Stairs Expedition to Katanga facts for kids

The Stairs Expedition to Katanga (1891−92) was a race between two powerful groups, the British South Africa Company (BSAC) and the Congo Free State. They both wanted to claim Katanga, a huge area in Central Africa rich in minerals. Captain William Stairs led the winning expedition.

This mission became famous for two main reasons: a local leader named Mwenda Msiri was killed, and Captain Stairs, who led one side, actually worked for the other side's army. This "scramble for Katanga" was a key event in the "Scramble for Africa" period, when European powers rushed to claim land on the African continent.

Contents

Why the Race Started

On one side was the Congo Free State, which was King Leopold II of Belgium's private way to colonize parts of Central Africa. On the other side was the BSAC, a company created by the British government. It was led by Cecil Rhodes, who wanted to find minerals and build a British empire across Africa, from Cape Town to Cairo.

Caught in the middle was Msiri, the powerful chief of Garanganze (also known as Katanga). His land was not yet claimed by any European power and was larger than many countries in Europe. Msiri was a clever leader. He had used better weapons, gained from trading ivory, copper, and slaves, to conquer other tribes. By the time Stairs arrived, Msiri was the strong ruler of the area. He was smart like the Europeans, but his army had older weapons.

The Berlin Conference Rules

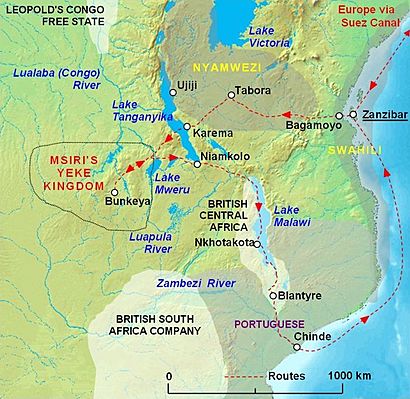

At the 1884–85 Berlin Conference, European countries decided how to divide Africa. The land west and north of the Luapula River and Lake Mweru (Katanga) was given to the Congo Free State. The land to the east and south went to Britain and the BSAC.

However, these agreements had a rule called the "Principle of Effectivity." This meant each colonial power had to actually be present in the territory. They had to make agreements with local chiefs, raise their flag, and set up a government and police. If they didn't, a rival could come in and claim the land. By 1890, neither side had fully claimed Katanga. When reports of gold and copper in Katanga spread, the race began.

Agreements with African chiefs were mostly to show other European powers that they had a right to the land. This was important because people in Europe were starting to have more say in what their governments did.

Earlier Attempts

Rhodes sent Alfred Sharpe from Nyasaland in 1890, with Joseph Thomson coming from the south. But Sharpe could not convince Msiri, and Thomson did not reach Msiri's capital. Sharpe thought their rivals would also fail. He believed Katanga would become British once Msiri, who was 60 years old, was gone.

King Leopold then sent two expeditions in 1891. The Paul Le Marinel expedition only got a vague letter from Msiri, allowing Free State agents to be in Katanga, but nothing more. This expedition had trouble when its gunpowder exploded. A Belgian officer, Legat, stayed behind near Msiri's capital.

The Delcommune Expedition followed, trying to get Msiri to accept the Free State flag. It also failed and went south to look for minerals.

Getting Ready and the Journey

The Team

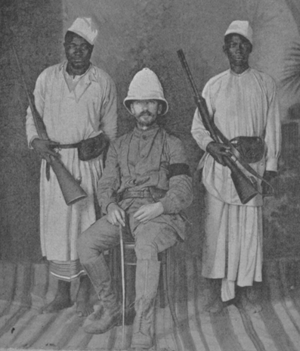

Belgium did not have many people with experience in tropical areas. But King Leopold was good at hiring people from other European countries. Henry Morton Stanley, a famous explorer, suggested Captain William Stairs to lead the expedition. Stairs was 27 years old and spoke Swahili. He had experience from a previous expedition where he was Stanley's second-in-command. Stairs was known for following orders and getting things done. He was Canadian but considered himself British.

Stairs' second-in-command was Captain Omer Bodson, the only Belgian. The third in command was the Marquis Christian de Bonchamps, a French adventurer. There were two other white men: Joseph Moloney, the doctor, who had also been on other expeditions, and Robinson, the carpenter.

Stairs knew it was a race and thought Joseph Thomson might reach Msiri first for the BSAC.

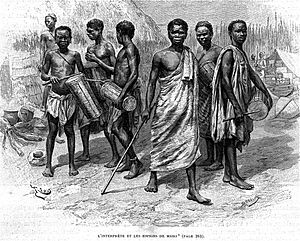

The expedition hired 400 Africans. These included four or five Zanzibari 'chiefs' or supervisors, like Hamadi bin Malum and Massoudi. About 100 were askaris (African soldiers), and the rest were porters. Most were from Zanzibar, some from Mombasa, and 40 were hired later in Tabora. The expedition also used eight tough Dahomeyan askaris who knew Msiri's capital well.

The askaris had 200 'Fusil Gras' rifles, a common French army weapon. The officers had several weapons, including Winchester rifles. Msiri's army had older muskets and needed gunpowder.

Goals of the Mission

Stairs' orders were to take Katanga, even if Msiri did not agree. If a BSAC expedition had already made a deal with Msiri, they were to wait for new orders. If Stairs got a treaty first and a BSAC expedition arrived, he was to tell them to leave. Stairs and Moloney were ready to use force if needed. They knew that Cecil Rhodes had used armed force to take land from the Portuguese in 1890.

After taking Katanga, they were to wait for a second Free State group, the Bia Expedition, coming from the north.

The Long Journey

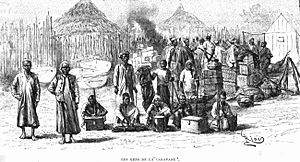

The expedition started from Zanzibar on June 27, 1891. They marched 1050 km across German East Africa to Lake Tanganyika. They crossed the lake by boat, then marched another 550 km to Bunkeya. The journey was tough, with extreme heat, humidity, and then chilling rain, mosquitoes, and unhealthy conditions.

They walked about 13.3 km each day, taking 120 days of marching over five months. The journey included thick forests, swamps, and rocky plains, but also beautiful landscapes and grasslands with lots of animals. The officers had donkeys to ride, but these died after crossing Lake Tanganyika. The expedition was not attacked by hostile tribes.

As they got closer to Bunkeya, they saw signs of famine and fighting. Many villages were burned and empty. Moloney thought this was because of Msiri's harsh rule. Other reports suggested that some chiefs Msiri had conquered were rebelling against him. Msiri was 60 years old, and people thought his rule was ending.

The expedition heard there were three Europeans in Bunkeya and thought Thomson had beaten them. But they found out they were Plymouth Brethren missionaries. Near Bunkeya, they met Legat, the officer from the earlier expedition, with his Dahomeyan askaris.

Meeting Msiri

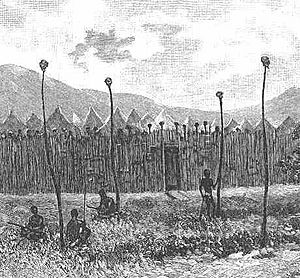

Msiri's capital, Bunkeya, was a very large compound surrounded by many villages. The expedition set up camp close by. Msiri had skulls of his enemies displayed on poles.

After a three-day wait, Msiri met them on December 17, 1891. They exchanged gifts and began talks. Msiri wanted gunpowder and for Legat to leave. Stairs wanted to raise the Free State flag over Bunkeya. Stairs thought a previous letter meant Msiri agreed, but Msiri said he did not.

During the talks, Msiri used drummers to spy on Stairs' camp, sending messages with talking drums.

On December 19, Stairs realized Msiri was just trying to delay things. Stairs was worried Thomson might arrive or that Msiri's 5000 warriors would return. So, Stairs gave Msiri an ultimatum: sign a treaty and perform a ceremony the next day, or Stairs would raise the Free State flag without his permission. Stairs then raised the flag.

Msiri's response was to leave that night for Munema, a fortified village outside Bunkeya. The next day, December 20, Stairs sent Bodson and Bonchamps with 100 askaris to bring Msiri back.

The Death of Msiri

At Munema, Bodson and Bonchamps found a large, guarded fence around many huts. Bodson decided to go inside with only ten askaris to find Msiri. Bonchamps and the rest waited outside.

Bodson found Msiri sitting in front of a hut with 300 men nearby, many with muskets. Bodson told Msiri he was there to take him to Stairs. Msiri became angry, stood up, and put his hand on his sword. Bodson then shot Msiri three times. One of Msiri's men, his son Masuka, fired his musket, hitting Bodson. The Dahomeyan askari then shot and killed Masuka.

Bonchamps and the other askaris rushed in. Most of Msiri's men ran away, and the askaris started looting. It took almost an hour for Moloney to arrive with more men. They brought order and retreated with Bodson, who was wounded, and Msiri's body. They took a defensive spot on a hill.

Moloney said this account came from Hamadi, and Bonchamps said Bodson told him the same before he died that night. Stairs also wrote a letter with similar details.

On the hill, the expedition showed Msiri's body to the people to prove he was dead. Bonchamps admitted this was harsh but said it was necessary.

What Happened Next

The expedition quickly made their defenses stronger. Msiri's brothers and his adopted son, Mukanda-Bantu, sent messages asking for the body to bury. Stairs agreed. After the burial, new talks began.

The expedition's weapons were much better than Msiri's muskets. Msiri's people were more interested in who would rule next than in revenge. Stairs supported Mukanda-Bantu to become the new chief, but of a smaller area. He also brought back the Wasanga chiefs Msiri had overthrown years ago. Mukanda-Bantu signed the treaties, and the Wasanga chiefs were happy to do so. Msiri's brothers were not happy with their new roles but signed after being threatened. By early January 1892, the expedition had the papers needed to show they had claimed Katanga.

In January, food ran out. The area was already suffering from famine, and people had taken what little food there was when they fled. The rainy season brought malaria and dysentery. All four surviving officers became sick. Floods cut off Bunkeya from areas where they could hunt. Moloney recovered first and took charge. 76 of the expedition's askaris and porters died that month from illness and hunger. Stairs had severe fevers and was very ill.

At the end of January, the new maize crop was ready, which saved the expedition. Then, the delayed Bia Expedition, with about 350 men, arrived from the north.

The Journey Home

Captain Stairs, the Marquis Bonchamps, and Robinson were still sick. So, Captain Bia took over control of Katanga for the Congo Free State. The Stairs expedition would return by a different route, through Lake Nyasa and the Zambezi River.

As they left, carrying the sick officers in hammocks, they faced some attacks from local people. The march was very hard due to heavy rains. Bonchamps recovered by the time they reached Lake Tanganyika and was put in charge by Stairs, who was still not fully well.

From the north end of Lake Nyasa, they traveled by steamer. They had to march about 150 km around rapids on the Shire River. Here, they passed Zomba and Blantyre, where Alfred Sharpe, the BSAC agent they had beaten in the race, was based. They met, but what they talked about was not written down.

On a second steamer down the Zambezi, Stairs, who seemed to have recovered, suddenly became sick again. He died on June 3, 1892, from a severe form of malaria. He was buried in a cemetery at Chinde.

The expedition reached Zanzibar a year after they had left. Out of 400 Africans who started from Tabora, only 189 reached Zanzibar. Most of the others had died, and a few had run away. Bonchamps, Moloney, and Robinson reached Europe just over 14 months after starting the expedition.

What Happened After

When Moloney returned to London, he learned that Thomson had not tried to reach Katanga again. The British Government had quietly told him not to go.

The expedition survived only because of the strength and loyalty of the Zanzibari porters and askaris.

Leopold and the Belgian Congo

The Belgians saw the expedition as a great success. King Leopold used his power to make sure the treaties were accepted. This added about half a million square kilometers to his territory, which was 16 times the size of Belgium. Leopold kept Katanga separate from the rest of the Congo Free State. This meant it was not linked to the terrible "Red Rubber" problems of Leopold's rule in other parts of the Congo. The company managing Katanga helped stop the slave trade but did little else until after 1900. Katanga remained unstable after Msiri's death.

The Belgian government took over Katanga and the Congo in 1908 because of international anger over Leopold's brutal rule. They were joined in 1910 as the Belgian Congo. But Katanga often tried to break away because of its earlier separate history.

Rhodes and the BSAC

Cecil Rhodes got over losing Katanga by investing in mineral prospecting and mining there. When the British in Rhodesia realized how rich Katanga was in minerals, Captain Stairs was sometimes called a "mercenary" or even a "traitor" to the British Empire.

The Garanganze People

The population around Bunkeya was 60,000 to 80,000, but most scattered after the fighting. The Belgians moved Mukanda-Bantu and about 10,000 of his people to the Lufoi River. They continued their leadership there, using the title 'Mwami Mwenda' to honor Msiri. They eventually returned to Bunkeya, where today Mwami Mwenda VIII is the chief of about 20,000 Yeke/Garanganze people.

Dan Crawford, the missionary, moved to the Luapula-Lake Mweru valley and set up two missions, where many Garanganze people went.

The DR Congo-Zambia Border

The Stairs Expedition helped decide that the border between the Belgian and British colonies would follow the Zambezi-Congo watershed, the Luapula River, Lake Mweru, and a line between Mweru and Lake Tanganyika. This divided people like the Kazembe-Lunda, who were culturally similar. This created the Congo Pedicle, showing how colonial borders were often drawn without considering local people.

The Mystery of Msiri's Head

In the traditional beliefs of the Garanganze people, sickness is caused by magic. The illness suffered by Stairs and his team was thought to be Msiri's spirit taking revenge. A rumor spread that Stairs had kept Msiri's head and that it cursed anyone who carried it. The history of the Mwami Mwenda chiefs says the expedition fled with Msiri's head to give to Leopold, but Msiri's men caught and killed the Belgians, and the head was buried "under a hill of stones" in what is now Zambia.

Another story says that when Stairs died, he had Msiri's head in a can of kerosene. However, Moloney's or Bonchamps' journals do not mention this. The location of Msiri's skull remains a mystery today.

See also