Robert Watson-Watt facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Robert Watson-Watt

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Robert Alexander Watson

13 April 1892 |

| Died | 5 December 1973 (aged 81) Inverness, Scotland

|

| Known for | Radar |

| Awards |

|

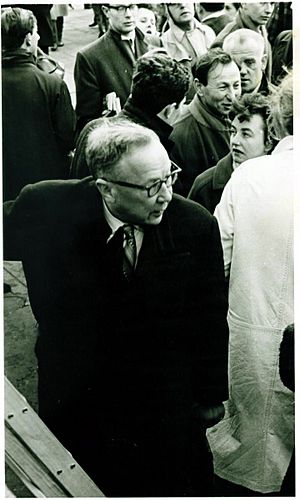

Sir Robert Alexander Watson Watt (1892–1973) was a Scottish scientist. He was a very important inventor. He helped create radar technology. Radar uses radio waves to find objects like airplanes.

Watson-Watt first worked on finding thunderstorms. He used radio signals from lightning. This led to a system called "huff-duff." It could find enemy radios very quickly. This system was vital in World War II. It helped find German U-boats (submarines).

Later, he was asked about a German "death ray." He proved it was not possible. But his assistant, Arnold Frederic Wilkins, had an idea. What if radio waves could find airplanes? This led to a test in 1935. Radio signals bounced off an airplane. Watson-Watt then led the team that built the first practical radar system. It was called Chain Home. This system helped the Royal Air Force win the Battle of Britain.

After his success, he went to the US in 1941. He advised them on air defense. He was made a knight in 1942. He also received the US Medal for Merit.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Robert Watson-Watt was born in Brechin, Angus, Scotland. His birthday was April 13, 1892. He went to school at Brechin High School. Then he studied at University College, Dundee. This college is now part of the University of Dundee.

He was a very good student. He won prizes for chemistry and physics. In 1912, he earned a degree in engineering. His professor, William Peddie, encouraged him. Peddie told him to study "wireless telegraphy," which we now call radio. Watson-Watt learned about radio waves and how they travel.

Discovering Radio Waves and Storms

In 1916, Watson-Watt joined the Met Office. This office studies weather. They wanted to use radio to find thunderstorms. Lightning creates radio signals when it strikes. Watson-Watt wanted to detect these signals. This would help warn pilots about storms.

His early tests were successful. He could find storms up to 2,500 kilometers away. He used a special antenna to point to the storm. But lightning strikes were too fast to pinpoint easily. He had to listen to many strikes to get a general location.

He first worked in Aldershot, England. In 1924, he moved to Ditton Park. Here, he used new tools. One was an Adcock antenna. It helped find the direction of a signal. The other was an oscilloscope. This device showed the signals as lines on a screen. A single lightning strike would make a line. This line showed the direction of the strike.

In 1927, Watson-Watt became director of the Radio Research Station. His team studied "static" radio signals. They found that signals could bounce off the upper atmosphere. This proved the existence of the Kennelly–Heaviside layer. This layer is high above Earth. To measure its height, they used a "time base" display. This made a dot move very fast across the oscilloscope screen. This "time base" idea was key to inventing radar.

How Radar Changed Air Defense

The Need for Better Air Defense

During First World War, German airships called Zeppelins bombed Britain. It was hard to stop them. By the 1930s, airplanes were much faster. They could bomb cities quickly. Bombers could drop bombs and leave before fighters could stop them. Britain needed a new way to defend itself.

In 1934, a committee was formed. It was led by Sir Henry Tizard. They looked for ways to improve air defense. There were rumors that Nazi Germany had a "death ray." This ray supposedly used radio waves to destroy things. In 1935, Watson-Watt was asked about it. He and his assistant, Arnold Frederic Wilkins, quickly showed it was impossible.

But Wilkins had a different idea. He noticed that airplanes could affect radio signals. What if radio waves could be used to find aircraft? Watson-Watt liked this idea. He presented it to the committee.

Finding Airplanes with Radio Waves

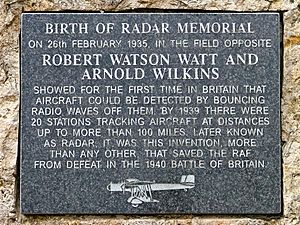

On February 12, 1935, Watson-Watt sent a secret memo. It was titled Detection and location of aircraft by radio methods. The Air Ministry wanted proof. They asked for a demonstration. Could radio waves really bounce off an airplane?

The test happened on February 26. Two antennas were set up near a BBC radio station in Daventry. The antennas were set to cancel out direct signals. Only signals from other angles would show up. A Handley Page Heyford bomber flew around the area. The receiver showed clear signals from the plane. The test was a success!

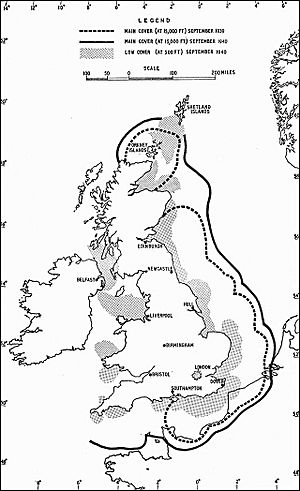

In May 1935, Wilkins and his team moved to Orford Ness. This was a quiet place on the coast. By June, they could detect planes 16 miles away. This was a huge step forward. By the end of the year, the range was 60 miles. Plans were made to build five stations around London.

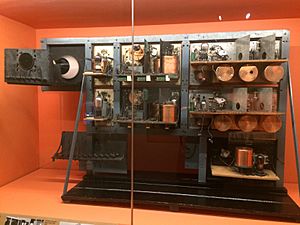

Bawdsey Manor became the main center for radar research. Watson-Watt's team used existing parts to build the radars quickly. They didn't spend time making them perfect. They wanted to get them working fast. This was his idea of the "cult of the imperfect." He believed it was better to have something good now than wait for something perfect later.

Early tests showed a problem. The radar found the planes, but telling the fighter pilots took too long. Sir Henry Tizard, Patrick Blackett, and Hugh Dowding solved this. They created a new system. It had many layers of reporting. All information went to a large room with maps. Observers would then tell the fighters what to do.

By 1937, the first three radar stations were ready. The system worked well. The government ordered 17 more stations. This became the Chain Home system. It was a line of radar towers along England's east and south coasts. By the start of World War II, 19 stations were ready. They were crucial for the Battle of Britain. The Germans knew about the towers but didn't know their purpose. They thought they were for naval communication.

Watson-Watt also worked on radar for fighter planes. This was called Airborne Interception (AI). It was perfected by 1940. This radar helped end the night bombings of 1941.

Contributions During World War II

Historians say that Watson-Watt and his team were key to winning Second World War. Their work on radar was fundamental.

In 1938, Watson-Watt became Director of Communications Development. In 1941, he went to the US. He advised them on air defense after the Pearl Harbor attack. In 1942, King George VI made him a knight. In 1946, he received the US Medal for Merit.

Ten years after being knighted, the UK government gave him £50,000. This was for his work on radar. He later moved to Canada and then the US. In 1958, he wrote a book called Three Steps to Victory.

There's a funny story about him. In the 1950s, a policeman stopped him for speeding in Canada. The officer used a radar gun! Watson-Watt reportedly said, "Had I known what you were going to do with it I would never have invented it!" He even wrote a poem about it:

Pity Sir Robert Watson-Watt,

strange target of this radar plot

And thus, with others I can mention,

the victim of his own invention.

His magical all-seeing eye

enabled cloud-bound planes to fly

but now by some ironic twist

it spots the speeding motorist

and bites, no doubt with legal wit,

the hand that once created it.

...

Honors and Legacy

- In 1945, Watson-Watt gave the Royal Institution Christmas Lectures on "Wireless."

- In 1949, a special chair for Electrical Engineering was named after him at University College, Dundee.

- In 2013, he was added to the Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame.

On September 3, 2014, a statue of Sir Robert Watson-Watt was unveiled in Brechin. The next day, a TV show called Castles in the Sky aired. It was about Watson-Watt's life.

His papers and letters are kept at the National Library of Scotland and the University of Dundee. A briefing room at RAF Boulmer is named the Watson-Watt auditorium.

Family Life

Watson-Watt married Margaret Robertson in 1916. They later divorced. In 1952, he married Jean Wilkinson in Canada. She passed away in 1964. He moved back to Scotland in the 1960s.

In 1966, at age 74, he proposed to Dame Katherine Trefusis Forbes. She was 67. She had also played a big role in the Battle of Britain. She led the Women's Auxiliary Air Force. This group provided the people who worked in the radar rooms. They lived together until she died in 1971. Watson-Watt passed away in 1973, at 81. They are buried together in Pitlochry, Scotland.

See also

In Spanish: Robert Watson-Watt para niños

In Spanish: Robert Watson-Watt para niños

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |