Shrewsbury Abbey facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Shrewsbury Abbey |

|

|---|---|

| Abbey Church of the Holy Cross, Shrewsbury | |

| Church of the Abbey of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, Shrewsbury | |

|

|

| 52°42′27″N 2°44′39″W / 52.70750°N 2.74417°W | |

| Location | Shrewsbury, Shropshire |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Churchmanship | Liberal Anglo-Catholic with choral tradition |

| History | |

| Status | Active |

| Founded | 1083 |

| Dedication | Holy Cross |

| Relics held | St Winifred |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Parish church |

| Heritage designation | Scheduled monument, Grade I listed building |

| Style | Romanesque, Gothic |

| Groundbreaking | 11th century |

| Completed | 14th century |

| Specifications | |

| Number of towers | 1 |

| Materials | Red sandstone |

| Administration | |

| Parish | Holy Cross, Shrewsbury |

| Diocese | Lichfield |

| Province | Canterbury |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Full name | The Abbey of Saint Peter and Saint Paul |

| Order | Benedictine |

| Denomination | Catholic Church |

| Established | 1083 |

| Disestablished | 1540 |

| Dedicated to | St Peter & St Paul |

| Architecture | |

| Status | Dissolved |

| Heritage designation | Scheduled monument |

| Style | Romanesque, Gothic |

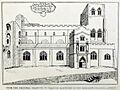

The Abbey Church of the Holy Cross, usually called Shrewsbury Abbey, is a very old church in Shrewsbury, the main town of Shropshire, England.

The Abbey was started in 1083 by a Norman nobleman named Roger de Montgomery. He built it as a monastery for Benedictine monks. It became one of the most important abbeys in England and a popular place for people to visit on religious journeys called pilgrimages.

A lot of the abbey was destroyed in the 1500s. But the main part of the church, called the nave, was saved. Today, it is the main church for the Parish of Holy Cross. The abbey is a special historic site, protected as a Grade I listed building. It is located just east of Shrewsbury's town centre.

Contents

History of the Abbey

How the Abbey Began

Before the Normans came to England, a small wooden church stood on this spot. It was built by a Saxon landowner named Siward.

In 1071, William the Conqueror gave Shropshire to his loyal earl, Roger de Montgomery. Earl Roger was persuaded by his clerk, Odelerius, to build a monastery. On February 25, 1083, Earl Roger promised to build the abbey. He gave the land and brought two monks from Normandy, France, to start the community.

The new abbey was built around the old Saxon church. When it was ready in 1087, monks began their regular life there under their first leader, Abbot Fulchred. Earl Roger gave the abbey many gifts of land and property to support the monks.

A Difficult Start

The abbey's early years were not easy. After Earl Roger's son, Robert of Bellême, rebelled against King Henry I in 1102, the king took away his lands. This meant the abbey lost its powerful local protector. Some people who had promised to give land to the abbey tried to back out of their promises.

However, King Henry I supported the abbey. Around 1121, he gave the monks special rights. One of the most valuable gifts was the right to all the grain milling in Shrewsbury. This meant everyone had to pay the monks to grind their corn into flour, which gave the abbey a steady income.

The Famous Relics of St. Winifred

In 1137, a monk named Robert of Shrewsbury had a brilliant idea. He decided to bring the bones of a Welsh saint, St. Winifred, to the abbey. At the time, St. Winifred was not very well known.

Robert and other monks traveled to Gwytherin in Wales. They carefully dug up the saint's remains and carried them back to Shrewsbury. The journey took a week on foot. When the relics arrived, they were placed in the abbey church. People claimed that miracles happened, and soon, the abbey became a famous centre for pilgrimage. Thousands of people came to visit the shrine of St. Winifred, making the abbey wealthy and important.

Life as a Monk

Life for the monks at Shrewsbury was not as strict as in some other monasteries. They lived in a busy town and were involved in the local community. The abbey owned properties in the town, including orchards and a vineyard.

The monks managed their lands well. They hired local people to farm the land for them. Inside the abbey, discipline was generally good. The monks followed their daily schedule of prayer and work. By the 1300s, the abbey was even sending one or two monks to university to study theology.

Powerful Abbots

The leader of the abbey was called an abbot. Over time, the abbots of Shrewsbury became very powerful. Because the king was the abbey's official protector, the abbot was considered a major landowner. He even had to attend Parliament in London.

The abbots were important political figures. One abbot, Thomas Prestbury, was even the Chancellor of Oxford University in the early 1400s. This brought great honour to the abbey.

Later Middle Ages

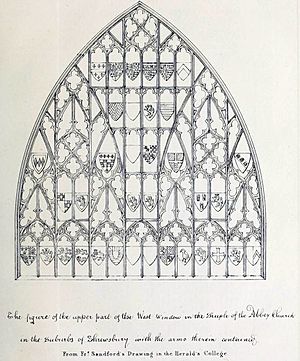

The 1300s and 1400s were a time of change. The Black Death, a terrible plague, caused many problems. But the abbey survived and even carried out major rebuilding work. The beautiful great west window was probably added during this time.

The abbey's monks were very protective of their relics. They even stole the relics of St Beuno, St. Winifred's uncle, from a church in Wales. They were fined but were allowed to keep the bones. A new, grander shrine was also built for St. Winifred.

The End of the Abbey

Decline and Dissolution

In the early 1500s, during the reign of King Henry VIII, the abbey began to have problems. The king decided to break away from the Catholic Church in Rome. This event is known as the English Reformation.

Henry VIII needed money, and the monasteries were very wealthy. In 1536, he began to close them down in an event called the Dissolution of the Monasteries. At first, only the smaller monasteries were closed. But soon, the king's officials came for the larger ones too.

Shrewsbury Abbey was one of the last major abbeys to be closed. It was officially surrendered to the king on January 24, 1540. The abbot and the 17 monks were given pensions, and the abbey's buildings and lands were taken by the Crown.

After the Dissolution

After the abbey was closed, most of its buildings were torn down for their stone and lead. The abbot's house and the infirmary were left to fall into ruin. The land was sold to private owners.

However, the main part of the abbey church—the nave—was saved. It had always been used as the local parish church for the area called Abbey Foregate. It continued to serve this purpose and is still an active church today.

In the 1800s, the engineer Thomas Telford built a new main road right through the old abbey grounds. This destroyed much of what was left of the original monastery layout. Today, only a few original parts remain outside the main church, including a stone pulpit where a monk would have read to others during meals.

The Church Today

The church you see today is a mix of old and new. Much of the original Norman building from the 11th century is still there, especially the massive round pillars inside.

During the 1800s, the church was carefully restored. A new roof was built, and the east end of the church was redesigned by the famous architect John Loughborough Pearson.

Inside, you can find war memorials for local people who died in the World Wars. One of the names on the First World War memorial is the famous war poet Wilfred Owen. There is also a modern sculpture in the churchyard dedicated to him.

Music at the Abbey

The Abbey has a long history of beautiful church music. Today, it has an excellent adult choir that sings at most services.

The church also has a magnificent pipe organ, built in 1911 by the famous organ builders William Hill and Son. It was designed to be as grand as an organ in a cathedral. After many years of fundraising, the organ was fully restored and completed in 2021. It is now known for its glorious sound that fills the large abbey space.

Brother Cadfael

Shrewsbury Abbey is famous as the setting for the historical mystery novels The Cadfael Chronicles by Ellis Peters. The main character is Brother Cadfael, a fictional monk who lives at the abbey in the 1140s.

Cadfael is a clever monk who uses his knowledge of herbs and human nature to solve crimes. The stories are set during a real historical period called The Anarchy, a civil war between King Stephen and Empress Maud. The popular books and TV series have made Shrewsbury Abbey famous to people all over the world.

Burials

Several important historical figures were buried at the abbey, including:

- Roger de Montgomerie, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury, the founder of the abbey.

- Hugh of Montgomery, 2nd Earl of Shrewsbury, his son.

- William FitzAlan, Lord of Oswestry, a powerful local lord.

Images for kids

See also

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |