False killer whale facts for kids

Quick facts for kids False killer whaleTemporal range: Middle Pleistocene–Recent

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Pseudorca

|

| Species: |

crassidens

|

|

|

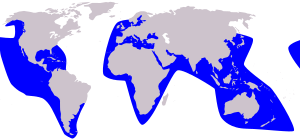

| Range of the false killer whale | |

| Synonyms | |

False killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens) are cetaceans and larger members of the oceanic dolphin family (Delphinidae). The species is the only member of the Pseudorca genus.

They live in temperate and tropical waters throughout the world. As its name implies, the false killer whale shares characteristics with the more widely known Orca ("killer whale"). The two species look somewhat similar and, like the orca, the false killer whale attacks and kills other cetaceans. However, the two dolphin species are not closely related.

The false killer whale has not been extensively studied in the wild by scientists; much of the data has been obtained by examining stranded animals.

Contents

Population and distribution

The false killer whale appears to have a widespread, if small, presence in tropical and semitropical oceanic waters. A few have been found in temperate water, but these are probably stray individuals. Their most common habitat is the open ocean, though they also frequent other areas. They have been sighted in fairly shallow waters such as the Mediterranean Sea and Red Sea, as well as the Atlantic Ocean (from Scotland to Argentina), the Indian Ocean (in coastal regions and around the Lakshadweep Islands), the Pacific Ocean (from the Sea of Japan to New Zealand and the tropical area of the eastern side), and in Hawaii. Recently, a pod of false killer whales was observed hunting down a small species of shark in Australia.

The Hawaiian populations are the most studied groups of false killer whales. The three distinct groups in the islands are an offshore population, a northwestern Hawaiian Island group, and a small group around the main Hawaiian Islands. This last group, a unique, small, insular population, is genetically distinct from the other populations.

A false killer whale and a bottlenose dolphin mated in captivity and produced a fertile calf. The hybrid offspring has been called a “wholphin”.

Description

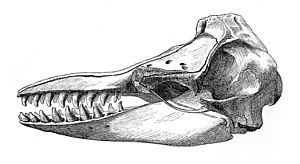

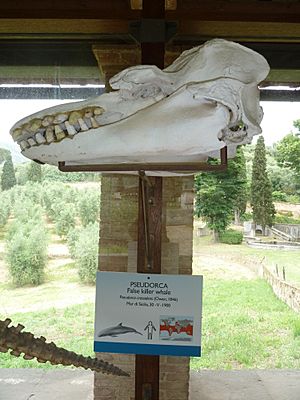

The false killer whale is black with a grey throat and neck. It has a slender body with an elongated, tapered head and 44 teeth. The dorsal fin is sickle-shaped and its flippers are narrow, short, and pointed. The average size is around 4.9 m (16 ft). Females can reach a maximum known size of 5.1 m (17 ft) in length and 1,200 kg (2,600 lb) in weight, while the largest males can reach 6.1 m (20 ft) and as much as 2,200 kg (4,900 lb).

Human interaction

False killer whales are kept in captivity and studied in the wild by scientists. Several public aquaria display them. For example, Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium in Japan displays false killer whales in the Okichan Theater.

These whales have been known to approach and offer fish they have caught to humans diving or boating.

Scientists have undertaken research to understand more about the species—including population surveys, satellite-tagged individual whales, and carcass studies. From these studies, they determined information about habitat, range, and distinct populations. Recent study of the local population of false killer whales in Hawaii shows evidence of a dramatic decline over the last 20 years. Five years of aerial surveys from 1993 through 2003 show a steep decline in sighting rates. Group sizes of the largest groups documented before 1989 surveys were almost four times larger than the entire 2009 population estimate.

Beachings

On July 30, 1986, a pod of 114 false killer whales became stranded at Town Beach, Augusta, in Flinders Bay, Western Australia. In a three-day operation, coordinated by the Department of Conservation and Land Management, volunteers carried 96 of the whales on trucks to more sheltered waters, and then successfully guided them out into the bay.

On June 2, 2005, up to 140 (estimates vary) false killer whales were beached at Geographe Bay, Western Australia. The main pod, which had split into four strandings along the length of the coast, was successfully moved back to sea, with only one death, after 1,500 volunteers intervened, coordinated once again by the Department of Conservation and Land Management.

Just before sunrise on May 30, 2009, a pod of 55 false killer whales was discovered stranded on a sandy beach at Kommetjie in South Africa (34°8′3.98″S 18°19′58.22″E / 34.1344389°S 18.3328389°E). Despite the efforts of over 50 volunteers, most animals beached themselves again and the weather complicated further attempts. Authorities euthanized 44 whales.

As of July 2014, no record of an orphaned infant of the species surviving to adulthood after stranding has been reported, but veterinarians expressed hope about the prospects of a six-week-old male calf found on the shores of North Chesterman beach, near Tofino, British Columbia. He was found in critical condition on 11 July 2014, and received care at the Vancouver Aquarium.

On January 14, 2017, an estimated 95 individuals beached themselves on a remote mangrove beach in mainland Monroe County, Florida, in the western Everglades National Park. This was the largest stranding of false killer whales in recorded Florida history. At least 81 died and others disappeared during the night. Two other strandings of false killer whales have been recorded in Florida. The first was in 1986 when 28 false killer whales beached near Key West. Three years later, 40 individuals beached off Cedar Key.

Images for kids

-

False killer whale breaching

-

Mar del Plata in Argentina in 1946, the largest false killer whale stranding

-

The Flinders Bay beaching in 1986

See also

In Spanish: Falsa orca para niños

In Spanish: Falsa orca para niños