Richard Hooker facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Richard Hooker |

|

|

|

| Born | 25 March 1554 in Heavitree, Exeter, Devon, England |

|---|---|

| Died | 2 November 1600 (aged 46) in Bishopsbourne, Kent, England |

| Church | Church of England |

| Education | Corpus Christi College, Oxford |

| Ordained | 14 August 1579 |

| Offices held | Subdean, Rector |

| Spouse | Jean Churchman |

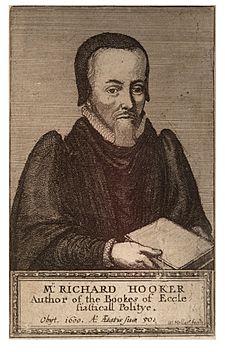

Richard Hooker (born March 25, 1554 – died November 2, 1600) was an English priest and an important thinker in the Church of England. He was one of the most influential English religious writers of the 1500s.

Hooker believed that people could use their minds and God's teachings to understand faith. His ideas helped shape the Church of England's beliefs for many years. He taught that faith should combine God's word (revelation), human reason, and old traditions.

Experts have different ideas about how Hooker fits into what we now call "Anglicanism". Some say he created a middle path (via media) between Protestantism and Catholicism. Others believe he was part of the main Protestant ideas of his time. They think he only argued against extreme groups like the Puritans. The word "Anglican" wasn't even used in his writings. It appeared later when the Church of England changed some of its views.

Contents

Early Life and Education (1554–1581)

Most of what we know about Richard Hooker's life comes from a book written by Izaak Walton. Hooker was born in a village called Heavitree in Exeter, Devon. This was around Easter in March 1554.

He went to Exeter Grammar School until 1569. Richard came from a good family, but they were not rich or noble. His uncle, John Hooker, was a successful person. He worked as the chamberlain of Exeter.

Richard's uncle helped him get support from another person from Devon, John Jewel. Jewel was the bishop of Salisbury. The bishop made sure Richard was accepted into Corpus Christi College, Oxford. Richard became a fellow there in 1577. Bishop Jewel also paid for Hooker's education.

On August 14, 1579, Hooker became a priest. He was ordained by Edwin Sandys, who was then the bishop of London. Sandys made Hooker a teacher for his son, Edwin. Richard also taught George Cranmer, who was the great-nephew of Archbishop Thomas Cranmer.

Life in London and Marriage (1581–1595)

In 1581, Hooker was asked to preach at St Paul's Cross in London. This made him a public figure. His sermon upset the Puritans because it disagreed with their ideas about predestination. The Puritans were a group who wanted to make the Church of England simpler. They wanted to remove anything they thought was too much like the Roman Catholic Church.

Hooker became involved in these debates. He also met John Churchman, a respected London merchant. According to his first biographer, Walton, Hooker made a "fatal mistake" by marrying Jean Churchman. She was the daughter of his landlady. However, some historians say Walton was not always reliable. Hooker lived with the Churchmans until 1595. It seems they treated him well and helped him a lot.

In 1584, Hooker became the rector of St. Mary's Drayton Beauchamp. But he probably never lived there. The next year, Queen Elizabeth I appointed him Master of the Temple in London. There, Hooker had public disagreements with Walter Travers. Travers was a leading Puritan and a lecturer at the Temple. Their arguments were partly about Hooker's sermon from four years earlier. But mainly, it was because Hooker said that some Roman Catholics could still be saved by God. The Archbishop stopped Travers from speaking in March 1586. The Queen's council strongly supported this decision.

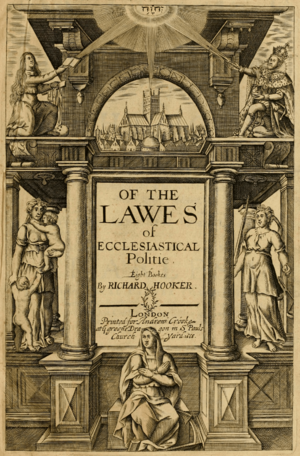

Around this time, Hooker started writing his most important work. It was called Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity. This book was a response to the Puritans. They had been criticizing the Church of England and its prayer book, the Book of Common Prayer.

In 1591, Hooker left the Temple. He was given a church position in St Andrew's, Boscombe, Wiltshire. This was to support him while he wrote his book. He mostly lived in London but also spent time in Salisbury. He was a subdean of Salisbury Cathedral and used its library. The first four parts of his major work were published in 1593.

Final Years and Legacy (1595–1600)

In 1595, Hooker became the rector of two churches in Kent. These were St. Mary the Virgin in Bishopsbourne and St. John the Baptist in Barham. He left London to continue writing. He published the fifth book of "Of the Laws" in 1597. This book was longer than the first four combined.

Richard Hooker died on November 3, 1600, at his home in Bishopsbourne. He was buried in the church there. His wife and four daughters survived him. In his will, he left money to build a new pulpit for the church in Bishopsbourne. You can still see this pulpit in the church today. There is also a statue of him there.

Major Writings

Besides his main work, Of the Lawes, Hooker wrote a few other things. These include sermons related to his arguments with Travers. He also wrote sermons connected to the later books of Of the Lawes.

Learned Discourse of Justification

This sermon from 1585 was one of the reasons Travers criticized Hooker. Travers said Hooker was teaching ideas that favored the Church of Rome. But Hooker was actually explaining their differences. He said that the Roman Catholic Church believed good deeds could make up for sins. For Hooker, good deeds were important. But they were a way to thank God for saving people, not a way to earn salvation.

Hooker believed in "Justification by faith". This means being made right with God through faith. But he also argued that even those who didn't fully understand this could still be saved by God's mercy. Hooker's way of thinking about this topic is seen as a classic example of the Anglican "middle way."

Of the Lawes of Ecclesiastical Politie

Of the Lawes of Ecclesiastical Politie is Hooker's most famous book. The first four books came out in 1594. The fifth book was published in 1597. The last three books were published after he died. Some people think he might not have written all of them himself.

This huge book was a detailed answer to the Puritans' main ideas. They believed:

- Only the Bible should guide all human actions.

- The Bible describes one unchanging way for the Church to be governed.

- The English Church was too much like the Roman Catholic Church.

- The law was wrong for not allowing lay elders (non-clergy leaders).

- There should not be bishops in the Church.

Of the Lawes is considered one of the first great works of philosophy and theology written in English. It was more than just arguing against the Puritans. It presented a complete way of thinking about faith and the Church. This thinking fit well with the Anglican Book of Common Prayer.

C. S. Lewis, a famous writer, said that Hooker added "strategy" to religious debates. Hooker's early arguments in the first two books made the Puritan position very weak. This made their later arguments seem small in comparison.

The book mainly discusses how churches should be organized and governed (their "polity"). The Puritans wanted to reduce the power of clergy and church traditions. Hooker tried to figure out the best ways to organize churches. A big part of the debate was about the role of Queen Elizabeth I. She was the Supreme Governor of the Church. If church teachings were not decided by authorities, and if everyone could interpret the Bible for themselves, then having the monarch as head of the church would be a problem. But if the monarch was chosen by God to lead the church, then local churches making their own rules would also be a problem.

In political ideas, Hooker is known for his thoughts on law and how governments started. He used many ideas from Thomas Aquinas, a famous thinker. Hooker described seven types of law. These included eternal law (God's plan), natural law (how nature works), and human law (rules made by people). Like Aristotle, Hooker believed that humans naturally want to live in groups. He said that governments are based on this natural desire to live together. They are also based on the agreement of the people being governed.

The Laws is remembered not only as a huge work of Anglican thought. It also influenced how people thought about theology, political ideas, and English writing.

Hooker's Flexible Thinking

Hooker used many ideas from Thomas Aquinas. But he changed these ideas to be more flexible. He argued that church organization, like political organization, was not something God strictly demanded. He called these "things indifferent" to God. This meant that small differences in church rules did not decide if someone was saved or not. Instead, these rules were frameworks for how believers lived their moral and religious lives.

He said there could be good monarchies or bad ones. There could be good democracies or bad ones. And there could be good church leaders or bad ones. What mattered most was how religious and good the people were. At the same time, Hooker believed that authority came from the Bible and early church traditions. But this authority had to be based on faith and reason. It wasn't just about who was in charge. This was because people should obey authority, even if it was wrong. But they should also try to fix it using good reason and the Holy Spirit. Hooker also said that the power of bishops did not always have to be absolute.

Influence and Recognition

King James I once said about Hooker's writing: "I observe there is in Mr. Hooker no affected language; but a grave, comprehensive, clear manifestation of reason, and that backed with the authority of the Scriptures, the fathers and schoolmen, and with all law both sacred and civil."

Hooker's focus on the Bible, reason, and tradition greatly influenced the development of Anglicanism. He also influenced many political thinkers, including John Locke. Locke quoted Hooker many times in his book Second Treatise of Civil Government. Locke was very influenced by Hooker's ideas about natural law and his strong belief in human reason.

Richard Hooker was known for his calm and fair way of arguing. This was unusual in the religious debates of his time. The Church of England celebrates him with a special day on November 3. Other Anglican churches also remember him on this day.

See also

In Spanish: Richard Hooker para niños

In Spanish: Richard Hooker para niños

- High church

- Low church

- Broad church

- Central churchmanship

- Anglican doctrine

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |