Spanish–Chamorro Wars facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Spanish–Chamorro Wars |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Habsburg Spain Pro-Spanish Chamorros |

Anti-colonist Chamorros | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Diego Luis de San Vitores (1670-1672) † Damián de Esplana (1674-1676) Antonio de Ayhi Francisco de Irrisari (1676-1679) José de Quiroga y Losada (1679-1697) |

Hurao (1670-1672) Matå'pang (1670-1680) (DOW) Agualin (1676-1679) † Yura (1684) |

||||||

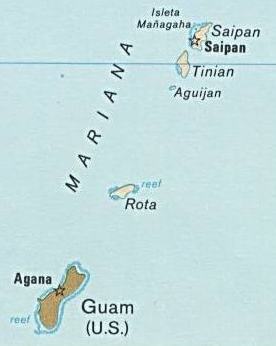

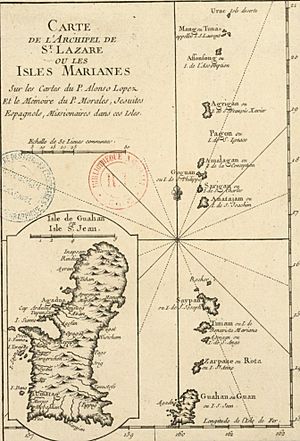

The Spanish–Chamorro Wars were a series of conflicts in the late 1600s. They involved the Chamorros of the Mariana Islands in the western Pacific Ocean and the Spanish. Spain was trying to take control of the islands.

Problems began when the first permanent Spanish mission arrived on Guam in 1668. This mission was led by Diego Luis de San Vitores. Cultural differences and the Spanish efforts to change Chamorro beliefs caused a lot of anger. In 1670, Chamorros attacked the Spanish fort in Hagåtña. This attack was led by Chief Hurao.

In 1672, Chief Matå'pang killed San Vitores. This led to Spanish attacks on Chamorro villages until 1676. These attacks made the Chamorros even angrier. Another rebellion started, led by Agualin, and Hagåtña was attacked again. Governor Juan Antonio de Salas then started a plan to make Chamorros cooperate. People who helped the Spanish were rewarded. Most Chamorros were moved from about 180 villages into seven larger towns. This policy was called reducción. By the early 1680s, Guam was mostly peaceful.

After controlling Guam, the Spanish wanted to control the Northern Mariana Islands. In 1680, Spanish forces quickly took over Rota. Its people were moved into two towns by 1682. The Spanish were welcomed on Tinian. But they had to fight against people on Saipan. After defeating the resisting villages, the Spanish began building a fort on Saipan.

However, while most Spanish soldiers were in the north, Guam rebelled again. Yula led a surprise attack on the Hagåtña fort on July 13, 1683. He killed the Jesuit leader and wounded Governor Damián de Esplana. A larger group of Chamorros then started the third attack on Hagåtña. At the same time, warriors from Tinian and Saipan attacked the Spanish on Saipan. The Spanish leader, Quiroga, had to hide in his unfinished fort. He was trapped until November. Then he escaped to Guam and ended the attack on Hagåtña. The Spanish then fought against resisting villages on Guam. They executed rebels until peace returned.

The Spanish did not try to control the northern islands again until 1694. Quiroga captured Saipan. But the people of Tinian had hidden on Aguiguan and fought back. After winning, Quiroga ordered the people of Tinian to move to Guam. Some escaped to islands further north, but Tinian soon became empty. The final step was a military trip in 1698 to the eight small islands at the northern end of the Marianas. Their people were moved to Guam in 1699. This completed the Spanish control of the Marianas.

Contents

- Early Chamorro Life and Spanish Arrival

- The "Poison Waters" Rumor

- First Attack on Hagatña (1670)

- San Vitores is Killed (1672)

- Spanish Fight Back (1674-1676)

- Second Attack on Hagatña (1676-1677)

- Spanish Control Strengthens (1678)

- Peace on Guam (1680-1681)

- Rota Becomes Peaceful (1680-1682)

- Last Major Resistance (1683)

- Final Control of the Islands

- See Also

Early Chamorro Life and Spanish Arrival

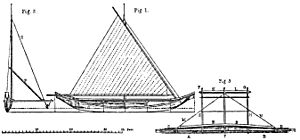

The ancient Chamorros lived in family groups. Their society had three main classes. Chamorro sailing skills and their fast sakman boats amazed the first Spanish sailors. In 1668, Guam had about 180 independent villages. The island's population was between 35,000 and 50,000 people.

There is not much proof of large wars among ancient Chamorros. Their weapons included the sling and spears. Chamorro boys and young men practiced with these weapons. Early European reports said Chamorro fights were small and disorganized. They often started over small arguments, like cut food trees.

Ferdinand Magellan was the first European to reach the Marianas in 1521. But Spain did not officially claim the islands until 1565. This was done by Miguel López de Legazpi. After this, Guam became a stop for the valuable Manila galleon trade. These ships carried silver from New Spain to trade for silk and porcelain from China. However, few galleons actually stopped at Guam. They mostly traded for water and food with Chamorros who came out in their sakman boats.

A permanent Spanish presence began on June 15, 1668. Father Diego Luis de San Vitores landed at Hagåtña. He led a group of 31 people, including five other Jesuit missionaries. San Vitores believed that bringing many soldiers would cause more problems. He thought Chamorros were peaceful.

When they arrived, local chiefs wanted the mission in their villages. Chief Kepuha of Hagåtña held a feast. The Spanish gave iron hoops to the chiefs for food. The missionaries baptized 23 islanders, mostly young children. The mission set up its main base in Hagåtña. It included the first version of the Dulce Nombre de Maria Cathedral Basilica. San Vitores did not want walls or forts. He believed in a message of peace. In January 1669, the first stone church was built in Hagåtña. A school for boys also opened. This was the first formal school in the Pacific.

Soon after arriving, a Chamorro threatened a Mexican mission helper. The helper was trying to destroy a shrine of ancestral skulls. The Spanish did not record much about Chamorro beliefs. But scholars think they honored ancestor spirits. Chamorros sometimes asked a makana for help. The Spanish called these makanas "sorcerers." The Spanish tried to destroy skull shrines and weaken the makanas' power.

The "Poison Waters" Rumor

The first violence against the mission happened in August 1668. Missionary Fr. Morales was attacked on Tinian and hurt. Five days later, two men with Fr. Morales were killed. They were attacked by Chamorros while traveling in sakmans. On Guam, Fr. Luis de Medina was badly beaten. This happened when he visited a distant village. Missionaries found that villages that had welcomed them before were now hiding paths. They refused to give traditional food and met the Spanish with weapons.

The Spanish blamed this anger on rumors. A Chinese castaway named Choco on Saipan spread a story. He said the water used for baptism by the missionaries was poisoned. This story seemed believable to villagers. Their only contact with missionaries was baptisms of the very sick or newborns. These groups had high death rates. Spanish records say that Chamorros in areas like Hagåtña, who knew the mission better, did not believe these stories.

This violence made San Vitores change his mind about using force. He asked the Philippines for 200 more armed men. He also asked that Manila galleons be ready to help. In late 1669, San Vitores led a group to Tinian. They tried to stop a war between two villages. When one group attacked the mission party, three Chamorros were killed by a small cannon. This was the first time the Spanish directly killed Chamorros.

In early 1670, Fr. Medina and his helper were killed on Saipan. They were preparing to baptize a sick child. Then, in July 1671, a Mexican mission helper in Hagatña was killed. He was cutting wood outside the village. The Spanish arrested suspects. They accidentally killed a Chamorro noble. The Chamorros did not understand the idea of a trial. One historian wrote that they were so offended by justice, they would rather be killed without a trial.

