Saṃsāra facts for kids

Saṃsāra (pronounced "sam-SAH-ra") is a word from ancient Indian languages like Pali and Sanskrit. It means "wandering" or "world," but it really describes the idea of a never-ending cycle of life, death, and rebirth. This idea is a very important belief in most Indian religions, like Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism.

When connected to the idea of karma, saṃsāra is the cycle where living beings are born, live, die, and are reborn again. People also call this the "cycle of existence," "transmigration," or the "wheel of life." The goal in many of these religions is to find a way to break free from this cycle. This freedom is known by different names, such as Moksha, Nirvāṇa, or Kaivalya.

Contents

What Does Saṃsāra Mean?

The word saṃsāra means "wandering" or "cyclic change." It is a key idea in all Indian religions. It is linked to the idea of karma, which says that all living beings go through many births and rebirths in a cycle. This cycle is also called the "wheel of life" or the "karmic cycle." Many experts spell it as samsara.

The word saṃsāra comes from an older word, Saṃsṛ, which means "to go around" or "to revolve." So, saṃsāra describes a journey through different states of life. It means being reborn, growing, getting old, and dying, over and over again. This constant change is seen as the normal way of worldly life. The opposite of saṃsāra is moksha, which means freedom from this endless cycle.

The idea of saṃsāra began to develop after the ancient Vedas were written. It started to appear more clearly in early texts called the Upanishads around 800 BC. The word saṃsāra is found in several important Upanishads, often together with the idea of Moksha.

Why Do People Believe in Saṃsāra?

Saṃsāra literally means "wandering through" or "flowing on," like an aimless journey. This idea is connected to the belief that a person keeps being born again and again in different forms and places.

In very old texts, people believed that after life, you went to heaven or hell based on your good or bad actions. But ancient wise people, called Rishis, thought this was too simple. They argued that people live lives with different amounts of good and bad deeds. It would not be fair for a god like Yama to judge everyone in a simple "either/or" way.

So, they introduced the idea that you might go to heaven or hell for a time, based on your actions. But once your good or bad "points" ran out, you would return to be reborn on Earth. This idea of a cycle of life, death, rebirth, and then dying again, appears in many old and medieval texts.

How the Idea of Saṃsāra Grew

The exact beginnings of the idea of repeated rebirth, or Punarjanman, are not fully clear. However, this idea appeared in texts from both India and ancient Greece around 1000 BC.

Early Vedic texts only hinted at the idea of saṃsāra. Later Vedic texts, like the Upanishads, started to explore it more deeply. But even then, they did not explain all the details of how it worked. The full ideas of saṃsāra with their own special features began to appear around 500 BC. This happened in different traditions like Buddhism, Jainism, and various schools of Hindu philosophy.

It is hard to know who influenced whom in ancient times. It is likely that the ideas about Saṃsāra grew at the same time in different traditions, with each influencing the others.

Redeath: Dying Again

At first, people wondered if humans die only once. This led to ideas like Punarmṛtyu ("redeath") and Punaravṛtti ("return"). These early ideas suggested that human life has two parts: an unchanging inner self, called Atman, and a changing outer body in the world, called Maya. Redeath meant the end of happy times in heaven, followed by being reborn into the changing world. Saṃsāra then became a main idea about life, shared by all Indian religions.

Being reborn as a human was seen as a special chance to break free from the cycle of rebirth. This freedom is called Moksha. Each spiritual tradition in India created its own ways to reach this freedom. Some aimed for freedom in this life (Jivanmukti), while others focused on freedom after death (Videhamukti).

New ideas were added by the Sramana traditions (like Buddhism and Jainism) around the 6th century BC. They focused on human suffering. They saw rebirth, redeath, and pain as central to religious life. For the Sramanas, Saṃsāra was a cycle without a beginning. Each birth and death was just a point in this ongoing process. Spiritual freedom meant being free from rebirth and redeath.

Different Views on Saṃsāra

As saṃsāra ideas grew in different Indian traditions, they focused on different ways to find freedom. For example, in their saṃsāra ideas, Hindu traditions believed that an Ātman, or "Self," exists. They said it was the unchanging core of every living being. But Buddhist traditions said that no such soul exists, and they developed the idea of Anattā (no self).

Freedom (moksha, nirvāṇa) in Hindu traditions was described using the ideas of Ātman (self) and Brahman (universal reality). In Buddhism, freedom (nirvāṇa) was described through the idea of Anattā (no self) and Śūnyatā (emptiness).

The Ajivika tradition believed in saṃsāra but thought there was no free will. The Jainism tradition believed in a soul (called "jiva") with free will. But it stressed that strict self-control and stopping all actions were ways to break free from saṃsāra. Hindu and Buddhist traditions, however, believed in free will. They often chose giving up worldly life and living as monks to find freedom by understanding the true nature of life.

Saṃsāra in Hinduism

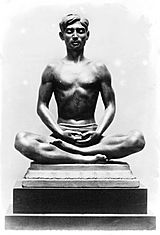

Left: Loving devotion (Bhakti) is suggested in some Hindu traditions.

Right: Meditation (Dhyāna) is suggested in other Hindu traditions.

In Hinduism, saṃsāra is seen as the journey of the Ātman, or the true Self. Hindu traditions believe that the body dies, but the Ātman does not. They see the Ātman as eternal, never-changing, and full of joy. Everything in existence is connected and follows a cycle. It is made of two things: the Self (Ātman) and the body (matter). The Ātman itself never changes or is reborn in Hinduism. However, the body and personality can change, are always changing, are born, and die.

Your current karma (actions) affect your future life, including what form you will take and where you will be reborn. Good thoughts and actions lead to a good future. Bad thoughts and actions lead to a bad future, according to the Hindu view. The journey of saṃsāra gives the Ātman chances to do good or bad actions. It also allows for spiritual efforts to reach moksha, which is freedom.

Hindus believe that living a good life and acting according to dharma (right conduct) helps create a better future. This can be in this life or in future lives. The goal of spiritual practices, whether through bhakti (devotion), karma (action), jñāna (knowledge), or raja (meditation), is to achieve self-freedom (moksha) from saṃsāra.

The Upanishads, which are part of Hindu scriptures, mainly focus on how to free oneself from saṃsāra. The Bhagavad Gita also talks about different ways to reach this freedom. The Upanishads offer a hopeful view that human nature can become perfect. The goal of human effort in these texts is a continuous journey towards self-perfection and self-knowledge to end saṃsāra. The aim is to find the true self within and to know one's Self. This state is believed to lead to a joyful state of freedom, called moksha.

Different Views within Hinduism

All Hindu traditions and philosophies share the idea of saṃsāra. However, they have different ideas about the details and what freedom from saṃsāra means. Saṃsāra is seen as the cycle of rebirth in a changing world, or Maya (illusion). Brahman is defined as that which never changes, or Sat (eternal truth). Moksha is seen as understanding Brahman and being free from saṃsāra.

Some Hindu traditions, like Madhvacharya's Dvaita Vedanta, believe in a God (like Vishnu or Krishna). They say that the individual human Self and Brahman are two different things. Loving devotion to Vishnu is the way to be free from saṃsāra. They believe that Vishnu's grace leads to moksha, and this freedom can only be achieved after death (videhamukti).

Other traditions, like Adi Shankara's Advaita Vedanta, believe that the individual Atman and Brahman are the same. They say that suffering through saṃsāra comes from not knowing this truth, from acting without thinking, and from being lazy. In reality, there are no separate parts. Meditation and self-knowledge are the ways to freedom. Realizing that one's Ātman is the same as Brahman is moksha. This spiritual freedom can be achieved in this life (jivanmukti).

Saṃsāra in Jainism

In Jainism, the ideas of saṃsāra and karma are very important. There are many writings about them in Jain texts. Jainism has had leading ideas on karma and saṃsāra since its very early days. In Jainism, saṃsāra means worldly life, which is full of continuous rebirths and suffering in different parts of existence.

The way Jainism understands saṃsāra is different from other Indian religions. For example, Jain traditions believe in a soul (called jiva), just like Hindu traditions. However, in Jainism, the cycle of rebirths, or saṃsāra, has a clear beginning and an end.

Souls start their journey in a very basic state. They exist in a continuous state of awareness that is always changing through saṃsāra. Some souls move to a higher state, while others go backward. This movement is caused by karma. Also, Jain traditions believe that some souls are Ābhāvya (incapable). These souls can never reach moksha (freedom). A soul becomes Ābhāvya after doing a very bad and intentional act. Jainism sees souls as many separate beings, each in its own karma-saṃsāra cycle. It does not believe in the idea that all souls are one, as some Hindu or Buddhist traditions do.

Jain beliefs state that each soul goes through 8,400,000 different birth situations as it cycles through saṃsāra. As the soul cycles, it goes through five types of bodies: earth bodies, water bodies, fire bodies, air bodies, and plant lives. With all human and non-human actions, like rain, farming, eating, and even breathing, tiny living beings are born or die. Their souls are believed to be constantly changing bodies. Hurting or killing any life form, including humans, is seen as a sin in Jainism. It has negative effects on one's karma.

A soul that is free in Jainism is one that has gone beyond saṃsāra. It is at the highest point, knows everything, and stays there forever. This soul is called a Siddha. A male human being is thought to be closest to this highest point and has the chance to achieve freedom, especially through strict self-control. Some Jain traditions, especially the Digambara sect, believe that women must gain good karma to be reborn as men, and only then can they achieve spiritual freedom. However, this idea has been debated within Jainism, and other sects, like the Shvetambara sect, believe that women can also achieve freedom from saṃsāra.

Jain texts clearly say that hurting or killing plants and small life forms is wrong. This is different from some Buddhist texts, which do not always say this so clearly. Jainism believes that hurting plants and small life forms creates bad karma, which negatively affects a soul's saṃsāra. However, some texts in Buddhism and Hinduism do warn people against harming all life forms, including plants and seeds.

Saṃsāra in Buddhism

Saṃsāra in Buddhism is described as a "suffering-filled cycle of life, death, and rebirth, with no beginning or end." It is also called the wheel of existence (Bhavacakra). Buddhist texts often use the term punarbhava (rebirth or re-becoming) for it. Breaking free from this cycle, known as Nirvāṇa, is the main goal of Buddhism.

Saṃsāra is seen as ongoing in Buddhism, just like in other Indian religions. Karma drives this endless saṃsāra in Buddhist thought. Unless a person reaches enlightenment, they are born and die in each rebirth. They are then reborn somewhere else based on their own karma. This endless cycle of birth, rebirth, and redeath is saṃsāra. The Four Noble Truths, which all Buddhist traditions accept, aim to end this saṃsāra-related rebirth and its cycles of suffering.

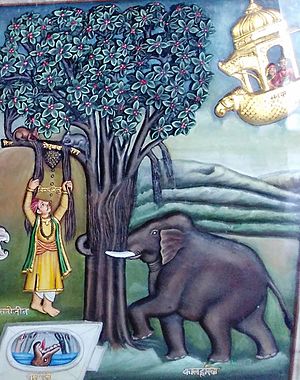

Like Jainism, Buddhism developed its own ideas about saṃsāra. Over time, it explained how the wheel of worldly existence works through endless cycles of rebirth and redeath. In early Buddhist traditions, saṃsāra had five realms where the wheel of existence recycled. These included hells (niraya), hungry ghosts (pretas), animals (tiryak), humans (manushya), and gods (devas, heavenly). Later traditions added a sixth realm: demi-gods (asuras), which were part of the gods' realm earlier. The "hungry ghost, heavenly, and hellish realms" are important parts of the rituals, stories, and moral teachings in many Buddhist traditions today.

The idea of saṃsāra in Buddhism sees these six realms as connected. Everyone cycles through life after life, and death is just a step to another life in these realms. This happens because of a mix of not knowing the truth, desires, and purposeful karma (ethical and unethical actions). Nirvāṇa is usually described as freedom from rebirth and the only way to escape the suffering of saṃsāra in Buddhism. However, Buddhist texts also developed a more detailed idea of rebirth. This idea came from fears of redeath and is called amata (death-free), a state that is seen as the same as Nirvāṇa.

Saṃsāra in Sikhism

Sikhism also includes the ideas of saṃsāra (sometimes spelled Saṅsāra), karma, and the cyclical nature of time and existence. Founded in the 15th century, its founder Guru Nanak included these cyclical ideas from ancient Indian religions. However, there are important differences between the Saṅsāra idea in Sikhism and the saṃsāra idea in many Hindu traditions. The main difference is that Sikhism strongly believes that God's grace is the way to salvation. Its teachings encourage devotion (bhakti) to One Lord for mukti (salvation).

Sikhism, like the three ancient Indian traditions, believes that the body does not last forever. It also believes there is a cycle of rebirth, and that there is suffering with each cycle. These parts of Sikhism, along with its belief in Saṅsāra and God's grace, are similar to some Hindu traditions that focus on devotion, like those found in Vaishnavism. Sikhism does not believe that living a strict, self-controlled life, as suggested in Jainism, is the way to freedom. Instead, it values being involved in society and living a family life, combined with devotion to the One God as Guru. This is seen as the path to freedom from saṅsāra.

See also

In Spanish: Samsara para niños

In Spanish: Samsara para niños

- Rebirth (Buddhism)

- Resurrection

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |