Raising the Flag at Fort Sumter facts for kids

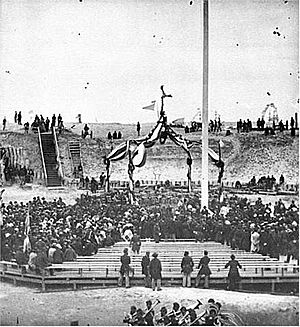

The event known as Raising the Flag at Fort Sumter was a special ceremony. It happened at Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, on April 14, 1865. This was almost exactly four years after the Fort Sumter Flag was taken down at the start of the American Civil War. Just a few days before, on April 9, General Lee had surrendered, marking the end of the war. This ceremony was meant to celebrate the Union victory and the end of the long conflict.

However, this important event was quickly forgotten. That same evening, April 14, President Lincoln was shot. News reports about the flag ceremony and Lincoln's shooting sometimes appeared on the same newspaper page. This tragic event overshadowed the celebration at Fort Sumter.

Contents

- The Flag Comes Down: April 13, 1861

- The Flag's Journey as a Symbol

- Charleston Returns to Union Control: February 1865

- Nationwide Celebrations Begin

- Choosing April 14 for the Ceremony

- Bright Lights: Lincoln's Speech on April 11

- Washington D.C. Lights Up: April 13

- The Big Day: April 14, 1865

- Images for kids

The Flag Comes Down: April 13, 1861

The attack on Fort Sumter by South Carolina forces on April 12, 1861, is often seen as the beginning of the American Civil War. The Southern states, which had formed the Confederacy, wanted Union troops out of their territory. Fort Sumter was a key Union outpost in the South. The Union refused to leave. It was clear that fighting would start there.

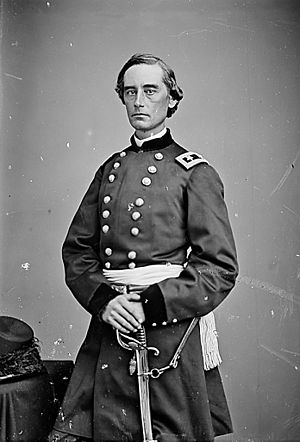

The South Carolinians fired first. People in Charleston watched the attack from the city. When the Union soldiers surrendered and left Fort Sumter on April 13, their commander, Major Robert Anderson, took the damaged flag with him.

The Flag's Journey as a Symbol

Major Anderson brought the Fort Sumter flag to New York City. On April 20, 1861, it was displayed at a patriotic rally. More than 100,000 people gathered in Union Square. This was one of the largest public gatherings in the country at that time.

The flag was carefully kept in a small wooden box. It traveled from town to town in the North to help raise money for the Union cause. It was shown at many patriotic events and became a well-known symbol of Union pride.

Charleston Returns to Union Control: February 1865

On February 18, 1865, Confederate forces left Charleston. They set fire to thousands of cotton bales, which caused fires to spread to buildings. The first job for the Union troops was to help put out these fires. Newspaper reports said that the flag General Anderson had taken down four years earlier was raised again.

On February 22, the New York Chamber of Commerce asked President Lincoln to send Major General Robert Anderson back to Fort Sumter. They wanted him to be the one to raise the flag again.

Nationwide Celebrations Begin

The end of the war was clear to everyone. Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy, fell on April 2. Celebrations started all over the North.

On April 8, a group of merchants in New York asked President Lincoln for a "National Thanksgiving Day." They wanted a day to celebrate the Union's victories and show thanks to General Grant and the soldiers.

Plans for a ceremony at Fort Sumter on April 14 were already being made. The ship Arago sailed from New York to Charleston on April 8. It carried General Anderson and the old Fort Sumter flag. The plan was for Sergeant Peter Hart, who had raised the flag in 1861 after it was shot down, to raise it again.

On April 9, General Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House. This was widely seen as the official end of the war.

Choosing April 14 for the Ceremony

President Lincoln never officially declared a national thanksgiving day. However, the governors of several states chose April 14 as a day of thanksgiving. The Governor of New York, Reuben Fenton, declared April 14 (the day the flag was to be raised at Fort Sumter) as a day for prayer and thanks.

The Governor of Ohio, John Brough, suggested a more public celebration. He recommended that April 14 be a day of thanks and rejoicing, with religious gatherings, bonfires, fireworks, speeches, and other ways to celebrate the army's heroic actions and the return of peace.

There was a small mix-up because the four-year anniversary was actually April 13, not April 14. Also, April 14 was Good Friday, a religious holiday. Some people thought it was not a good day for celebrations. However, Henry Ward Beecher, a famous minister, pointed out that Good Friday was also a day of resurrection. So, the celebrations went ahead on April 14.

Bright Lights: Lincoln's Speech on April 11

"Illumination" meant lighting up buildings with bright lights. In 1865, electric lights didn't exist yet. People used gas lights, which were new and impressive. Seeing large buildings like the U.S. Capitol or the White House brightly lit at night was amazing. These bright lights also allowed happy crowds to gather in the streets for parades.

On April 11, President Lincoln spoke at the White House to a huge crowd under these bright lights. He talked about giving voting rights to African American men, especially those who were intelligent or had served as soldiers.

John Wilkes Booth, who was planning to harm Lincoln, heard this speech. He reportedly said, "That is the last speech he'll ever make."

Washington D.C. Lights Up: April 13

On Thursday, April 13, Washington D.C. was lit up. The White House, Capitol, and many other government buildings were illuminated. Many citizens also decorated their homes.

Newspapers reported that the city was "ablaze with glory." Streets were bright with patriotic lights. Words like "Union," "Victory," and the names of famous generals like Grant, Sheridan, and Sherman were displayed in lights. There were also loud music and cheers. The Washington Evening Star newspaper dedicated its entire front page to describing the amazing illuminations across the city.

The Big Day: April 14, 1865

Raising the Flag in Charleston

A group of 180 people, including many from Reverend Beecher's church, sailed from New York to Charleston. They arrived on April 13 and shared the joyful news of Lee's surrender. Many other boats filled with visitors also arrived.

On Friday, April 14, many people traveled to Fort Sumter. A new dock had been built there. A fleet of boats, including the famous USS Planter led by Robert Smalls (a former enslaved person who had bravely taken the ship from the Confederates), carried Black residents and visitors to the celebration.

Now-Major General Anderson, even though he was ill and retired, returned to Fort Sumter to raise the flag. Henry Ward Beecher, the country's most famous minister, gave the main speech at the event. He spoke about the end of the war and the strength the nation had gained. He said, "Rebellion has perished, but there flies the same flag that was insulted."

Wm. Lloyd Garrison, who published an anti-slavery newspaper called The Liberator, also took part in the ceremony.

That evening, a ball was held in Charleston by General Hatch's staff. It was held in the same hall as a ball given by General Beauregard four years earlier, right after the fort surrendered. They even used the same caterer and dishes!

Celebrations Elsewhere

In Washington D.C., there was a torchlight parade with about 2,000 people. It went to the White House and then to the home of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, who spoke to the crowd. There were bands, cannons, and fireworks.

In Columbus, Ohio, the "Union celebration" began at 6 AM with 100 gun salutes, repeated at noon and 6 PM. Speeches, a torchlight parade, and fireworks followed. In Bellows Falls, Vermont, people were so excited that they rang the church bell loudly, cheering for the Union.

In Bangor, Maine, the "Stars and Stripes" flag was flown 1,000 feet over the city using kites. One large kite read "U.S. Grant."

In Philadelphia, African American people had a parade and gave a flag to the Twenty-fifth Regiment of the United States Colored Troops.

President Lincoln's Assassination

Around 10:25 PM on April 14, President Lincoln was shot at Ford's Theatre by John Wilkes Booth. Lincoln never woke up and died the next morning. Booth had planned to attack several leaders. An accomplice, Louis Powell, attacked and seriously hurt Secretary of State William H. Seward and two of his sons. Another conspirator was supposed to attack Vice President Johnson, but he did not.

Images for kids

-

Colored soldiers singing "John Brown's Body" as they marched into Charleston, South Carolina, in February of 1865

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |