Sir Charles Asgill, 2nd Baronet facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sir Charles Asgill, Bt

|

|

|---|---|

colourised image of Asgill from a mezzotint of lost original by Thomas Phillips

|

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | 6 April 1762 London, England |

| Died | 23 July 1823 (aged 61) London, England |

| Political party | Whig |

| Spouse | Jemima Sophia Ogle |

| Relations | Sir Charles Asgill, 1st Baronet and Sarah Theresa Pratviel. |

| Residences | 29 Old Burlington Street, London (1778-1785). 6 York Street, St. James's (1791–1821) |

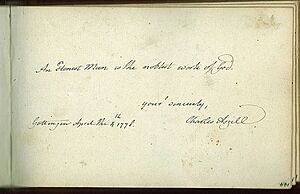

| Alma mater | Westminster School University of Göttingen |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1778–1823 |

| Rank | General |

| Battles/wars | American War of Independence (1775–1783) Flanders campaign (1792–1795) Irish Rebellion of 1798 Irish Rebellion of 1803 |

General Sir Charles Asgill, 2nd Baronet (born April 6, 1762 – died July 23, 1823) was a dedicated soldier in the British Army. He is best known for the "Asgill Affair" in 1782. During the American Revolutionary War, he was sentenced to death as a prisoner of war. However, the American forces who held him changed their minds. This happened because the government of France stepped in to help him. Later in his career, he fought in the Flanders campaign. He also helped stop the Irish Rebellion of 1798 and was a commander during the Irish rebellion of 1803.

Contents

Early Life and Military Start

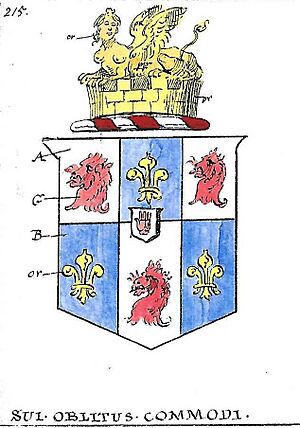

Charles Asgill was born on April 6, 1762, in London. He was the only son in a family with good connections. His father, Sir Charles Asgill, 1st Baronet, was a banker and had been the Lord Mayor of London. His mother, Sarah Theresa Pratviel, came from a French Huguenot family. Her father was a secretary to the ambassador in Spain. The family lived at Richmond Place, which is now called Asgill House.

Charles went to Westminster School and the University of Göttingen. Even though his father wanted him to stay in England, Charles joined the army. He became an ensign in the 1st Foot Guards on February 27, 1778, just before his 16th birthday. This regiment is now known as the Grenadier Guards. By February 1781, Asgill was promoted to lieutenant and then captain.

The Asgill Affair: A Prisoner's Story

Becoming a Prisoner of War

In early 1781, Asgill was sent to North America to fight in the American Revolutionary War. He served under General Cornwallis. Asgill fought in the Siege of Yorktown. After Cornwallis's army surrendered in October 1781, Asgill became an American prisoner of war.

Even after the surrender at Yorktown, fighting continued between American patriots and British loyalists. A loyalist named Philip White was killed by patriots. In return, loyalists captured an American captain named Joshua Huddy. He was taken to a prison in New York. A British officer, Richard Lippincott, took Huddy from British custody and had him executed. This was ordered by William Franklin.

American soldiers protested this. To stop more violence, George Washington ordered that a British officer be chosen by chance to be executed in return. This was meant to be a warning.

The Unfortunate Selection

On May 27, 1782, Washington's orders were carried out. Thirteen British officers were gathered at a tavern. They refused to choose one of their own for execution. So, a drummer boy drew lots (pieces of paper). Asgill's name was picked, along with the word "unfortunate." This meant he was chosen for execution.

Some people, like Alexander Hamilton, thought Washington's order was wrong. Washington himself later realized it might have been a mistake. He asked why other types of prisoners were not chosen instead.

Imprisonment and International Attention

Asgill was moved from Lancaster to Chatham. At first, he was treated well by Colonel Elias Dayton. But then he was sent to Timothy Day's Tavern. Here, he faced harsh conditions. He was beaten, given bad food, and people paid to watch him suffer. He also heard false news that his father had died.

The British military put Lippincott on trial for Huddy's execution. But Lippincott was found not guilty because he was following orders. Washington wanted Lippincott to be given to the Americans in exchange for Asgill, but this was refused.

Asgill's situation became very famous around the world. The government of France even got involved to help him. Washington felt a lot of pressure. He decided that the decision about Asgill's fate was too big for one person. So, he sent the matter to the Continental Congress to decide.

Release and Aftermath

When Asgill's mother, Lady Sarah Theresa Asgill, heard about her son, she asked for help from British ministers and King George III. She also wrote a letter to the comte de Vergennes, who was the French Foreign Minister. Vergennes showed her letter to King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette. They ordered Vergennes to write to Washington. The letter said that executing Asgill would go against a treaty signed by France, America, and Britain.

Lady Asgill sent a copy of Vergennes' letter to Washington herself. This copy reached Washington before the original from Paris. On October 30, Washington sent the letters to the Continental Congress. The Congress was about to vote to hang Asgill. After several days of discussion, on November 7, Congress voted to release Asgill. This was done "as a compliment to the King of France."

A week later, Washington sent Asgill a letter with a passport to go home. Asgill left Chatham immediately on November 17, 1782.

Years later, Washington heard that Asgill was spreading rumors about being treated badly as a prisoner. Washington was upset, saying Asgill had been treated well. He published his letters about the case. Asgill then wrote his own letter in 1786, denying the rumors and describing his mistreatment. This letter was not published until 2019.

Later Military Career

In 1788, Asgill became an equerry (an officer who attends a royal person) to Frederick, Duke of York. He kept this job until he died. On September 15, 1788, he became the 2nd Baronet after his father passed away. In 1790, he was promoted to lead a company in the 1st Foot Guards, with the rank of lieutenant-colonel.

He fought in the Flanders campaign in 1793 under the Duke of York. Two years later, he became a colonel.

Role in the Irish Rebellion of 1798

In June 1797, Asgill was made a brigadier-general in Ireland. He became a major-general on January 1, 1798. He was very active against the rebels during the Irish Rebellion of 1798. He received thanks from his commanders and the government for his actions.

General Sir Charles Asgill marched from Kilkenny and fought against the rebels, making them scatter. The city of Kilkenny gave him a special snuff box for his "energy and exertion."

In 1800, Asgill was transferred to lead the 2nd Battalion of the 46th (South Devonshire) Regiment of Foot. He later went to Ireland again in 1802. He commanded the army in Dublin and the training camps at the Curragh.

Service in Dublin and Promotions

In 1801, Asgill helped a man named Henry Ellis. Ellis had provided important information during the rebellion. This information helped stop the rebels. But after the fighting, Ellis's neighbors caused him trouble and ruined his business. Asgill helped him get paid properly by the British government.

Asgill stated that on March 18, 1803, he was put in charge of the Eastern District of Ireland. This included the army in Dublin. He was in command during the rebellion that started in Dublin in July 1803.

Asgill was promoted to lieutenant general in January 1805. He also became the leader of several different regiments, including the 11th (North Devonshire) Regiment. He even paid out of his own pocket to equip a second battalion for the 11th Regiment. He had trouble getting his money back from the government.

Retirement and Final Years

In 1812, Asgill was told he would no longer be on the army staff in Ireland. He was almost 50 years old. He wrote that he would return to England with less money and no job. This was hard for him after 34 years of continuous service.

Asgill continued to serve until 1812. On June 4, 1814, he was promoted to general. In 1820, he received a high honor called the Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Guelphic Order.

Personal Life and Death

On August 28, 1790, Asgill married Jemima Sophia (1770-1819). She was the sixth daughter of Admiral Sir Chaloner Ogle, 1st Baronet. From 1791 to 1821, Asgill lived at No. 6 York Street in London. The Asgills were friends with important people like the Duchess of Devonshire. They also enjoyed going to the theater with their friend Richard Brinsley Sheridan. Lady Asgill died in 1819.

Sir Charles Asgill died in 1823. When he died, the Asgill baronetcy (his title) ended because he did not have any children.

Images for kids

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |