Saber-toothed cats facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Saber-toothed cats |

|

|---|---|

|

|

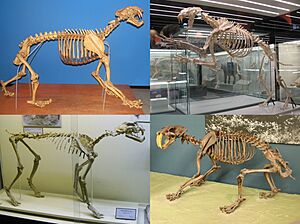

| Homotherium venezuelensis, Machairodus aphanistus, Metailurus sp. and Smilodon fatalis | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | †Machairodontinae Gill, 1872 |

| Subgroups | |

|

|

The Machairodontinae (say: Mah-kai-roh-DON-tih-nay) are an extinct group of carnivoran mammals from the cat family, Felidae. They are often called "saber-toothed cats" because of their incredibly long upper canine teeth.

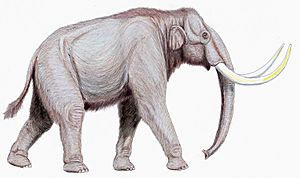

Saber-toothed cats came in many sizes. Some were as small as a lynx, while others were even bigger than a modern lion. Famous examples include Smilodon (the well-known saber-toothed tiger) and Homotherium. Not all saber-toothed animals were true cats; some other ancient predators also developed long, sharp teeth. Unlike today's big cats, which usually suffocate their prey, saber-toothed cats likely used their powerful neck muscles to drive their huge teeth into the prey's throat, causing quick blood loss.

These incredible cats first appeared in Eurasia about 20 million years ago. From there, they spread across almost every continent, except Australia and Antarctica. For a long time, saber-toothed cats were the top predators in many parts of the world. However, their numbers began to shrink over time, possibly due to changes in their environment, less prey, and competition with other large cats and even early humans. The very last saber-toothed cats, like Smilodon and Homotherium, disappeared around 12,000 to 10,000 years ago. This happened during a big extinction event that saw many large animals vanish from Earth.

Contents

The Cat Family Tree

Scientists have studied the DNA from ancient fossils. They believe that saber-toothed cats branched off from the ancestors of modern cats about 20 million years ago. The two most famous saber-toothed groups, Homotherium and Smilodon, separated from each other around 18 million years ago.

The first saber-toothed cats likely appeared in Europe during the Miocene period. An early cat called Pseudaelurus showed signs of developing longer upper canine teeth, suggesting it might be an ancestor. The oldest known saber-toothed cat is Miomachairodus, found in Africa and Turkey. For millions of years, saber-toothed cats lived alongside other ancient meat-eaters that also had long, sharp teeth.

Scientists group saber-toothed cats into different tribes based on their features. The Smilodontini tribe included "dirk-toothed" cats like Megantereon and Smilodon, which had very long, narrow teeth. The Machairodontini (also called Homotherini) tribe had "scimitar-toothed" cats like Machairodus and Homotherium, with shorter, broader teeth. Another group, the Metailurini, included cats like Dinofelis and Metailurus.

It's important to know that "saber-toothed tigers" is a bit misleading. These cats were not closely related to modern tigers. DNA studies confirm that saber-toothed cats were a very early branch of the cat family and are not direct relatives of any living cat species today.

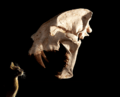

Amazing Skulls and Teeth

The skulls and teeth of saber-toothed cats are what make them so special! Scientists have learned a lot about these ancient predators by studying their unique head shapes.

Saber-toothed cats are often divided into two main types:

- Dirk-toothed cats: These had very long, narrow upper canine teeth, like daggers. They usually had strong, stocky bodies. Smilodon is a great example.

- Scimitar-toothed cats: These had shorter, broader upper canine teeth, shaped more like curved swords. They often had leaner bodies and longer legs. Homotherium is a good example.

One interesting cat, Xenosmilus, was a mix! It had the strong body of a dirk-toothed cat but the shorter, stout teeth of a scimitar-toothed cat.

To fit their huge teeth, saber-toothed cats needed to open their mouths much wider than modern cats. A domestic cat can open its mouth about 80 degrees, and a lion about 91 degrees. But Smilodon could open its mouth an amazing 128 degrees! They achieved this by having special skull shapes and smaller, more flexible jaw muscles. This meant their bite wasn't as strong as a lion's, but their neck muscles were incredibly powerful to help them use their sabers.

Bodies Built for Hunting

Dirk-toothed cats like Smilodon were built for strength. They had heavy bodies, strong shoulders, and powerful neck muscles. Their tails were quite short, like a bobcat's. Their bodies were more like modern bears than modern cats in some ways. This build suggests they were ambush hunters, not fast, long-distance runners.

Scimitar-toothed cats, like Homotherium, were more varied. Early ones were large and cat-like. Later ones, like Homotherium, were long-legged and lean, similar to a hyena. Homotherium had a sloped back, which might have helped it run long distances. It also had excellent night vision and claws that helped it grip the ground, suggesting an active hunting style.

Mummified Cub Discovery

In 2020, an incredible discovery was made in Russia: the mummified remains of a 3-week-old Homotherium latidens cub! This was the first time such a well-preserved saber-toothed cat cub had been found. Scientists were amazed by its soft, colored fur.

What They Ate and How They Bit

Saber-toothed cats were specialized meat-eaters. Their teeth were designed for slicing flesh, not for grinding plants or crushing bones like some other carnivores.

A Special Bite

Even though their teeth were huge, the jaws of saber-toothed cats were not very strong. If they just used their jaw muscles, their bite would be much weaker than a lion's. Instead, they used their incredibly strong neck muscles. When they opened their mouths very wide, their neck muscles would push their head down, driving their saber teeth into their prey. This was a powerful, precise strike.

What They Hunted

Scientists study the chemical makeup of fossilized bones to learn about ancient diets. Studies show that Smilodon mainly hunted large animals like ancient bison and horses. They also sometimes ate ground sloths and mammoths. Homotherium often hunted young mammoths and other grazers like pronghorn and bighorn sheep.

By looking at tooth wear and bite marks on bones, scientists believe saber-toothed cats were very good at stripping meat from carcasses. They could even eat smaller bones, similar to how modern lions eat.

What Did They Look Like?

Reconstructing the faces of extinct animals is tricky! Scientists debate what saber-toothed cats' ears, noses, and lips looked like. Some thought they had low ears or a pug-like nose, but there's little evidence for this.

One big question is about their lips. Some scientists think they had longer lips to cover their huge teeth and allow for a wider bite. Others believe modern cats' lips are elastic enough. Today, many artists draw saber-toothed cats with long lips, like the jowls of some large dogs. However, studies suggest that Homotherium could hide its teeth completely with its lips, while Smilodon's teeth were so long they might have always shown a little, even when its mouth was closed.

Did They Roar or Purr?

Scientists have studied the hyoid bones in the throats of Smilodon. These bones are important for making sounds. Comparisons suggest that Smilodon, and possibly other saber-toothed cats, might have been able to roar, just like modern lions! However, a recent study in 2023 suggested their hyoid bones were shaped more like "purring" cats, so the mystery continues!

Living Together: Social Behavior

Many scientists believe that some saber-toothed cats lived in groups, much like modern lions.

Smilodon Social Life

The La Brea Tar Pits in California are famous for trapping many ancient animals. Scientists noticed that many Smilodon skeletons were found there. They compared this to how modern social and solitary predators react to trapped prey. Social animals, like lions, are more likely to approach a trapped animal, while solitary ones might avoid the danger. The large number of Smilodon found suggests they were social, working together to get food.

Homotherium and Mammoth Hunting

At Friesenhahn Cave in Texas, scientists found the remains of almost 400 young mammoths alongside Homotherium skeletons. This suggests that groups of Homotherium might have specialized in hunting young mammoths. They may have dragged their kills into caves to eat safely, away from other scavengers. Their excellent night vision would have helped them hunt in the dark, especially in cold regions.

It would have been very hard for a single cat to drag a large mammoth calf into a cave. This, along with the fact that Homotherium's teeth show few breaks, suggests they worked together.

Clues from Injuries

Scientists have found many Smilodon fossils with healed injuries, like broken bones. Some of these injuries were so severe that the animal would not have been able to hunt alone. For example, one Smilodon cub had a shattered pelvis that healed, allowing it to survive into adulthood. This suggests that other members of its group must have helped it find food and protected it. Such evidence points strongly to a social lifestyle for Smilodon.

However, some scientists disagree. They point out that Smilodon had a relatively small brain, which might mean less ability for complex group behaviors. Also, solitary cats can sometimes heal from serious wounds. The debate about how social saber-toothed cats truly were continues!

How Did They Use Their Sabers?

The most debated question about saber-toothed cats is how they used their amazing teeth.

Not for Crushing Bones

One early idea was that they used their sabers to crush bones or tear open tough-skinned animals. However, teeth are fragile. Hitting hard bone would easily break their long, unsupported canines. This idea has been mostly rejected by scientists.

A Precise Throat Bite

The most widely accepted idea is that saber-toothed cats used their sabers for a very precise bite to the throat. Once they had wrestled their prey to the ground, they would use their powerful neck muscles to drive their canines into the animal's neck. The goal was to quickly cut major blood vessels, causing rapid blood loss and a fast death.

This method would be very effective and quick. It would also reduce the struggle, protecting their fragile teeth. However, it would be a very bloody kill, which might attract other predators or scavengers. This suggests that saber-toothed cats might have needed to hunt in groups to defend their kills.

The "Belly Shearing" Idea

Another interesting idea is the "belly shearing" bite. This suggests that a group of saber-toothed cats would hold down a large animal. Then, one cat would bite into the prey's belly, pulling back to create a large tear. This would cause massive blood loss and quickly kill the animal.

This method is less risky for the teeth because the belly is softer than the throat. It also creates a huge wound, leading to a quick death. However, it would require the prey to be completely still, and the cats would need to be social to work together. Some experiments with mechanical jaws on animal carcasses have shown that it might be difficult for the sabers to get a good grip on a large animal's taut belly. So, while interesting, this idea is still being explored.

Images for kids

-

A male Amphimachairodus giganteus was one of the largest machairodonts. It dwarfs its modern relative, the common house cat, Felis catus.

-

Nimravides catacopis

-

The skull of a male musk deer, displaying extreme upper canines developed only through sexual selection and otherwise completely nonfunctional.

-

La Brea Tar Pits fauna as depicted by Charles R. Knight with two Smilodon playing the role of opportunistic scavengers.

-

A modern leopard, Panthera pardus applying the conical-tooth equivalent of the "bite and compress" to a bushbuck.

-

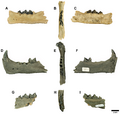

A sequence diagram of the shearing bite in the machairodont Homotherium serum: Diagram A depicts the machairodont pressing its lower canines and large incisors into the belly of the prey, creating a fold with the upward motion. Diagram B depicts the skull being depressed by the muscles of the neck, piercing the skin. Diagram C depicts the jaws clamped firmly around the section of skin and fat, and with incisors gripping the skin, the machairodont is pulling back, tearing the flap of skin from the belly.

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |