Richard E. Byrd facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Richard E. Byrd

|

|

|---|---|

Byrd in 1928

|

|

| Birth name | Richard Evelyn Byrd Jr. |

| Born | October 25, 1888 Winchester, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | March 11, 1957 (aged 68) Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1912–1927 1940–1947 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | World War I World War II |

| Awards | Medal of Honor Navy Cross Navy Distinguished Service Medal Distinguished Flying Cross Legion of Merit Congressional Gold Medal |

| Spouse(s) |

Marie Donaldson Ames

(m. 1915) |

Rear Admiral Richard Evelyn Byrd Jr. (October 25, 1888 – March 11, 1957) was an American naval officer and explorer. He was known for his amazing flights over the North Pole and South Pole. He also helped plan important trips across the Atlantic Ocean. Byrd received the Medal of Honor, which is the highest award for bravery in the United States. He was a pioneer in flying and exploring the polar regions.

Contents

Byrd's Family and Early Life

Richard Byrd was born in Winchester, Virginia. His family was one of the oldest and most important in Virginia. His ancestors included Pocahontas and John Rolfe. His brother, Harry F. Byrd, became a well-known Governor and U.S. Senator for Virginia.

Marriage and Children

In 1915, Richard married Marie Donaldson Ames. He later named a part of Antarctica, "Marie Byrd Land," after her. He also named a mountain range, the Ames Range, after her father. They had four children together. The Byrd family later moved to a large house in Boston, Massachusetts.

Friends and Supporters

Byrd was friends with Edsel Ford and his father Henry Ford, who owned the Ford Motor Company. Their support helped Byrd get money and supplies for his many expeditions to the poles.

Byrd first attended the Virginia Military Institute and the University of Virginia. He then joined the United States Naval Academy in 1908. While there, he hurt his right ankle twice. These injuries later caused him to retire from the Navy in 1916.

After graduating in 1912, Byrd became an ensign in the U.S. Navy. He served on battleships and cruisers. He even received a Silver Lifesaving Medal for saving a sailor who fell overboard twice! He also worked on the yacht of the Secretary of the Navy, where he met important people like Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Even though he had to retire due to his ankle injury in 1916, Byrd continued to serve. He helped train the Rhode Island Naval Militia.

World War I Service

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, Byrd was called back to active duty. He went to naval aviation school and became a naval aviator in 1918. He then commanded naval air forces in Nova Scotia, Canada, until the war ended. For his service, he received a commendation from the Secretary of the Navy.

After the First World War

After the war, Byrd wanted to be part of the U.S. Navy's first transatlantic crossing in 1919. He couldn't join the crew because he had served overseas. However, his skills in aerial navigation were very important. He helped plan the flight path for the mission. Only one of the three flying boats, the NC-4, successfully crossed the Atlantic.

In 1921, Byrd wanted to fly solo across the Atlantic, but the Secretary of the Navy thought it was too risky. He was then assigned to a dirigible (a type of airship) called the ZR-2. Luckily, Byrd missed his train to the airship on the day it crashed. The crash killed many of his friends and made him focus on safety for all his future trips.

Byrd also helped start the first Naval Reserve Air Station near Boston in 1923. In 1925, he joined an Arctic expedition to North Greenland. There, he met Floyd Bennett and Bernt Balchen, who would become key pilots on his most famous flights.

1926 North Pole Flight

On May 9, 1926, Byrd and pilot Floyd Bennett tried to fly over the North Pole. They used a plane called the Josephine Ford, named after the daughter of Edsel Ford, who helped pay for the trip. They flew from Spitsbergen (Svalbard) and returned to the same place, flying for almost 16 hours. Byrd and Bennett said they reached the North Pole.

When he came back to the United States, Byrd became a national hero. Congress made him a commander and gave both him and Floyd Bennett the Medal of Honor. President Calvin Coolidge presented them with their medals.

1927 Trans-Atlantic Flight

In 1927, Byrd planned to fly nonstop across the Atlantic Ocean. He wanted to win the Orteig Prize, which was for the first nonstop flight between the U.S. and France. His plane, the America, crashed during a practice takeoff, injuring Floyd Bennett. While the plane was being fixed, Charles Lindbergh made his famous solo flight and won the prize.

Even though Lindbergh won, Byrd still wanted to cross the Atlantic. With Bernt Balchen as his new chief pilot, Byrd, Balchen, and two other crew members flew the America from New York on June 29, 1927. They carried mail to show that planes could be used for commercial flights. They couldn't land in Paris because of bad weather, so they crash-landed safely near a beach in France.

In France, Byrd and his crew were treated like heroes. When they returned to the U.S., Byrd received the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Early Antarctic Expeditions

First Antarctic Expedition (1928–1930)

In 1928, Byrd started his first big trip to the Antarctic. He had two ships and three airplanes. His main ship was the City of New York. One of his planes was named the Floyd Bennett after his pilot friend who had recently passed away.

They built a base camp called "Little America" on the Ross Ice Shelf. From there, they explored using snowshoes, dog sleds, snowmobiles, and airplanes. To make the trip even more special, a 19-year-old Boy Scout named Paul Siple joined the expedition. He later became a scientist and joined all five of Byrd's Antarctic trips.

On November 28, 1929, Byrd and his team made the first flight to the South Pole and back. Byrd, pilot Bernt Balchen, radio operator Harold June, and photographer Ashley McKinley flew the Floyd Bennett. They had to drop some supplies to fly high enough over the Polar Plateau, but they made it! The flight took 18 hours and 41 minutes.

Because of this amazing achievement, Congress promoted Byrd to rear admiral. At 41 years old, he became the youngest admiral in the history of the U.S. Navy. The expedition returned home in 1930 and was honored with a gold medal. A film called With Byrd at the South Pole was also made about his journey.

Byrd was very good at getting support for his expeditions. He worked with powerful people like President Franklin Roosevelt and the Ford family. He even named places in Antarctica after them to show his thanks.

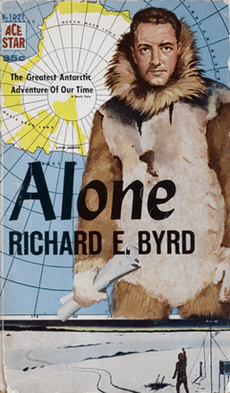

Second Antarctic Expedition (1934)

On his second trip in 1934, Byrd spent five months alone at a weather station called Advance Base. He almost died from carbon monoxide poisoning from a faulty stove. His team at the main camp noticed strange radio messages and rescued him. This dangerous experience is described in his book Alone.

A radio station was set up on his ship, the Bear of Oakland, and his adventures were broadcast to the world.

Antarctic Service Expedition (1939–1940)

Byrd's third expedition was special because it was the first one paid for by the United States government. This trip focused on studying geology, biology, and weather. They even brought a special vehicle called the Antarctic Snow Cruiser, but it broke down soon after arriving.

Byrd was called back to active duty in the Navy in March 1940, but the expedition continued without him until 1941.

World War II Service

Byrd served as a senior officer in the U.S. Navy during World War II. He was a trusted advisor to Admiral Ernest King. He traveled to the Pacific to inspect islands for airfields and even visited the fighting front in Europe.

Byrd was present when Japan surrendered in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945, which ended the war. For his service, he received the Legion of Merit twice.

Later Antarctic Expeditions

Operation Highjump (1946–1947)

In 1946, Byrd was put in charge of a huge Antarctic project called Operation Highjump. This was the largest Antarctic expedition ever, with a large naval force, many ships, helicopters, and planes. Over 4,000 people were involved.

The expedition explored a huge area of Antarctica, discovering 10 new mountain ranges. Byrd warned that in the future, countries could be attacked by planes flying over the polar regions. He said that the world was "shrinking" and that isolation was no longer a guarantee of safety.

In 1948, the U.S. Navy made a documentary about Operation Highjump called The Secret Land, which won an Academy Award.

Operation Deep Freeze I (1955–1956)

Byrd's last trip to Antarctica was for Operation Deep Freeze I in 1955–56. This mission helped set up permanent U.S. bases in Antarctica, including at the South Pole. This marked the beginning of a lasting U.S. presence on the continent.

Death and Legacy

Admiral Byrd passed away in his sleep on March 11, 1957, at his home in Boston. He was 68 years old and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Honors and Awards

By the time he died, Byrd had received 22 awards and commendations. Nine of these were for bravery, and two were for saving lives. He received the Medal of Honor, the Navy Cross, the Distinguished Flying Cross, and the Navy Distinguished Service Medal.

Byrd is the only person to have three ticker-tape parades in New York City held in his honor. He was also one of only four American military officers allowed to wear a medal with his own image on it.

He received many other important awards, including the Langley Gold Medal for aviation and the Hubbard Medal from the National Geographic Society.

In 1927, the Boy Scouts of America made Byrd an Honorary Scout. This was a new award for Americans who achieved great things in exploration and adventure. He also received the Silver Buffalo Award from the Boy Scouts in 1929.

Many places and things have been named after Richard Byrd to honor his achievements. These include:

- Richmond International Airport in Virginia.

- The Lunar crater Byrd on the Moon.

- Two U.S. Navy ships: the USNS Richard E. Byrd (T-AKE-4) and the USS Richard E. Byrd (DDG-23).

- Several schools, like Richard E. Byrd School in New Jersey and Admiral Richard E. Byrd Middle School in Virginia.

- The Byrd Polar Research Center at Ohio State University, which keeps his expedition records and personal papers.

Memorials to Byrd can also be found in New Zealand, which he used as a starting point for some of his Antarctic trips.

In 1979, the 50th anniversary of his first flight over the South Pole was celebrated with special postage stamps and a commemorative flag.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Richard Evelyn Byrd para niños

In Spanish: Richard Evelyn Byrd para niños