John Brown's Body facts for kids

"John Brown's Body" (also known as "John Brown's Song") is a famous United States marching song. It is about John Brown, a person who fought to end slavery. This song was very popular with the Union soldiers during the American Civil War.

The tune for the song came from old American folk music and church songs. These songs were often sung at outdoor church gatherings called "camp meetings" in the late 1700s and early 1800s. People say the first lyrics for "John Brown's Body" were made up by Union soldiers. They were singing about the famous John Brown, but also joking about a sergeant in their own group who was also named John Brown.

Many people felt the first words were a bit rough or disrespectful. So, new versions of the song were created with more serious and poetic words. The most famous new version is "Battle Hymn of the Republic" by Julia Ward Howe. She wrote it after someone suggested she create better words for the exciting tune.

Over the years, many different versions of the song have been made. This shows how "John Brown's Body" is a living folk music tradition, always changing and adapting.

Contents

The Tune's Journey: How It Grew

The tune that became "John Brown's Body" and the "Battle Hymn of the Republic" started as a song called "Say, Brothers, Will You Meet Us." It was sung at American camp meetings in the late 1700s and early 1800s.

These meetings were held in wilder areas where people didn't often go to church. They would gather to worship with traveling preachers. These events were important for people to meet, but they were also known for being very lively and sometimes wild.

In these meetings, hymns were learned by listening and repeating. People often made up new parts of songs on the spot. This is how folk music changes over time.

People who study American religious history say that camp meeting music was created by the people attending. When they felt moved by a sermon or prayer, they would take lines from the preacher. They would then use these lines to start a short, simple tune. This tune was either borrowed from another song or made up right there. The line would be sung many times, changing a little each time. Slowly, it would become a verse that others could easily learn and remember.

Early versions of "Say, Brothers" had lines like:

Oh! Brothers will you meet me

Oh! Sisters will you meet me

Oh! Mourners will you meet me

Oh! Sinners will you meet me

Oh! Christians will you meet me

This first line was sung three times, then finished with "On Canaan's happy shore."

The first choruses included lines such as:

We'll shout and give him glory (3×)

For glory is his own

The famous "Glory, glory, hallelujah" part of the song grew from these camp meeting traditions. This happened sometime between 1808 and the 1850s.

Songs like "Say, Brothers" were mostly passed down by people singing them, not by being written down. But it was printed in songbooks as early as 1806–1808 in places like South Carolina and Massachusetts.

The tune was popular in southern camp meetings with both African-American and white churchgoers. It spread through Methodist and Baptist church groups. By 1861, many different groups, including Baptists and Mormons, were using "Say Brothers" as their own song.

For example, in 1858, a song called "My Brother Will You Meet Me" was published. It had the music but not the words of the "Glory Hallelujah" chorus.

Some people think the tune came from an African-American folk song or a British sea shanty. It's hard to know for sure because the tune was passed down by singing. But it's clear that many different folk music styles influenced the songs sung at camp meetings.

It's thought that "Say Brothers, Will You Meet Us" might have had a hidden meaning about ending slavery. "Canaan's happy shore" could have meant a better, free place. This idea became much stronger when the "John Brown" lyrics were added, linking the song to the famous abolitionist and the Civil War.

The Song During the Civil War

In 1861, a new group of soldiers, the 29th New York Infantry Regiment, was in Charles Town, Virginia. This was where John Brown had been executed. Soldiers would visit the spot every day, singing a song that included:

May heaven's smiles look kindly down

Upon the grave of old John Brown."

Frederick Douglass, a friend of John Brown, said:

He [John Brown] was with the troops during that war. He was seen in every camp fire. Our boys pressed onward to victory and freedom, timing their feet to the stately stepping of Old John Brown as his soul went marching on.

At Andersonville Prison, a place where Union soldiers were held captive, a Confederate soldier described hearing the song. He said:

I cannot tell the horror of that scene. It was almost sundown of a hot autumn day. The sadness on the faces of that poor, unprotected crowd was beyond words. I could hear the wind in the pine trees, but they had no air or shade. The smell, even where I stood, was sickening. Because I had been a prisoner myself, I felt even more sorry for them. I could guess what they had to suffer, though I only partly imagined the terrible things they faced. As I turned away, I heard singing from the sad crowd. I stopped and listened—listened to the very end of that amazing song of sacrifice. It was a song that inspired an army and a people to suffer and achieve for others. When I left in the evening, the words stayed with me and I have never forgotten them.

In the beauty of the lilies Christ was born across the sea

With a glory in His bosom that transfigures you and me;

As He died to make men holy, let us die to make men free.This song is an anthem that is more powerful than all patriotic songs from Miriam's time until now. It shows the highest level of human devotion. 'Perhaps for a good man some would even dare to die,' is the most extreme idea of human sacrifice. But from that hot, smelly prison, into the quiet night, came the wonderful singing of hundreds. They were facing a slow and terrible death. 'As He died to make men holy, let us die to make men free!'

The Song's Reach: Beyond the War

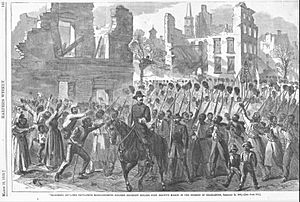

On May 1, 1865, in Charleston, South Carolina, newly freed African-Americans and some white missionaries held a parade. Ten thousand people marched, led by 3,000 Black children singing "John Brown's Body." This march honored 257 Union soldiers who had died and were reburied from a mass grave. This event is seen as the first celebration of Decoration Day, now known as Memorial Day.

In 1906, an American official in Vladivostok, Russia, reported that Russian soldiers were singing the song. This was during the 1905 Russian Revolution.

How the "John Brown's Body" Words Were Written

First Public Performance

The "John Brown" song was likely played in public for the first time on May 12, 1861. This was at a flag-raising event at Fort Warren, near Boston. The American Civil War had started the month before.

Newspapers reported that soldiers were singing the song as they marched in Boston on July 18, 1861. Many printed copies of the song with similar words quickly appeared.

"Tiger" Battalion Creates the Lyrics

In 1890, George Kimball wrote about how the 2nd Infantry Battalion of the Massachusetts militia, called the "Tiger" Battalion, created the words to "John Brown's Body." Kimball explained:

We had a cheerful Scottish man in the battalion named John Brown... and since he had the exact same name as the old hero of Harper's Ferry, his friends immediately started teasing him. If he showed up a few minutes late for work, or was a bit slow to get in line, he would surely be greeted with things like "Come, old fellow, you should be working if you're going to help us free the slaves"; or, "This can't be John Brown—why, John Brown is dead." And then someone would add, in a serious, slow voice, as if to really make it clear that John Brown was truly, actually dead: "Yes, yes, poor old John Brown is dead; his body lies mouldering in the grave."

Kimball said these sayings became common among the soldiers. Then, like the camp meeting songs, they slowly put these sayings to the tune of "Say, Brothers":

Finally, silly, rhyming songs about John Brown being dead and his body decaying began to be sung to the hymn's music. These songs changed in many ways until they reached the lines—

John Brown's body lies a-mouldering in the grave,

His soul's marching on.And,—

He's gone to be a soldier in the army of the Lord,

His soul's marching on.These lines seemed to please everyone. The idea that Brown's soul was "marching on" was immediately seen as inspiring. They were sung over and over with great enthusiasm, always adding the "Glory hallelujah" chorus.

Some leaders in the battalion thought the words were too rough. They tried to get the soldiers to sing more proper lyrics, but it didn't work. Members of the battalion, with publisher C. S. Hall, soon prepared the lyrics for printing. They chose and improved verses and might have even asked a local poet for help.

Other People Claiming to Be the Author

Many people claimed to have written the "John Brown Song" when it was very popular in the late 1800s.

- William Steffe: Some hymnals say William Steffe wrote the tune. Steffe himself said he wrote it around 1855 or 1856 for a fire company. However, the "Glory Hallelujah" tune and "Say, Brothers" words were around decades before he was born.

- Thomas Brigham Bishop: Maine songwriter Thomas Brigham Bishop also claimed to have created the song. He also said he wrote other famous songs like "When Johnny Comes Marching Home."

Since the tune was used in camp meetings in the late 1700s and early 1800s, long before most of these people were born, it's clear that none of them actually wrote the original tune.

As Annie J. Randall wrote, "Many authors, most of them unknown, borrowed the tune from 'Say, Brothers,' gave it new words, and used it to celebrate Brown's fight to end slavery." This way of constantly reusing and changing existing words and tunes is a key part of folk music. People didn't mind if others used their folk songs. Those who claimed to have written the tune might have helped create some of the new versions, but they likely wanted the fame that came with such a well-known song.

New Versions of the Song

Once "John Brown's Body" became a popular marching song, more formal versions of the lyrics were written. For example, William Weston Patton wrote his version in October 1861. It was published in the Chicago Tribune.

Other versions include the "Song of the First of Arkansas" and "The President's Proclamation." This last one was written in 1863 when the Emancipation Proclamation was announced.

Other Songs Using the Same Tune

The tune of "John Brown's Body" has been used for many other songs:

- "The Battle Hymn of the Republic": This famous song was directly inspired by "John Brown's Body."

- "Blood on the Risers": A World War II song with the chorus "Glory, glory (or Gory, gory), what a hell of a way to die/And he ain't gonna jump no more!"

- "Solidarity Forever": This is one of the most famous labor union songs in the United States. It became an anthem for unions fighting for workers' rights.

- Sea shanty: Sailors adapted "John Brown's Body" into a Capstan Shanty, sung while raising the anchor.

- Children's songs: Many playful versions have been created. "The Burning of the School" is a well-known parody sung by schoolchildren. Another version starts "John Brown's baby has a cold upon his chest."

- Football chants: It's often used as a football chant, generally called Glory Glory.

- International versions:

* French paratroopers sang a version: "oui nous irons tous nous faire casser la gueule en coeur / mais nous reviendrons vainqueurs" (meaning "yes, we'll get our skulls broken together / but we'll come back victorious"). * In Sri Lanka, it was adapted into a song sung at cricket matches. * A German children's song, "Alle Kinder lernen lesen" ("All Children Learn to Read"), uses the music.

Song Lyrics: How They Changed

The words used with the "John Brown" tune generally became more complex. They started as simple camp meeting songs, then became marching songs, and finally more literary versions.

As more syllables were added to the words, the melody had to change to fit them. This made the verse and chorus, which were musically the same in "Say, Brothers," sound very different in "John Brown's Body."

This trend continued in later versions and in the "Battle Hymn of the Republic." These songs have many more words per verse. The extra words are fit in by adding more rhythmic changes to the melody. Also, they include four separate lines in each verse instead of repeating the first line three times. This made the verse and chorus even more different in rhythm and poetry, even though the basic tune was still the same.

"Say, Brothers" Lyrics

(1st verse)

Say, brothers, will you meet us (3×)

On Canaan's happy shore.

(Refrain)

Glory, glory, hallelujah (3×)

For ever, evermore!

(2nd verse)

By the grace of God we'll meet you (3×)

Where parting is no more.

(3rd verse)

Jesus lives and reigns forever (3×)

On Canaan's happy shore.

"John Brown's Body" Lyrics (1861 Versions)

John Brown's body lies a-mouldering in the grave; (3×)

His soul is marching on!

(Chorus)

Glory, glory, hallelujah! Glory, glory, hallelujah!

Glory, glory, hallelujah! his soul is marching on!

He's gone to be a soldier in the army of the Lord! (3×)

His soul is marching on!

(Chorus)

John Brown's knapsack is strapped upon his back! (3×)

His soul is marching on!

(Chorus)

His pet lambs will meet him on the way; (3×)

They go marching on!

(Chorus)

They will hang Jeff Davis to a sour apple tree! (3×)

As they march along!

(Chorus)

Now, three rousing cheers for the Union; (3×)

As we are marching on!

William Weston Patton's Version

William Weston Patton, a leader in the movement to end slavery and a pastor, wrote his "The New John Brown Song" in late 1861. It was published in the Chicago Tribune on December 16, 1861:

Old John Brown's body lies a moldering in the grave,

While weep the sons of bondage whom he ventured all to save;

But though he sleeps his life was lost while struggling for the slave,

His soul is marching on.

Glory Hallelujah!

John Brown was a hero, undaunted, true and brave,

And Kansas knew his valor when he fought her rights to save;

And now, though the grass grows green above his grave,

His soul is marching on.

(Chorus)

He captured Harper's Ferry, with his nineteen men so few,

And frightened "Old Virginny" till she trembled through and through

They hung him for a traitor, themselves a traitorous crew,

But his soul is marching on.

(Chorus)

John Brown was John the Baptist of the Christ we are to see --

Christ who of the bondmen shall the Liberator be,

And soon throughout the Sunny South the slaves shall all be free,

For his soul is marching on.

(Chorus)

The conflict that he heralded he looked from heaven to view,

On the army of the Union with its flag red, white and blue.

And heaven shall ring with anthems o'er the deed they mean to do,

For his soul is marching on.

(Chorus)

Ye soldiers of Freedom, then strike, while strike ye may,

The death blow of oppression in a better time and way,

For the dawn of old John Brown has brightened into day,

And his soul is marching on.

(Chorus)

See also

In Spanish: John Brown's Body para niños

In Spanish: John Brown's Body para niños

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |