Ruben Salazar facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ruben Salazar

|

|

|---|---|

Salazar in 1970

|

|

| Born | March 3, 1928 Ciudad Juárez, Mexico

|

| Died | August 29, 1970 (aged 42) Los Angeles, California, U.S.

|

| Occupation | Journalist and civil rights activist |

| Years active | 1956–1970 |

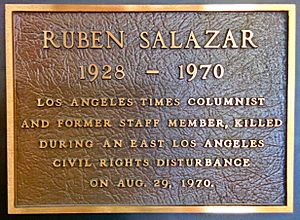

Ruben Salazar (born March 3, 1928 – died August 29, 1970) was an important journalist and a civil rights activist. He worked as a reporter for the Los Angeles Times. He was the first Mexican-American journalist from a major news company to write about the Chicano community.

Salazar died during the National Chicano Moratorium March on August 29, 1970. This march in East Los Angeles, California was a protest against the Vietnam War. During the event, a Los Angeles County Sheriff's deputy, Thomas Wilson, fired a tear-gas projectile. It hit Salazar and killed him right away. No criminal charges were filed against the deputy. However, Salazar's family later reached a financial agreement with the county.

Contents

Early Life and Moving to the U.S.

Ruben Salazar was born in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, on March 3, 1928. His family brought him to the United States in 1929. He started the process to become a U.S. citizen on October 15, 1947.

Ruben Salazar's Journalism Career

After finishing high school, Salazar served in the U.S. Army for two years. He then went to Texas Western College. He graduated in 1954 with a degree in journalism. His first job was as an investigative journalist at the El Paso Herald-Post. Once, he pretended to be homeless to get arrested. He did this to investigate how prisoners were treated in the El Paso jail. After working there, Salazar worked at several other newspapers in California.

Salazar worked as a news reporter and columnist for the Los Angeles Times from 1959 to 1970. During this time, he became a very well-known person in the Chicano movement. Early in his career at the Times, he was a foreign correspondent. This meant he reported from other countries. He covered events like the 1965 United States occupation of the Dominican Republic and the Vietnam War. He also reported on the Tlatelolco massacre while he was the Times' main reporter in Mexico City.

When Salazar came back to the U.S. in 1968, he focused on the Mexican-American community. He wrote about the Chicano movement and East Los Angeles. This area was often ignored by the media, except for crime news. He became the first Chicano journalist to cover this ethnic group for a large newspaper. Many of his articles criticized how the Los Angeles government treated Chicanos. This was especially true after he had problems with police during the East L.A. walkouts. While reporting for the Times, Salazar built connections with people in the Chicano movement.

In January 1970, Salazar left the Times. He became the news director for KMEX, a Spanish language television station in Los Angeles. At KMEX, he looked into claims that police officers were planting evidence to frame Chicanos. He also investigated a police shooting in July 1970 where two unarmed Mexican people were killed. Salazar said that undercover police detectives visited him. They warned him that his investigations were "dangerous" to people in the community.

While working at KMEX, Salazar spoke out more about Chicano issues. He made sure to cover stories that were important to the Chicano Movement. This included the killing of the Sánchez cousins by police. This event led to a large community protest. He also covered the Chicano Moratorium, which was the event where he died.

Why Ruben Salazar Supported the Chicano Movement

Ruben Salazar strongly supported the Chicano Movement. This made him stand out from other journalists in major news organizations. There were very few minority journalists across the country. Salazar felt it was his duty to bring attention to the actions led by his fellow Chicanos in East Los Angeles, California.

In February 1970, just six months before he died, Salazar clearly showed his support for the Chicano Movement. He wrote an article in the Los Angeles Times called "Who Is A Chicano? And What Is It the Chicanos Want?" In this article, Salazar described the changing identity of Chicanos. He also explained the historical importance of the movement. He shared his frustration that there were not enough Mexican-American people elected to the Los Angeles city council.

Because he supported the Chicano Movement, Salazar became a person of interest for the FBI. He had an FBI file. He was seen as cooperative when the FBI questioned him about Stokely Carmichael. However, the FBI had noticed him earlier during the Korean War. This was when he was writing to a white female pacifist about his citizenship application being lost by the army. During the Carmichael interview, Salazar said he wasn't present for the speech the FBI was asking about. He was then asked to get a video of the speech for the FBI. Salazar agreed, but only if he could tell the public that the FBI was looking for the tape. The FBI was worried this would cause public unrest, so they took back their request.

The FBI and the LAPD thought that public unrest was linked to communism. Since Salazar reported on many events where unrest happened, his files labeled him as a communist. The LAPD also had files on Salazar. This was because of an article he wrote about Police Chief Chief Davis. In the article, Salazar reported that Chief Davis had used negative words about Mexican people. Even though law enforcement was unhappy with his reporting, Salazar kept writing articles that supported the rights of the Chicano community.

Ruben Salazar's Death

On August 29, 1970, Ruben Salazar was covering the National Chicano Moratorium March. This march protested the Vietnam War. Many people believed that too many Latinos were serving and dying in the war. The march ended with a rally that was broken up by the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department using tear gas. This led to panic and disorder.

An official investigation found that Salazar's death was "at the hands of another." However, Tom Wilson, the sheriff's deputy who fired the shot, was never charged. At the time, many people thought Salazar's death was planned because he was a well-known voice in the Los Angeles Chicano community.

The disorder started when the owners of the Green Mill liquor store called the police. They complained about people stealing. Deputies arrived, and a fight began. Later that day, police trainees were brought to the area. A fight started, and the trainees were beaten. This led to more disorder. The Green Mill liquor store is still in the same place. The owners later said they did not contact the Sheriff's Department.

Salazar was resting inside the Silver Dollar Bar after the protest became violent. A witness said that "Ruben Salazar had just sat down to sip a quiet beer at the bar, away from the madness in the street." Then, a deputy fired a tear gas projectile through a curtain at the bar's entrance. It hit Salazar in the head and killed him instantly. Deputy Wilson used a 10-inch tear gas round designed to go through walls. This type of round is meant for situations where people are hiding behind barriers. It is different from a tear gas canister, which creates a large cloud of gas to break up crowds.

The story of Salazar's death was written about in "Strange Rumblings in Aztlan." This was an article by gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson for Rolling Stone magazine in 1971. On February 22, 2011, a review agency looked at the Los Angeles Sheriff's Department records about Salazar's death. After reviewing many documents, they concluded there was no proof that deputies meant to target Salazar or were watching him.

Deputy Wilson said he did not know what kind of tear gas projectile he fired. Salazar's death caught the attention of many activists in the Chicano movement. His death happened at the hands of those who the movement felt were causing problems for Chicano communities. Many Chicanos attended meetings with the district attorney about the incident. They showed their support and stood together against police actions. After several days of people giving their statements, the jury gave a mixed decision, and no charges were filed.

However, three years after Salazar's death, Los Angeles County agreed to pay Salazar's family $700,000. This was because the sheriff's department did not use "proper and lawful guidelines for the use of deadly force" during the march. At that time, this was the largest payment ever made in a settlement in Los Angeles County history.

Ruben Salazar was survived by his wife, Sally, and their daughters, Lisa Salazar Johnson and Stephanie Salazar Cook, and son, John Salazar.

Ruben Salazar's Legacy and Honors

- Salazar won the Greater Los Angeles Press Club Award two times. In 1965, he received an award from the Equal Opportunity Foundation.

- In 1971, Salazar was given a special Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award after his death.

- After his death, Laguna Park was renamed Salazar Park in his honor. This park was the site of the 1970 rally.

- Salazar is shown as "Roland Zanzibar" in Oscar Zeta Acosta's 1973 book The Revolt of the Cockroach People.

- In 1979, Sonoma State University renamed its library after Salazar. In 2002, the library moved to a new building. The old library building was then renamed Salazar Hall.

- In 1996, the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. bought a painting called Death of Rubén Salazar. It was painted by Frank Romero in 1986.

- His death was remembered in a song called a corrido by Lalo Guerrero. The song was titled "El 29 de Agosto."

- A classroom building at California State University, Los Angeles (Cal State LA) was named for him in 1976. On October 12, 2006, Salazar Hall was rededicated with a new portrait of him by John Martin.

- On October 5, 2007, the United States Postal Service announced that it would honor five journalists from the 20th century with first-class postage stamps. These stamps were issued on April 22, 2008. Ruben Salazar was one of the journalists honored.

- A documentary film about Salazar, called Ruben Salazar: Man in the Middle, was shown on PBS television on April 29, 2014.

See also

In Spanish: Rubén Salazar para niños

In Spanish: Rubén Salazar para niños

- History of Mexican Americans in Los Angeles

- List of journalists killed in the United States