First Attack on Hagatña (1670)

The anger over the trial and the attacks on Chamorro beliefs led to open resistance in Hagatña. Hurao, a high-ranking Chamorro from the village, began gathering people to fight the Spanish.

In response, the Spanish built a wooden fort with two towers. About 2,000 Chamorro men soon faced them. But the Spanish quickly captured Hurao. The Spanish military leader wanted to attack. But San Vitores wanted to offer gifts of food. The Chamorros mostly fought in their traditional way. This involved showing strength and avoiding big battles. After a month, a strong typhoon ended the attack. The storm caused more deaths than the fighting. During the whole attack, only five Chamorros died.

For five months after the attack, San Vitores asked for more troops. He also worked harder to spread his mission to the northern islands. He seemed to believe that more soldiers would bring peace. The Spanish did not punish those who attacked the missionaries or Hagatña. Hurao was released from prison. He then traveled between villages, encouraging people to oppose the Spanish.

San Vitores is Killed (1672)

In March 1672, a young Mexican mission member was killed in Chochogo. This was a village known for resisting the Spanish. The next day, two Filipino helpers and their Spanish soldier guard were also killed in Chocogo. A few days later, San Vitores was returning to Hagåtña. He stopped in Tumon to find a mission helper.

In Tumon, San Vitores met Matå'pang. Matå'pang was a local elder whom San Vitores had helped when he was sick. But Matå'pang had turned against the Spanish. San Vitores offered to baptize Matå'pang's daughter. Matå'pang became very angry. He said he would kill San Vitores if he did not leave. When Matå'pang left to get weapons, San Vitores went into the house and baptized the girl. Matå'pang and his friend, said to be Hurao, caught and killed San Vitores and his helper, Pedro Calungsod.

In response, the Spanish attacked Tumon. They burned houses and sakmans. But the Spanish were attacked as they walked through Tumon Bay. They lost three soldiers. Two Chamorros were killed. A month later, Hurao was captured and killed by a Spanish soldier.

Fr. Francisco Solano became the mission head after San Vitores died. He continued peaceful policies. This was partly because the mission was weak. Only 21 of the original 31 helpers remained. They only had 13 muskets. Solano worried that if Chamorros knew how inaccurate the muskets were, they would overwhelm the mission. He told mission staff not to visit northern Guam, which was dangerous. Two more Filipinos were killed on Rota a month later. Solano then died from tuberculosis, just two months after San Vitores.

Spanish Fight Back (1674-1676)

After the events of 1672, 1673 was calm. But in February 1674, Fr. Francisco Ezquerra and five of his six companions were killed. This happened while they walked from Umatac to Fuuna. Spanish forces changed their approach in June 1674. Damián de Esplana arrived from a Manila galleon. He was a trained military officer. Esplana was immediately put in charge of the 21 militia soldiers.

Unlike the Jesuit leaders before him, Esplana believed in punishment. He thought it would warn the Chamorros. His first action was to threaten Chochogo, a center of resistance. He said they must allow mission access. The Chamorros refused. Esplana ordered a night attack. Several people were killed. Two weeks later, the Spanish attacked Chochogo again. They burned houses and destroyed spears. In November 1674, Esplana went to Tumon. The village was empty.

In January 1675, Esplana attacked northern Guam. He burned the resisting villages of Sidia and Ati. Esplana joined with Chief Antonio Ayhi's forces. They destroyed Sagua, whose villagers had killed a Jesuit. Esplana continued south. He burned Nagan and Hinca, which were involved in another Jesuit's death. Chamorros tried to ambush the Spanish near Merizo. But Esplana killed one Chamorro. He then captured and executed the chief of Tachuch as a warning. The Jesuits praised Esplana. He was seen as the mission's savior. In 1675, 20 more Spanish troops arrived on Guam.

In December 1675, a Jesuit and two helpers were killed at Ritidian. This happened after they scolded young men trying to enter a girls' dormitory. The men at Ritidian also burned all mission buildings. The Spanish recorded that older villagers did not approve but could not stop them. The next month, a Jesuit was killed in Upi. A Chamorro man accused him of cheating in a trade. In response, villagers from nearby Tarragui, who were close to the priest, challenged Upi to battle. The Tarragui force burned the killer's home and got the priest's body for burial. These events in northern Guam involved personal insults. There was also disagreement among Chamorros themselves.

In June 1676, Francisco de Irrisari arrived on Guam. He became the first Governor of the Mariana Islands. He took full control of military and civil matters. He also brought fourteen more soldiers. This made the garrison over 50 men. Irrisari continued Esplana's tactics. He marched on Talisay and killed five people in a daylight attack. A few weeks later, the garrison stopped a revolt in Orote. It started when a Chamorro girl from a mission school married a Spanish soldier against her father's wishes. Irrisari hanged the father for causing the revolt. He brought the couple to Hagatña for safety.

Second Attack on Hagatña (1676-1677)

By this time, the Spanish attacks on villages were the main reason for Chamorro anger. In late summer 1676, Agualin, a blind, high-ranking Chamorro from Hagåtña, began gathering resistance. He was like Hurao five years earlier.

Around this time, Antonio Ayhi became known as the most pro-Spanish chief. Ayhi made sure his village stayed loyal. He tried to stop anti-Spanish Chamorros from passing through. Other pro-Spanish chiefs included Ignacio Hineti of Sinajana and Alonso So'on of Agat. They led groups supporting Spanish attacks on hostile villages. By now, at least four villages on Guam had mission schools. Their students were often very loyal to the Spanish. Spanish soldiers had also started marrying Chamorro women. This increased the number of Chamorros with ties to the mission.

In late August 1676, Chamorro rebels set fire to the church and mission buildings at Ayra'an. A force led by Irrisari responded. They left eight soldiers to protect missionaries at Orote. A week later, the Orote pastor and soldiers were attacked. A local man named Cheref offered to take the Spanish to safety in his sakman. Once the Spanish were far from shore, Cheref and his men overturned the boat and attacked them. This event made the Spanish unsure who among the Chamorros could be trusted.

In response, the Spanish strengthened the walls of the Hagåtña fort. They built new guard posts and changed building layouts for better safety. Antonio Ayhi arrived with his men to help defend. But the Spanish told him to leave to protect his village. In mid-October 1676, Agualin led 1,500 men to the fort. It was defended by 40 Spanish soldiers with 18 muskets. The attack was similar to the first one. Chamorros stood outside musket range, taunting their enemies. The Spanish would sometimes charge out, killing a few Chamorros. The attackers would then flee to the hills, only to return. The Chamorros destroyed a cornfield that fed the mission. But the Spanish grew enough crops inside the fort to survive. The defenders easily stopped attempts to storm the fort. In January 1677, the Chamorro force left. Agualin avoided the Spanish until 1679. He was recognized while landing a sakman and killed. During the attack, Antonio Ayhi and other pro-Spanish leaders tried to bring food to the trapped mission.

Spanish Control Strengthens (1678)

In June 1678, a new governor, Juan Antonio de Salas, arrived with thirty more soldiers. He immediately started attacking resisting villages again. Salas attacked Apoto and Tupalao, burning them completely. The Spanish met resistance at Fuuna. They killed an unknown number of men before burning homes. Salas continued to Orote and Sumay, both centers of resistance. He burned both before going to Talofofo and Picpuc.

During their campaign, the Spanish told the people that Chamorros must turn in any murderers or rebels. If these rules were not followed, the village would be punished as a group. Following the rules would bring special recognition and titles. This was very appealing to the Chamorros. Their traditional culture used similar signs of status. Often, the Spanish would name someone as captain of the village police. They would give them a wooden staff. The new captain would then choose men he trusted as corporals. This created a police force like the Spanish military. These village forces were then expected to help stop revolts in other villages. The Jesuits wrote that Chamorros accepted the rules easily. Some hoped to gain favor with the Spanish. Others wanted forgiveness for crimes. All hoped for a reward.

These new rewards soon led to dozens of "criminals" being turned in. The Chamorro resistance was mostly broken. The remaining rebels went into hiding.

Peace on Guam (1680-1681)

In June 1680, a Jesuit wrote that Guam had been "quiet for more than a year." But priests still needed armed guards for safety and to ensure people obeyed. He wrote that people only listened out of fear. In late 1679, two priests with 40 Spanish troops and 40 armed Chamorro allies left Hagåtña. They visited villages that had not seen a Spanish visitor since 1676. Everywhere they went, the Spanish burned houses of young men. They baptized children and chose children to attend the mission school in Hagåtña. Many villages were empty because residents feared punishment. But most were brought back with promises of safety. The Spanish were welcomed in towns like Tarragui and Ritidian. Some villages, like Hanum, refused to obey. The Spanish burned some houses in return.

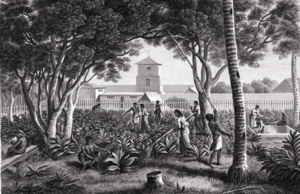

The Jesuits were happy with the pro-Spanish and pro-Christian changes. Most islanders were going to church. They regularly brought children for baptism and bodies for burial. These had been major problems in 1670. The church in Hagåtña was moved outside the fort walls. It was built to hold 1,000 people. The Spanish also largely succeeded in gathering the population. Residents of seven rural villages near Hagåtña were convinced to settle near the fort. This created the areas of Sinajana, Anigua, and Santa Cruz. The entire town center was enclosed in a wall, first wood, then stone. Outside Hagåtña, the Spanish policy of reducción gathered Chamorros into six towns. Each had about 1,000 residents. These towns were Pago, Agat, Inarajan, Umatac, Inapsan, and Mapupun. Each town had a church. They were built in orderly rows as the Spanish directed. Still, the Spanish burned houses outside these villages to stop people from settling without permission. This created the lanchu system. In this system, people lived in towns but worked on distant farms. The gathering of people into larger settlements seemed to speed up the spread of deadly foreign diseases. From 1680 to 1683, 917 deaths were recorded on Guam and Rota. This was compared to about twenty Chamorro deaths from fighting in the same period.

Salas left unexpectedly in 1680. José de Quiroga y Losada, a junior military officer, took command. A year passed peacefully. Antonio de Saravia arrived in June 1681. Unlike earlier leaders, Saravia was appointed governor by the King of Spain. This meant Guam was no longer under the Philippines or Mexico. As the first official governor, Saravia appointed Antonio Ayhi as lieutenant-governor. He gave him the title maestre-de-campo, like a colonel. Ayhi then convinced other major village chiefs to promise loyalty to Saravia on September 8, 1681. These chiefs then represented the governor in their regions. They later became mayors and other officials for the Spanish. Saravia built new roads, taught new skills, and brought new animals like chickens and cattle.

A big problem for the Spanish was the behavior of the soldiers. Since Esplana arrived, soldiers had started acting on their own. New recruits were often not well trained. Some were criminals who chose military duty on Guam over prison in the Philippines. In 1680, the number of soldiers grew to 115. But there was only enough pay for 40 soldiers. This meant each soldier earned only a third of their expected salary. This led to low spirits, soldiers trying to find money in any way, and general bad behavior. The Jesuits were grateful for the soldiers at first. But they became more and more shocked by the soldiers' actions. One Jesuit wrote in 1680, "The thefts that the soldiers have carried out among the Indians, and the other extortions, have been endless." Chamorro anger at the soldiers' bad behavior grew over the years.

Rota Becomes Peaceful (1680-1682)

With Guam peaceful, the Spanish focused on controlling the northern islands. In late 1680, Quiroga led forces to Rota. He captured several rebel leaders, who were later executed. He also sent up to 150 refugees from Guam back home. In April 1681, rebels from Inapsan, who had burned their church, fled to Rota. Quiroga followed them. With local help, he drove the rebels into the hills until most surrendered.

The Spanish then began gathering the people of Rota into towns, like they did on Guam. In March 1682, a church was built at Sosa (modern day Songsong). A second town was built at Agusan. The people were mostly moved into these two towns. But there was still some resistance. A spear was thrown at the Sosa church door. The church in Agusan was burned twice that year. However, the Agusan priest felt confident. He wrote that the dead received Christian burials, and the sick were brought to church for sacraments.

With Rota under control, the Spanish looked further north. In early 1682, the mission leader, Fr. Manuel Solorzano, took soldiers on a trip north. On Tinian and Aguigan, Solorzano baptized 300 babies. But his group was almost ambushed on Saipan. They achieved little there before bad winds forced them back to Guam. Twice in 1683, Saravia tried to lead Jesuit missions north. But the Spanish boats could not handle the rough weather.

Last Major Resistance (1683)

Governor Saravia died in November 1683. Damián de Esplana, who had returned to Guam, became the next governor. Esplana immediately ordered Quiroga north to conquer Tinian and Saipan. In March 1684, Quiroga's force of 76 Spanish soldiers and many Chamorro allies left Hagåtña. They were welcomed on Tinian. But they met strong resistance on Saipan. Many sakmans stopped an easy landing. One or two Saipanese warriors and a Spanish soldier were killed. The local Chamorros were forced to flee inland. Moving north, the Spanish burned the few villages that still resisted. The force then crossed the island and moved south. Only the village of Araiao fought back strongly. But their warriors were soon defeated. The Spanish claimed the head of one of the leaders. The campaign ended. Quiroga sent 25 soldiers to force the submission of the less populated islands further north. He began building a fort on Saipan.

However, the smaller number of soldiers in Hagåtña tempted the rebels still on Guam. Chief Yula (Yura) of Apurguan, near Tamuning, gathered other rebels. News of the rebellion spread quickly. By chance, most village priests were on their way to Hagåtña for a meeting. They avoided being caught in the uprising. However, many Chamorros on Guam sided with the Spanish. The rebels tried to convince Ignacio Hineti to join them, but he refused. The boys attending mission school often sided with the priests and soldiers.

On July 13, 1683, Yula and about 40 others hid weapons. They entered the fort pretending to attend mass. They killed the guards, left an injured Esplana for dead, and killed two Jesuit priests. In total, four Spanish soldiers were killed and 17 badly wounded. But they managed to kill Yula and drive away the rebels.

An even larger force of rebels returned a few days later. They tried to take the fort. But they met defenders helped by Ignacio Hineti and his Chamorro allies. Hineti killed the new rebel leader. However, the attackers managed to burn the church and rectory. They threatened to climb the walls. The Jesuits armed themselves to defend the fort. They eventually forced the attackers to leave by sakman. The rebels then encouraged Chamorros on Guam and in the northern islands to join the rebellion.

On Saipan, Quiroga did not know about the rebellion. He found out when the seventeen soldiers he had left on Tinian were killed and their boats burned. A combined force of Chamorro warriors from Tinian and Saipan attacked. They drove Quiroga's force into the unfinished fort. Quiroga's counterattack forced the enemy to flee. But the rebels soon returned. They attacked the fort for weeks. They made three strong charges to break through Spanish lines. Quiroga lost four soldiers. The Chamorros had "considerable losses." At this point, the Spanish force had 35 soldiers, from an original 75. Quiroga eventually managed to sneak to the shore. He took sakmans back to Guam in November 1683.

The third attack on Hagåtña had lasted four months when Quiroga arrived. There had been intense fighting in late July and August. At least five Filipino soldiers who had married Chamorro women had left. The injured Governor Espana had become unsure. It was likely only because of the pro-Spanish Chamorro militia that the fort had held out against the much larger attacking force. However, Quiroga had a fearsome reputation. The rebels abandoned the attack when he arrived. For months afterward, Quiroga chased the rebels. He burned more villages and executed prisoners. Finally, a tired peace was established again. This latest period of violence resulted in the loss of about a third of the Spanish soldiers, between 45 and 50. Perhaps 30 or 35 Chamorro rebels were also lost.

Final Control of the Islands

Esplana became very paranoid after almost being killed in 1684. He ordered soldiers to "shoot at sight any enemy islander." Esplana used his position to make money from the galleon trade. In 1688, Esplana suddenly left for Manila. Quiroga became temporary governor. He disciplined soldiers to make them change their ways. The angry soldiers rebelled and put Quiroga in a cell. Only the pleading of the Jesuit mission leader stopped the soldiers from executing Quiroga and got him released. Esplana returned the next year. But he mostly lived in Umatac while working on his shipping plans.

Eventually, the soldiers agreed to the missionaries' demands to finish conquering the northern islands. In early 1691, Esplana, Quiroga, and 80 soldiers sailed to Rota. The visibly shaking governor pleaded with the people for peace. Then he ordered the expedition back to Guam. This convinced the Jesuits that Esplana could not bring the rest of the Marianas under control. Nevertheless, by 1689, the number of Spanish troops increased to 160. The Marianas mission reached its largest size of twenty Jesuits. Meanwhile, the Chamorro population of Guam continued to suffer from foreign diseases. In 1689, the population, which was 35,000 to 50,000 before San Vitores, had fallen to below 10,000.

Esplana died in August 1694. Quiroga used his position as temporary governor to finally conquer the Marianas. In September, Quiroga and 50 soldiers sailed to Rota. They chased the residents of a resisting village into the mountains until they gave up. The Spanish destroyed their weapons. They moved 26 sakmans full of people to Guam. In July 1696, Quiroga and 80 troops, including Chamorro militia, sailed to Tinian. However, the residents had taken refuge on the large, mountainous island of Aguiguan. Several Spanish soldiers were killed trying to approach. Quiroga went back to Saipan. He waited for 20 sakmans of Chamorro militia to catch up. On Saipan, Quiroga met little resistance. He chased Saipanese warriors for days. But he also told the people he would not seek revenge if they allowed missionaries to work on the islands in the future.

When he returned to Tinian with his Chamorro allies, Quiroga found that everyone had gone to Aguiguan. Quiroga made the same offer to the people of Tinian as he had on Saipan. But they did not respond. He then burned the houses on Tinian as a warning, but still got no response. The Spanish then blocked Aguiguan so the refugees could not get food or water. Finally, they attacked the island directly. No defenders resisted once the Spanish reached high ground. Several people involved in a priest's murder were executed. Quiroga announced that all people of Tinian must move to Guam. Some people from Tinian fled to the northern islands to escape Spanish control. But no one dared stay on Tinian, and the island was soon empty.

More than 300 of the 2,000 people who lived in Gani, the eight small islands at the top of the Marianas chain, had been moved to Saipan. The Jesuit priest on Saipan realized that people from Gani were sneaking back to their home islands. He asked the new governor in Guam, José Madrazo, to finish controlling the north. In September 1698, 12 Spanish soldiers and a fleet of 112 Chamorro sakmans sailed to Gani. The people of Gani were amazed by the large force. They agreed to do whatever the Spanish wanted. 1,900 residents of Gani were moved, some temporarily to Saipan. They were finally settled in southern Guam in 1699. This completed the process of violence and moving people into towns, which had started 29 years earlier.

See Also

In Spanish: Guerras chamorras para niños

In Spanish: Guerras chamorras para niños

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |