil dried out. The Native Americans often managed the flow of floodwater to help the beans grow.

Floodplain farming was possible even in the toughest conditions. The Sand Papago (Hia C-eḍ O'odham) were mostly hunter-gatherers, but they farmed floodplains when they could. In 1912, a researcher named Carl Lumholtz found small cultivated fields, mainly of tepary beans, in the Pinacate Peaks area of Sonora. In the Pinacate, which gets only about three inches (75mm) of rain a year and has temperatures up to 118°F (48°C), Papago and Mexican farmers used runoff from the sparse rains to grow crops. In the 1980s, author Gary Paul Nabhan visited this area. He found one farm family taking advantage of the first big rain in six years, planting seeds in the wet ground, and harvesting a crop two months later. The most successful crops were tepary beans and a type of squash that could handle drought. Nabhan figured out that the Pinacate is the driest place in the world where farming is done only with rain.

What Happened to the Farmers?

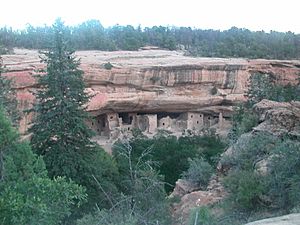

The Southwest is full of old ruins from Native American societies that tried to farm in this challenging region. The Ancestral Puebloan centers of Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde were left empty in the 12th and 13th centuries CE, probably because of long droughts. After a thousand years of success, the complex Hohokam society disappeared in the 15th century CE. They became the smaller Pima culture we know from more recent history.

However, many Native American farming societies have been incredibly strong and lasted a long time. The Rio Grande Pueblos, the Hopi, and the Zuni have survived to this day, keeping much of their traditional culture. Many Mexican Native Americans have blended into a mestizo society, but the Yaqui and Mayo still keep their unique identities and part of their traditional lands. The once numerous Opata have disappeared as a distinct group, but their descendants still live in the valleys of the Sonora River and its smaller rivers.

See also

In Spanish: Agricultura en el suroeste de Estados Unidos prehistórico para niños

In Spanish: Agricultura en el suroeste de Estados Unidos prehistórico para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |