South Island takahē facts for kids

Quick facts for kids South Island takahē |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| On Tiritiri Matangi Island | |

| Conservation status | |

Nationally Vulnerable (NZ TCS) |

|

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Gruiformes |

| Family: | Rallidae |

| Genus: | Porphyrio |

| Species: |

P. hochstetteri

|

| Binomial name | |

| Porphyrio hochstetteri (A. B. Meyer, 1883)

|

|

|

|

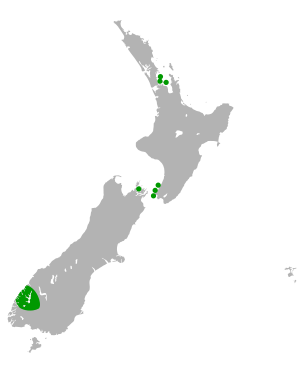

| Distribution of South Island takahe, including sanctuaries | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The takahē (Porphyrio hochstetteri), also called the South Island takahē, is a flightless bird that lives only in New Zealand. It is the biggest living member of the rail family, which includes birds like pukeko.

People in Europe first learned about the takahē in 1847. Only four birds were found in the 1800s. After the last one was caught in 1898, and no more could be found, people thought the takahē was extinct, meaning it had died out completely.

But 50 years later, in 1948, a careful search led by Geoffrey Orbell found takahē again! They were discovered in a hidden valley in the South Island's Murchison Mountains.

Today, the Department of Conservation in New Zealand looks after the takahē. Their Takahē Recovery Programme helps these birds. They live on several islands and in Takahē Valley. The bird has also been brought back to Kahurangi National Park.

Even though takahē are still a threatened species, their status improved in 2016. The population is growing, with 418 birds counted in October 2019. This number increases by 10 percent each year.

Contents

How Takahē Were Discovered

In 1847, fossil bird bones were found in South Taranaki on the North Island. These bones were sent to an expert named Richard Owen. In 1848, he named the new bird Notornis, which means "southern bird." He called the species Notornis mantelli. Scientists thought this bird was another extinct species, like the moa.

Two years later, in 1849, some sealers in Dusky Bay, Fiordland, saw a large bird. They chased it with their dogs. The bird ran very fast and screamed loudly when caught. The sealers kept it alive for a few days, then cooked and ate it, saying it was delicious.

Luckily, Walter Mantell met the sealers and got the bird's skin from them. He sent it to his father, Gideon Mantell. Gideon realized this was Notornis, a bird thought to be extinct! In 1850, he showed the skin to the Zoological Society of London.

Another takahē was caught by Māori people on Secretary Island, Fiordland, in 1851. Māori people already knew about takahē and traveled far to hunt them. The bird's name comes from the Māori word takahi, which means "to stamp or trample."

Only two more takahē were found by Europeans in the 1800s. One was caught by a rabbit hunter's dog near Lake Te Anau in 1879. It was bought by a museum in Dresden, Germany, but was destroyed during World War II.

Another takahē was caught by a dog named 'Rough' near Lake Te Anau on August 7, 1898. The dog's owner, Jack Ross, tried to save the bird, but it died. He gave it to William Benham at Otago Museum. This bird was in great condition. The New Zealand government bought it for a lot of money and put it on display. For many years, it was the only takahē on display anywhere in the world.

After 1898, people still reported seeing large blue-and-green birds. They called them "giant pukakis." But none of these sightings were confirmed. Only fossil bones were found. The takahē was then believed to be extinct.

How Scientists Classify Takahē

The third takahē ever collected by Europeans went to a museum in Dresden. The museum's director, Adolf Bernhard Meyer, studied its skeleton. He noticed that the bones of the Fiordland bird were different enough from the North Island specimen to be a separate species. He named it Notornis hochstetteri, after the geologist Ferdinand von Hochstetter.

Later, scientists decided that the North and South Island takahē were actually subspecies of the same bird. They were then grouped with the closely related Australasian swamphen or pukeko (Porphyrio porphyrio).

However, recent studies of living and extinct Porphyrio birds showed that the North and South Island takahē are indeed separate species, just as Meyer first thought. The North Island takahē (P. mantelli) was known to Māori as mōho. It is now extinct and only known from bones. Mōho were taller and thinner than takahē.

The takahē living in the South Island came from a different group of Porphyrio porphyrio birds. They likely arrived in New Zealand much earlier and then evolved to become large and flightless.

Rediscovery of Living Takahē

Living takahē were dramatically rediscovered by an expedition led by Invercargill doctor Geoffrey Orbell. This happened near Lake Te Anau in the Murchison Mountains on November 20, 1948. The search began when unknown bird footprints were found near the lake. Two takahē were caught, but they were released back into the wild after photos were taken.

What Takahē Look Like

The takahē is the largest living bird in the Rallidae family. It is about 63 centimeters (25 inches) long. Males weigh about 2.7 kilograms (6 pounds), and females weigh about 2.3 kilograms (5 pounds). They can weigh anywhere from 1.8 to 4.2 kilograms (4 to 9 pounds). They stand around 50 centimeters (20 inches) tall.

Takahē are strong, stocky birds with short, powerful legs. They have a very large beak that can give a painful bite. Even though they cannot fly, they sometimes use their small wings to help them climb up hills.

Adult takahē have beautiful, shiny feathers that are mostly dark blue or navy blue on their head, neck, and belly. Their wings are peacock blue, and their back and inner wings are teal and green. The tail is olive-green on top and white underneath.

Takahē have a bright red shield on their forehead and red beaks with shades of red. Their red legs were described as "crayfish-red" by those who rediscovered them.

Males and females look similar, but females are a bit smaller. Chicks are born with fluffy, jet-black down and have very large brown legs. Their beaks are dark with a white tip. Young takahē have duller colors than adults, and their dark beaks turn red as they grow up.

Takahē are noisy birds. They make a warning call that sounds like "womph." They also have a loud "clowp" call. Their contact call can sound like a weka (Gallirallus australis), but it is usually deeper.

Takahē Behavior and Habitat

Takahē are birds that stay in one place and cannot fly. They live in alpine grasslands, which are high-up grassy areas. They are very territorial, meaning they protect their space. When snow arrives, they move down to forests or bushy areas.

Takahē eat grass, plant shoots, and insects. But they mostly eat the leaves of Chionochloa tussock grass and other mountain grasses. You can often see a takahē pulling up a snow grass stalk. It holds the stalk with one claw and eats only the soft lower parts, which seem to be its favorite food. The rest of the stalk is thrown away.

One takahē was seen eating a paradise duckling at Zealandia. While this was new behavior for takahē, their relatives, the pukeko, sometimes eat the eggs and chicks of other birds.

Takahē Reproduction and Life Cycle

Takahē are monogamous, meaning a pair stays together for a long time, possibly their whole lives. They build a large nest under bushes and lay one to three buff-colored eggs. The number of chicks that survive can be anywhere from 25% to 80%, depending on where they live.

Where Takahē Live Now

Takahē originally lived in swamps. But humans turned these swampy areas into farms, forcing the takahē to move up into the grasslands. The birds are still found in the Murchison Mountains where they were rediscovered.

Small groups of takahē have also been moved to five islands where there are no predators. These islands are Tiritiri Matangi, Kapiti, Maud, Mana, and Motutapu. Visitors can see them there.

You can also see takahē in special wildlife centers like Te Anau and Pukaha / Mount Bruce National. In 2006, a pair of takahē were moved to the Maungatautari Restoration Project. In 2010, two takahē were released at Willowbank Wildlife Reserve, which was the first time a non-government place held this species. In 2011, two takahē were released in Zealandia, Wellington. In 2015, two more were released on Rotoroa Island in the Hauraki Gulf. Takahē have also been moved to the Tawharanui Peninsula. In 2014, two pairs were released into a private fenced area called Wairakei golf and sanctuary, where their first chick was born in 2015.

In October 2017, there were 347 takahē, an increase of 41 from the year before. The Orokonui Ecosanctuary has one breeding pair, Quammen and Paku. They had two chicks in 2018, but both died from heavy rains.

In 2018, eighteen takahē were brought back to Kahurangi National Park. This was 100 years after they had disappeared from that area.

Protecting the Takahē

The takahē almost disappeared for several reasons. Too much hunting, losing their homes, and new animals brought by humans (like stoats and deer) all played a part. Red deer eat the same plants as takahē, so they compete for food. Stoats hunt takahē. Also, as forests grew after the ice age, the takahē's grassland homes shrank.

Since takahē live a long time, reproduce slowly, and take years to grow up, they have problems with inbreeding. This means there isn't enough variety in their genes, which makes it harder for them to survive. Scientists use genetic tests to choose which birds to breed in captivity to keep their genes as varied as possible.

Why Takahē Numbers Declined

Scientists believe that climate changes were the main reason takahē numbers dropped before Europeans arrived. The changing temperatures were not good for these birds. Takahē live in alpine grasslands, but the end of the ice age destroyed many of these areas, causing their numbers to fall sharply.

Then, about 800–1,000 years ago, Polynesian settlers arrived. They brought dogs and Polynesian rats and hunted takahē for food, which caused another decline. When Europeans settled in the 1800s, they almost wiped out the takahē. They hunted them and brought more animals like deer, which competed for food, and predators like stoats, which hunted the birds directly.

Takahē Population and Conservation Efforts

After facing extinction, takahē are now protected in Fiordland National Park. However, the population there has not fully recovered since 1948. In fact, the takahē population dropped from 400 to 118 in 1982 because of competition with deer. To help, the national park now uses helicopters to hunt deer.

The rediscovery of the takahē created a lot of public interest. The New Zealand government quickly closed off a remote part of Fiordland National Park to protect the birds. At first, some groups thought the takahē should be left alone. But many worried they would go extinct like the huia, another native New Zealand bird. So, people started to suggest moving takahē to "island sanctuaries" and breeding them in captivity. For almost ten years, nothing was done due to a lack of resources.

Biologists from the Department of Conservation used their knowledge of island sanctuaries to create safe homes for takahē. They moved birds to Maud Island, Mana Island, Kapiti Island, and Tiritiri Matangi Island. These moves have been successful. However, the island populations might be reaching their limit, which could slow growth and increase inbreeding over time.

Recently, people have had to help takahē breed successfully. This is because their breeding rate in the wild is low. Methods like removing eggs that cannot hatch and raising chicks in captivity have been used. In Fiordland, these methods have helped a lot.

Sadly, several takahē have been accidentally killed by deer hunters working for the Department of Conservation. These hunters were trying to control populations of the similar-looking pukeko. One bird was killed in 2009, and four more (5% of the total population) were killed in 2015.

Future Plans for Protection

The original plans to help takahē, made in the early 1980s, are now well underway.

Moving takahē to islands without predators began in 1984. On these islands, the birds also get extra food. Takahē now live on five small islands: Maud Island, Mana Island, Kapiti Island, Tiritiri Matangi Island, and Motutapu Island.

The Department of Conservation also runs a breeding program at the Burwood Breeding Centre near Te Anau. This center has five breeding pairs. Chicks are raised with very little human contact. The young birds from this center are used to start new island populations and add to the wild population in the Murchison Mountains. The Department of Conservation also manages wild takahē nests to help more chicks survive. Extra eggs from wild nests are taken to the Burwood Breeding Centre.

An important step has been to strictly control deer in the Murchison Mountains and other takahē areas. After deer hunting by helicopter started, deer numbers dropped a lot. The plants that takahē eat are now growing back. This better habitat has helped takahē breed more successfully and survive longer. Scientists are also studying how much stoats affect takahē to decide if more action is needed to control them.

Takahē Population Numbers

One of the main goals was to have a self-sustaining population of over 500 takahē. At the start of 2013, there were 263 takahē. In 2016, the population grew to 306. In 2017, it reached 347, which was a 13 percent increase from the year before. In 2019, the population increased to 418.

Images for kids

-

The first drawing of the South Island takahē from Gideon and Walter Mantell's report in 1850.

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |