Settler colonialism in Canada facts for kids

Settler colonialism in Canada describes how people from Europe came to Canada, took control of the land, and tried to change or replace the way of life of the Indigenous peoples who already lived there. As more Europeans arrived, Indigenous peoples faced policies that forced them to give up their cultures and traditions. This is sometimes called cultural genocide.

Many government rules were made that ignored the original land rights of First Nations. The traditional ways Indigenous communities governed themselves were often replaced by systems set up by the government. Many Indigenous cultural practices were banned. First Nations people often had fewer rights and less status than the new settlers. The effects of this colonization can still be seen today in Canada's culture, history, laws, and politics.

The relationship between the Indigenous peoples in Canada and the government has been greatly shaped by settler colonialism and Indigenous resistance. In recent years, Canadian courts and governments have started to recognize and remove many unfair practices.

Contents

Government Policies and Their Impact

The "Discovery" Idea

An old idea called the Doctrine of Discovery was used to justify taking land in Canada. This idea came from Europe and said that Christian explorers could claim lands for their kings if those lands were not already ruled by Christians. This idea was used when Europeans arrived in the Americas.

Later, a Canadian court, the Supreme Court of Canada, said that this "Doctrine of Discovery" is racist. This decision questioned the right of the Canadian government to exist on Indigenous lands without their consent.

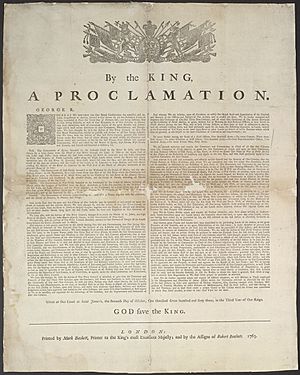

The Royal Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 is one of the most important agreements between Europeans and Indigenous peoples in Canada. King George III created this document. It recognized the rights of Indigenous peoples and set up a process for making treaties, which are still used today.

The Proclamation also said that Indigenous peoples had a right to govern themselves. Both sides agreed that treaties were the best legal way for Indigenous peoples to share control of their land. However, the British government wrote the Proclamation without asking Indigenous peoples for their ideas. This meant that only the Crown (the government) could buy Indigenous lands.

The Proclamation tried to stop white settlers from claiming land that Indigenous peoples lived on. Settlers could only get land if the Crown bought it first from Indigenous peoples and then sold it to them. But as time passed, settlers wanted to build communities and take resources like wood and minerals. They often ignored the rules of the Proclamation. Settlers saw land as something to buy and sell, not as sacred like many Indigenous peoples did. As more settlers arrived, the agreements made in the Royal Proclamation began to break down.

The Gradual Civilization Act of 1857

For a long time, Europeans wanted Indigenous people to become more like them. This goal of assimilation can be seen in the Gradual Civilization Act of 1857. This Act was based on the idea that Indigenous people were "savage" and needed to be "civilized" by Europeans.

The Act was similar to residential schools in its goal, but it focused on Indigenous men. It said that if Indigenous men wanted to join European-Canadian society, they had to give up parts of their culture. To be considered "civilized" by Europeans, a person had to speak and write in English or French and be as much like a white man as possible.

Officials checked Indigenous individuals to see if they met these rules. If they did, they could become enfranchised, meaning they gained certain rights, like the right to vote. This Act was a direct result of settler colonialism, as Indigenous people were forced to adopt the ways of the settlers.

The Indian Act of 1876

In 1876, the Canadian government passed the Indian Act. This law gave the government control over many aspects of Indigenous life, including who was considered an "Indian," reserve lands, and local Indigenous governance. The Act controlled Indigenous identity, political practices, cultural traditions, and education.

One main goal of the Act was to force Indigenous peoples to assimilate and to cause Cultural genocide. It aimed to stop Indigenous peoples from practicing their own cultural, political, and spiritual beliefs. The Act defined "Indian Status" and the rights that came with it. It also managed how land on reserves was used, how natural resources were sold, and how band councils were elected.

The Act also had rules that treated Indigenous women unfairly. For example, an Indigenous woman who married a non-Indigenous man would lose her "Indian Status." This meant she would lose her treaty benefits, health benefits, the right to live on a reserve, and even the right to be buried with her ancestors. However, if an Indigenous man married a non-Indigenous woman, he kept all his rights.

After World War II, in 1951, the Act was changed. Some bans on Indigenous culture, religion, and politics were lifted, including bans on Potlatch and Sun Dance ceremonies. These changes also allowed women to vote in band council elections. Elsie Marie Knott became the first woman elected Chief in Canada. However, these changes did not fully fix the unfairness for women regarding Status. Status was still mainly passed down through male family lines.

In 1985, the Act was changed again through Bill C-31. This change was made to match the new Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. This amendment allowed women who had lost their Status by marrying non-Indigenous men to apply to have their rights and Status restored.

Residential Schools

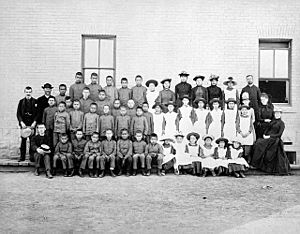

The Canadian Indian residential school system was a large network of schools set up by the Government of Canada and run by churches. These schools started in the 1880s and mostly closed by the end of the 20th century.

The main goal of residential schools was to educate Indigenous children. They taught Euro-Canadian and Christian values to make Indigenous children fit into standard Canadian culture. These values came from the colonial settlers who made up most of Canada's population at the time.

Over 150,000 Indigenous children attended residential schools in Canada. These children were often forcibly taken from their homes and families. At the schools, students were not allowed to speak their own languages or practice their cultures. If they broke these rules, they were severely punished. Residential schools were known for students experiencing physical, emotional, and psychological abuse from the staff.

The residential school system led to generations of Indigenous peoples losing their languages and cultures. Being removed from their homes at a young age also meant that many people did not learn the skills needed to raise their own families.

Settlers brought their own European ideas, believing their way of life was the best. They saw Indigenous people as "savage" and thought they needed to be "civilized" through government-ordered education. Residential schools did not truly educate Indigenous peoples. Instead, they caused a "cultural genocide" by trying to destroy Indigenous cultures. The creation of residential schools is a direct link to the values that colonial settlers brought to what is now Canada.

Ongoing Effects of Colonialism in Canada

Colonialism Today

Colonialism is when one group of people, the colonizers, takes control over another group, the colonized. Settler colonialism specifically aims to replace the original people living there. Because of colonization, Indigenous peoples in Canada have faced the destruction of their cultures and traditions through forced assimilation. Many people argue that colonialism and its effects are still happening today.

Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls

The issue of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) is an ongoing problem. It gained more attention in 2015 when the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) called for a national investigation. A 2014 report by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police showed that between 1980 and 2012, 1,017 Indigenous women were victims of homicide, and 164 Indigenous women were still missing.

Statistics show that Indigenous women aged 15 and older are three times more likely to be victims of violent crime than non-Indigenous women. Between 1997 and 2000, the homicide rates for Indigenous women were seven times higher than for non-Indigenous women.

European settlers often created unfair stereotypes about Indigenous women during the colonization of Canada. These stereotypes continue to affect Indigenous women today. The book Iskwewak--kah' ki yaw ni wahkomakanak by Canadian author Janice Accose explains how racist and sexist images of Indigenous women in books have led to violence against them, contributing to the MMIWG crisis.

A well-known example related to MMIWG is the Highway of Tears. This is a 725-kilometer stretch of Highway 16 in British Columbia. Since 1970, many murders and disappearances have happened along this highway, and a very high number of the victims have been Indigenous women.

Disproportionate Incarceration

Indigenous peoples are much more likely to be in Canadian prisons than non-Indigenous people. This is an ongoing problem in Canada's legal system. This high rate of incarceration comes from many issues caused by settler colonialism that Indigenous peoples face daily. These issues include poverty, less access to education, and fewer job opportunities.

In 1999, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled in R v Gladue that courts must consider the "circumstances of Aboriginal offenders." This led to the creation of Gladue reports. These reports help courts understand how colonialism has harmed an Indigenous person being sentenced. They consider things like cultural oppression, abuse suffered in residential schools, and poverty.

Thirteen years after the Gladue decision, the Supreme Court of Canada repeated this rule in R v Ipeelee. This decision required courts to consider the impact of colonialism on every Indigenous person being sentenced. These decisions were made to reduce the number of Indigenous peoples in prison. However, this number has continued to grow.

Indigenous peoples make up about 5% of Canada's total population. Yet, in 2020, Indigenous people made up over 30% of those in prison. Also, in 2020, Indigenous women accounted for 42% of all female inmates in Canada. Compared to non-Indigenous people, Indigenous peoples are less likely to be released early on parole. They are also more often placed in maximum security prisons and are more likely to be involved in incidents where force is used or where they injure themselves. They are also more often placed in isolation.

Indigenous Resistance

Walking with Our Sisters

Walking with Our Sisters is an ongoing movement related to MMIWG. It is a special art display that uses "vamps," which are the tops of Moccasins. Each vamp represents the unfinished life of an Indigenous woman who is missing or has been murdered.

Another art display called Every One by Cannupa Hanska Luger shows the strength of Indigenous communities. This large art piece, made from ceramic beads, was shown at the Gardiner Museum in Toronto. The beads form the face of an Indigenous woman, and each bead represents a Missing or Murdered Indigenous person. Indigenous people helped make these beads to raise awareness about this serious situation. The art piece aims to remind people that these are real individuals, not just statistics. It also challenges the old settler idea that Indigenous peoples were "savages." This artwork stands against the dehumanization of Indigenous individuals and forces viewers to face the reality of the MMIWG crisis.

Wet'suwet'en Resistance to Pipeline Projects

The Wetʼsuwetʼen First Nation, located in British Columbia, has been fighting for a long time against the Canadian government to protect their rights and land. They won an important legal case in 1997 called Delgamuukw v British Columbia. This case built on an earlier one, Calder v British Columbia, and helped confirm that Aboriginal title (Indigenous land rights) existed before Canada became a country and could exist outside of Canadian control. It also said that the Canadian government could not unfairly infringe on these rights.

While some Indigenous groups made treaties with the Canadian government, the Wet'suwet'en restated their right to govern themselves. In 2008, they completely left the treaty process with British Columbia.

See also

- Acculturation

- Cultural assimilation of Native Americans

- European colonization of the Americas

- Indigenous peoples in Canada

- Language shift

- Indigenous Peoples and the Canadian Criminal Justice System