St Melangell's Church facts for kids

Quick facts for kids St Melangell's Church |

|

|---|---|

Church and churchyard

|

|

| 52°49′39″N 3°26′59″W / 52.82750°N 3.44972°W | |

| Location | Pennant Melangell, Llangynog, Powys |

| Country | Wales |

| Denomination | Church in Wales |

| Administration | |

| Parish | Mission Area of Tanat-Vyrnwy |

| Deanery | Mathrafal |

| Diocese | St Asaph |

St Melangell's Church is a very old stone church in Powys, Wales. It is a special building because it is a Grade I listed site. This means it is very important and protected. The church was built to remember Melangell, a saint who lived there long ago. She was a hermit (someone who lives alone for religious reasons) and started a safe place for people.

The church you see today was built in the 12th century. It has been repaired and updated many times. In the 1980s, the church was almost torn down. But new leaders helped fix it up. They also started a special support group for people with cancer. Digs by archaeologists in 1958 and from 1987 to 1994 found many old things. These finds showed that people lived and were buried there even in the Bronze Age.

Inside St Melangell's Church, there is a special shrine to Saint Melangell. It is thought to be the oldest shrine of its kind in northern Europe. The shrine was built in the 12th century. It was a very popular place for people to visit until the Reformation. The Reformation was a time when many religious changes happened. The shrine was taken apart then. But it was put back together in 1958 using old pieces found nearby. It was fixed again in 1991. Even today, many people visit Pennant Melangell. They come for different reasons, like faith or history.

The church is made of different kinds of stone. It has a main hall (called a nave) and a square tower. At the east end is a rounded part called an apse. This part is known as the cell-y-bedd, which means "grave chamber" in Welsh. It is believed to be where Melangell was buried. The church has many old and valuable items inside. These include a wooden screen from the 15th century. This screen shows the story of Melangell. There are also two stone statues from the 14th century. The churchyard has thousands of graves. Most of them do not have names on them. There are also several old yew trees.

Where is St Melangell's Church?

Pennant Melangell is in the Tanat Valley. This area is close to the Berwyn Mountains. The church is in the village of Llangynog. You can only get to the church by a small road from Llangynog. This road follows the Afon Tanat river. This makes the church feel very quiet and far away.

In 1994, the land around the church was owned by private people. But for a long time before that, it was church land. This land helped support the church leaders. Old buildings like sheep pens and huts show how the land was used. People used it for grazing animals in summer. They also cut peat (a type of fuel) there.

Other old places are nearby. There is an old farm and what is left of a medieval village. There is also a natural rock shelf called Gwely Melangell. This means "Melangell's Bed". Someone carved "St Monacella's Bed" into the stone a long time ago. About a kilometre north of the church is a holy well. It is called Ffynnon Cwm Ewyn. People used to believe its water could help with certain illnesses.

Church History

The area where St Melangell's Church stands has been important for a very long time. It was a special place even in the Bronze Age. Later, early Christians probably made it a holy site. Archaeologists found signs of cremation pyres from the Bronze Age. This suggests there was a burial mound there. They also found Bronze Age pottery. This shows the site was used for burials before the church was built.

Medieval Times

The story of Saint Melangell says she came to Pennant to escape a marriage. She lived alone for 15 years. One day, a prince named Brochwel was hunting a hare. The hare ran and hid under Melangell's clothes. The prince was amazed. He gave her the land and said it would always be a safe place for anyone who needed it. Melangell then started a group of nuns there.

Pennant Melangell was likely founded in the late 700s. Later, there might have been a community of monks too. But by the 1200s, neither group was still there. The first written records of the church appeared in the 1200s. People in the area used to refuse to kill hares. This was because hares were linked to Melangell. Some experts think this respect for hares might come from older Celtic beliefs.

When the Normans took over Wales in the 11th and 12th centuries, they changed the Welsh Church. They brought back interest in saints, including Melangell. Before the current stone church, there might have been a wooden church. The stone church was built in the 12th century. It was probably built over an old graveyard. This graveyard was on top of a Bronze Age burial mound. The shrine to Melangell was also built in the 12th century. It was likely made by local people with Norman ideas. Historians believe the shrine was put up around 1160–1170. It was meant to hold Melangell's bones. The rounded apse part of the church was built around her original grave.

The church might have been built by a nobleman named Rhirid Flaidd. The first written records of the church are from 1254. They show the church was not very valuable then. But by 1291, it was one of the richer churches. This was probably because Melangell's popularity grew. By the 1400s, people visited the shrine to be cured of illnesses. The church roof was probably replaced in the 1400s. The beautiful wooden screen was also added then.

Changes During the Reformation

Melangell's shrine was very popular until the Reformation. In 1535, the money from offerings at the shrine was similar to other big shrines in Wales. But during the Reformation, King Henry VIII and later rulers changed religion in England and Wales. They stopped pilgrimages and honoring saints. This caused big changes to the church. The shrine was probably taken apart around this time. Parts of it were used in the church walls and the lychgate. A lychgate is a covered gate at the entrance to a churchyard. By the 1660s, the church was not as valuable anymore. The walls were covered with plaster. Seats were added to the church from the late 1500s.

Many repairs happened in the 1700s. Doors and windows were blocked up. A new porch was built. The old cell-y-bedd was also built then. It replaced the medieval apse. It was probably used as a schoolroom. It was also a vestry, a room where church items are kept. Even though the shrine was gone, people still remembered Melangell. They still linked her to the cell-y-bedd.

Fixing Up the Church

The church tower you see today was built during repairs in 1876–1877. It replaced an older tower. In 1878, new pews (church benches) and an altar table were added. A yew tree was planted in the churchyard to celebrate the repairs. St Melangell's Church became part of the Llangynog parish in 1878.

After the 1800s repairs, the church was mostly forgotten. The building started to fall apart. There were not many people attending church, so there was little money. By 1954, the cell-y-bedd was in bad shape. Some people thought it should be torn down. But in 1958, it was repaired. The shrine was put back together based on old designs. More small repairs and digs happened inside the church.

By the 1980s, the church was again in danger of being destroyed. At this time, a priest named Paul Davies and his wife bought a cottage nearby. His wife had recovered from cancer. Davies was allowed to look after the church for free. He started a cancer help centre in their cottage. A full restoration of the church began in 1989. The apse was rebuilt. The shrine was moved to the main part of the church. The old stone statues were also moved. The church had no electricity or heating before this. Electricity was put in for the first time during these repairs. A special service was held on May 27, 1992, to celebrate the church being fixed.

After Paul Davies passed away in 1994, his wife Evelyn continued his work. She became the first "shrine guardian." This person looks after the church's special activities. Evelyn Davies was followed by Linda Mary Edwards in 2003 and Lynette Norman in 2011. The current shrine guardian is Christine Browne, who started in 2016.

Modern Pilgrimage

In the 21st century, Pennant Melangell still attracts many visitors. These visitors come for religious reasons or just for interest. A survey in 2004 found that people visited for spiritual, historical, or architectural reasons. Most visitors went to church at least once a year. But some did not go to church at all. Even non-churchgoers felt a spiritual connection to the place. Many of them prayed or lit candles. The church's quiet and beautiful location also drew visitors. It made them feel the place was sacred.

A study from 2013–2016 looked at prayers left by visitors. These were on prayer cards or in a prayer book. The prayers showed that people from many different faiths visit the shrine. These included Franciscan nuns, Baptists, Methodists, and Russian Orthodox people. Many prayers mentioned cancer. This shows the influence of the cancer support group. Other prayers were about Melangell herself, the holiness of the place, nature, and womanhood.

Digging Up History: Archaeological Finds

In 1958, the cell-y-bedd was partly dug up. This happened when the shrine was being rebuilt. Under the wooden floor, they found a cobblestone floor. A large stone slab was set into it. Under this slab, they found a grave with pebbles, soil, and bone pieces. The old foundations of the medieval apse were also found. More digging happened between 1989 and 1994. This was in the cell-y-bedd, the main church, and north of the church.

The digs from 1989–1994 in the cell-y-bedd showed signs of very old activity. They found small pits filled with soil, charcoal, and bone pieces. This showed that people were buried there by cremation. Tests showed these burials were from the Middle Bronze Age. These pits were found under several layers of medieval flooring. In total, 29 pits were found near the apse. Many had human bone pieces. Under the walls of the cell-y-bedd, they found the foundations of the medieval apse. This apse was round and from the 12th century. A large stone slab, possibly a grave, was also found. To the east of the cell-y-bedd, 13 graves were found. Some of these were older than the building. Some had human skeletons.

More digging inside the church also found signs of Middle Bronze Age burials. Seven pits were found under the west end of the church. They were like the ones at the east end. They had charcoal, burnt plants, and human remains. Pieces of Bronze Age pottery were also found. These included parts of a large pot. Early medieval burials were also found. These were from before the 12th-century church was built. At least 16 burials were found under the church. They dated from the church's building up to the 1700s. Other finds included medieval pottery, a glass bead, and a carved stone tool. A piece of a Romanesque candlestick was also found. It had a dragon head and was likely from the 12th century.

The north wall of the church was also dug up. This showed it was mostly built in the 12th century. Digging in the north churchyard found 25 or 26 possible graves. These were not known before. Their exact age is not certain, but they are probably older than the 1600s. Some graves had stones around them. One had many white quartz pebbles. No coffins were found. Only a few had skeletons. A round pit with charcoal and a possible posthole were also found. These might be from prehistoric times. In 1987, when dirt was removed from the east churchyard, more unknown graves were found. These had cobblestones and were from the mid-1700s to mid-1800s.

The Shrine of Melangell

The shrine of Melangell is thought to be the oldest surviving Romanesque shrine in northern Europe. It is a rebuilt version of the 12th-century original. It was made from pieces found in and around the church. We do not know exactly when it was taken apart. But it was probably during the Reformation. Many other shrines in England and Wales were destroyed then. Parts of the shrine were used in the 17th-century lychgate. They were also used in the church walls during repairs in the 1600s and 1700s.

People noticed the pieces of the shrine in the past. But they thought they were from an older church. In 1894, Worthington George Smith realized they were from a shrine. In 1958, the shrine was rebuilt in the cell-y-bedd. An architect named R. B. Heaton designed it. It included an altar and a reliquary (a container for holy items). The 1958 shrine was taken apart in 1989. It was rebuilt again in 1991 in the main part of the church. This was based on new ideas from experts.

The shrine is made of pieces of pinkish-grey and yellowish-grey sandstone. Many pieces are worn down by weather. Some pieces were not used in the 1991 rebuild. They are kept separately. Some pieces still have traces of white and dark red paint.

We do not have any pictures of the shrine before it was taken apart. There are also no other similar shrines from that time to compare it to. So, we learn what it looked like from the stone pieces. The designs on the shrine, like the "willow" and "half-pear" leaves, suggest a link to Ireland. These designs are similar to old Celtic patterns found in Ireland. The steep roof design of Melangell's shrine was also common for small holy boxes in medieval Ireland. The leaf designs might show the bramble bush where Prince Brochwel found Melangell and the hare.

Church Design and Features

The church has a single main hall (the nave). It has a chancel and a rounded apse at the east end. There is a tower at the west end. The building is made of different stones. These include pebbles, large slabs of sedimentary rock, and blocks of shale. Different parts of the church were built at different times. These times range from the 12th to the 20th centuries. The main roof is made of slate. The porch roof is black ceramic tile. The square tower from the 1800s has a pointed roof. On top is a small wooden belfry (bell tower). The current bell was made in 1918.

The Cell-y-bedd

The cell-y-bedd, or apse, might have been built to hold Melangell's holy items. It is at the east end of the church. People traditionally believe it was built over Melangell's grave. A stone slab marks the spot of her supposed grave. Melangell's holy items might have been placed there for visitors to honor. This slab might have been added in the 1700s.

Most of this part of the church was built in 1751. It replaced the medieval apse. It was a small, uneven rectangular room. It had one window and a fireplace. It was built from shale slabs and boulders. It had many blocked-up doorways and patched holes from past repairs. The inside walls were plastered and painted white.

The original cell-y-bedd was taken down in 1989. The current apse replaced it. The new apse was built to look as much like the original 12th-century apse as possible. It was made from local rounded boulders. A new concrete floor with a cobbled surface was also laid. The grave slab was placed on top. The apse has three rounded windows in a 12th-century style.

Inside the Church

Most of the things inside St Melangell's Church are typical for a small church. But it also has several old and special items. These include a 12th-century baptismal font (for baptisms). There is a chest from the 1600s. An 18th-century chalice (cup for communion) is also there. There is a pulpit (for sermons) from the early 1700s. An 18th-century candelabrum (candle holder) is also present. A large whale rib is also inside. No one knows why it is there. It might have been part of a harp. It is sometimes called Asen y gawres (the Giantess' rib) or Asen Melangell (Melangell's rib).

The church has had paintings and wall decorations throughout its history. Not all of them have lasted. The oldest known are traces of flower and geometric patterns. Most of these are from the 1200s. Some wall writings from the 1600s were found during the 1876–1877 repairs. But none of them are left now. A royal coat of arms from the Stuart family was also found. It was painted over with a Hanoverian coat of arms in the 1700s. This was later covered with plaster. Above the altar was a painting from 1791. It showed the Ten Commandments, the Apostles' Creed, and the Lord's Prayer in Welsh. This painting was later moved to the tympanum (a space above a doorway). An 1886 copy was placed on the altar. This protected the original. Fancy stenciled designs were also added around the chancel in the 1800s.

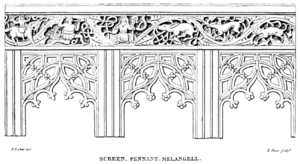

The Rood Screen

The carved wooden rood screen is from the late 1400s. It has the oldest picture of Melangell and the hare. Much of the original screen is gone. But what was left was fixed and put back together. This happened during the 1989–1992 work. The carvings on the screen show Prince Brochwel on his horse. They also show a hunter, Melangell, the hare, and two hunting dogs. There are traces of red, pink, yellow, brown, black, and blue paint on the screen. Melangell is shown as an abbess. She wears a veil and carries a crosier (a staff).

In 1848, an artist named John Parker described the carvings. He said they were "grotesque" but also clever. He noted how well the story was told. Below Melangell's carving are designs of acorns and oak leaves. The screen is carved from solid oak wood.

Stone Statues

The main part of the church has two stone statues from the 1300s. One is a man, and one is a woman. We do not know where they were originally. They were moved into the church in 1876. Before that, the male statue was in the churchyard. The female statue was missing.

The male statue shows a young man with a sword and shield. He is lying down with his head on cushions. An animal, possibly a wolf, is at his feet. The writing on his shield is hard to read now. We do not know who the man is. But some people think he is a nobleman from the 1100s, Iorwerth Drwyndwn. Others think he might be a member of Rhirid Flaidd's family. This is because of the wolf on his shield. The wolf was a symbol of that family. The female statue might be Iorwerth's wife, Gwerfyl. The male statue has been damaged. People sharpened knives on it and carved initials over time. An old vicar supposedly hit the statue's legs with a stone. This caused lasting damage.

The female statue is traditionally thought to be Melangell. But this is not certain. The figure wears a long dress and a square headdress. This style was common in the late 1300s. A lion is at her feet. Two other animals are on either side. These animals might be hares. If they are, the statue would likely be a holy figure of Melangell. The earliest known mention of this statue as Melangell is from 1773. Like the male statue, it has been damaged by knife sharpening. It is also broken into two parts.

The Churchyard

The churchyard of Pennant Melangell is mostly round. It is surrounded by a stone wall. This wall is probably much older than the first mentions of it in the 1700s. A detailed survey of the churchyard was done in 1986. It listed all the gravestones, trees, and mounds. Pictures and information about each gravestone were taken. The oldest marked graves are in the southeast, near the church. The earliest gravestone is from 1619. There are no visible graves in the north of the churchyard. People did not prefer to be buried there. But digs showed many burials happened there before the 1600s. Since burial records started in 1680, about 1,000 burials have been recorded. Most of these do not have names on them. Another 1,000–2,000 unmarked graves are believed to be there. These could be from as early as the 1100s. They include graves of visitors from other places. Three graves are for soldiers who died in World War I. The Welsh harpist Nansi Richards was also buried there.

The base of an old stone cross is among the gravestones. It might have been moved from near the lychgate. It is now used as the base for a sundial. North of the church is a mound. This might have been a preaching mound. There are seven yew trees in the churchyard. The largest one is 3.5 meters wide. Most of them are thought to be much older than the first written mentions in the 1700s.

The lychgate was probably built in the 1500s or 1600s. It used to have pieces of the original shrine. But these stones were removed in 1958. The gate has arched openings on both sides. It also has stone seats inside. A small piece of writing from when the gate was built is still there. Most of the writing is gone. But it was recorded in the 1700s. It read:

|

Tuedda 'n bur at Weddi |

Incline thyself in purity to Prayer, |

In the past, the churchyard was used for other things too. It was a place for games and festivals. The north churchyard was used for ball games until the 1800s. This might be why there are no graves there. It might also explain why there are no windows on the north wall of the church. Two old cockpits (places for cockfights) were also there. They were probably used until the 1800s. But they are not there anymore. Plays were also performed in the churchyard.

Images for kids

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |