Samuel Thomas Hauser facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Samuel Thomas Hauser

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 7th Governor of Montana Territory | |

| In office July 14, 1885 – February 7, 1887 |

|

| Nominated by | Grover Cleveland |

| Preceded by | B. Platt Carpenter |

| Succeeded by | Preston Leslie |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 10, 1833 Falmouth, Kentucky |

| Died | November 10, 1914 (aged 81) Helena, Montana |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Ellen Farrar |

Samuel Thomas Hauser (born January 10, 1833 – died November 10, 1914) was an important American businessman and banker. He played a big role in developing Montana Territory. He first became rich from silver mines and railroads. But he lost his money during a tough economic time in 1893.

He then rebuilt his wealth by building dams that made electricity. However, he lost it all again when his Hauser Dam broke. Besides his many businesses, he was also the 7th Governor of the Montana Territory from 1885 to 1887. People remembered Hauser for helping Montana's economy grow with his mines, factories, railroads, and dams.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Samuel Thomas Hauser was born in Falmouth, Kentucky, on January 10, 1833. His parents were Samuel Thomas and Mary Ann Hauser. He went to the Chittenden School for his early education. Later, his father, who was a judge and lawyer, and a cousin who went to Yale University, helped with his studies.

When he was 19, Hauser started working for the Kentucky Central Railroad. In 1854, he moved to Missouri. There, he worked as a civil engineer for railroads. He began as an assistant engineer for the Missouri Pacific and Northern Pacific railways. He eventually became the chief engineer for a branch line.

Hauser married Ellen Farrar from St. Louis in 1871. They had two children together: Ellen and Samuel Thomas Jr.

Adventures in Montana

In early 1862, Hauser left his railroad job. He took a steamboat up the Missouri River. He arrived at Fort Benton, Montana, in June. From there, he traveled overland to the Salmon River. He wanted to look for gold.

The journey was hard. He heard bad news about the gold claims at Salmon River. So, he joined the gold rush at Bannack, Montana, arriving in August. The next year, he explored the Yellowstone River for gold. During this trip, his group was attacked by Native Americans. Hauser was wounded, but a thick notebook in his shirt pocket saved him. He didn't find gold on the Yellowstone. But others in his group found a lot of gold at Alder Gulch.

After the town of Virginia City quickly grew in Alder Gulch, Hauser opened a bank. In 1865, he and Nathaniel P. Langford started S. T. Hauser and Co., one of the town's first banks.

Developing Montana's Economy

Hauser himself never found much gold. Instead, he made his first fortune by investing in mines, factories (called smelters), and railroads. In 1865, he went to St. Louis to get money from investors. He succeeded, and in 1866, he started the St. Louis & Montana Mining Company. He built Montana Territory's first smelter in Argenta.

Hauser put a lot of money into silver mining. Within a few years, he owned six silver mines, coal mines, and several silver smelters. He also bought many properties to support his mining and ranching businesses.

Shipping heavy equipment and ore was very expensive. This cut into the profits of Hauser's mines. To fix this, Hauser invested heavily in railroad lines. These lines connected his mines to markets. In 1887, he worked with the Northern Pacific Railway to build the Helena, Boulder Valley, & Butte Railroad. He also built several other spur lines.

Hauser's railroads helped Montana's mining industry grow. Ores could be shipped cheaply to smelters and markets. Also, heavy equipment could be brought in. This allowed bigger and better mills and smelters to be built nearby. Hauser always promoted Montana's interests. But he also looked out for his own businesses. For example, he bought the Alta mine in 1883. It was struggling because of high transportation costs. Hauser built a railroad line to connect it to Helena. The Alta mine then became one of the richest silver mines in the territory.

Besides mining, Hauser invested in cattle. He partnered with Granville Stuart and A. J. Davis in the DHS Ranch. In 1870, Hauser joined the Washburn–Langford–Doane Expedition. He also worked to protect the Yellowstone area. His efforts helped create Yellowstone National Park. He was a member of the Democratic Party. He even attended the 1884 Democratic National Convention.

Serving as Governor

Samuel Hauser became the first person living in Montana to be appointed Governor of Montana Territory. President Grover Cleveland chose him for the job on July 3, 1885. Hauser officially started on July 14.

During his time as governor, his many business interests took up a lot of his time. He often let his personal secretary handle many of his governor duties. Some people said he only took the job to help his businesses.

As a Democrat, Hauser worked with important Republicans. This helped him further the economic growth of the territory. He also stayed connected to other western Democrats who wanted to develop the economy.

As governor, Hauser supported "free silver." This meant he wanted silver to be used as money more easily. He also supported moving Native American populations to the Indian Territory. This would free up land for new settlers. To please cattle ranchers, he appointed a territorial veterinarian. He also vetoed a plan to build a territorial mental hospital. He wanted to keep government spending low.

Hauser resigned in December 1886. He wanted to focus on his business activities. His last day in office was February 7, 1887.

Banking Challenges

In 1866, Hauser founded the First National Bank of Helena. The bank got its official permission on April 5, 1866. It had money from investors in St. Louis, and Hauser was its president. Problems started almost right away.

Risky Loans and Rules

Banks like Hauser's were regulated by the government. They had rules about how much money they had to keep in reserve. They also had rules about how much they could loan to one person. Banks had to report to government officials. These officials also hired examiners to check if banks were following the rules and staying healthy.

Under Hauser's leadership, the First National Bank of Helena often ignored these rules. Hauser said it was because Helena was so isolated. Transportation was slow, telegraph lines could be down, and communication was difficult. Because of this, banks sometimes allowed people to spend more money than they had in their accounts. This was like a short-term, interest-free loan. Ranchers and miners often did this. They would pay back the money later when they sold their animals or ore.

Hauser's bank also loaned money based only on a report of how much silver a mine had. They didn't always ask for other security. If the mine did well, the bank made money. But often, the silver would run out. Then the bank was left with nothing. The bank also accepted loans with only one signature. This was a loan based only on a person's good reputation, without much security.

Bank examiners started noticing problems. One examiner in 1870 said Hauser was often away from the bank. He also said Hauser was "more popular than competent." Another examiner, Nathaniel Langford, was Hauser's friend. He gave good reports at first. But by 1879, even Langford saw that the bank had too many risky loans. He asked Hauser to change the bank's ways.

Later examiners reported many problems. They noted poor record-keeping, too many loans, loans to the bank's own leaders, and ignoring banking laws. These issues threatened the bank's health. Hauser, however, always seemed optimistic in his public reports. He said the loans were just small technical issues.

Economic Downturn and Bank Closure

In 1893, the price of silver dropped sharply. The national economy went into a recession. Many silver mines and smelters closed, including Hauser's. Unemployment in Montana became very high. This economic downturn caused people to rush to banks to withdraw their money. Banks connected to silver, like Hauser's First National Bank of Helena, were hit hard.

On July 26, 1893, people rushed to withdraw money from Hauser's bank. This forced it to close its doors. The bank was officially suspended on July 27. In 1894, it joined with another bank, Helena National Bank, and reopened. Hauser remained its president.

However, the bank continued to have problems. In June 1896, an examiner reported that the bank was in "very weak condition." He said a small rush of withdrawals could close it. His prediction came true. The bank closed permanently that August.

After the bank closed, investigations looked into its operations. They found many issues, including poor management and risky loans. Hauser and other bank officials were criticized for how they managed the bank. The investigations found that Hauser had used the bank for his own projects and family loans. In the end, no one was punished for the problems at the First National Bank of Helena.

Building Hydroelectric Dams

After losing his first fortune, Hauser started a new project. He planned to build a series of dams on the Missouri River to create electricity. He believed that using the river's power could help Montana's mining operations grow. He named his new company the Helena Water and Electric Company.

In 1896, Hauser convinced Abram Hewitt and copper businessman William Clark to invest. Construction of the first Canyon Ferry Dam began in 1896. It was finished in 1898. The dam provided power to a factory in Corbin, Montana, a smelter in East Helena, and the city of Helena.

In 1900, Hauser formed the Missouri River Power Company. He convinced Henry Huttleston Rogers, a leader of Standard Oil, to invest. With Rogers's money, Hauser built a long power line to Butte. It was finished in 1901. In 1905, Hauser got another loan from Rogers to build a new dam.

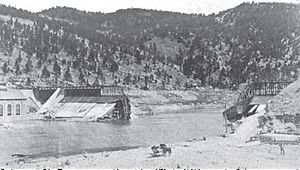

In 1906, Hauser announced plans for his new steel dam on the Missouri River. This dam, called Hauser Dam, was completed in February 1907. It was one of only three steel dams in the world. But it operated for just over a year. On April 14, 1908, it burst, sending a flood of water downriver.

Hauser was in New York when the dam broke. He sent a message saying he would rebuild Hauser Dam. He also planned to build another dam at Wolf Creek. He was very optimistic. However, many landowners below the dam claimed damages. Hauser's company had to pay a lot of money. Also, Canyon Ferry Dam couldn't make enough power to meet Hauser's agreements.

Hauser rebuilt the dam, and it started working again in the spring of 1911. But Hauser had taken on many debts he couldn't repay. Rogers, his financial supporter, had died in 1909. Meanwhile, another company built its own dam, Rainbow Dam. In September 1910, Hauser's power contracts were ended. Hauser tried to get more money from William Clark, but Clark refused. Hauser's hydroelectric business failed. Creditors took control. The dams ended up with the Montana Power Company. Hauser lost his second fortune.

Later Life and Legacy

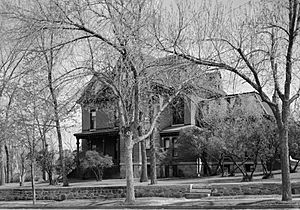

Samuel Hauser built the beautiful Hauser Mansion in Helena. It is now listed as a historic place.

Hauser died in Helena, Montana, on November 10, 1914. He was buried in the Forestvale Cemetery.

The Hauser Dam, located northeast of Helena, Montana, is named after him.