Tartessos facts for kids

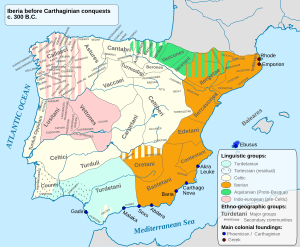

Tartessos (Spanish: Tartesos) was an ancient civilization. It lived in the southern part of the Iberian Peninsula (modern-day Spain). This culture mixed local ancient Spanish ways with ideas from the Phoenicians.

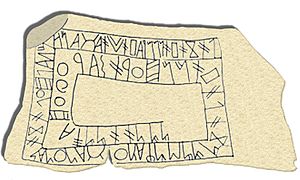

Tartessos had its own writing system. It is called Tartessian. We have found about 97 writings in the Tartessian language.

Ancient Greek and Near Eastern writings mention Tartessos. They describe it as a rich port city. It was located on the southern coast of Iberia. This is near the mouth of the Guadalquivir River in today's Andalusia, Spain. The Greek historian Herodotus said it was beyond the Pillars of Hercules. Later Roman writers also talked about Tartessos. But by the end of the first millennium BC, its name was not used much. The city might have been lost due to floods.

The people of Tartessos were very rich in metals. A historian named Ephorus wrote about Tartessos in the 4th century BC. He said it was a busy market. Much tin, gold, and copper came from there. Trading tin was very important in the Bronze Age. Tin was needed to make bronze and was hard to find. Herodotus also mentioned a king of Tartessos, Arganthonios. He was likely named for his great wealth in silver. Herodotus said King Arganthonios welcomed the first Greeks to Iberia. These were Phocaeans from Asia Minor.

Pausanias wrote about a treasury built by Myron. It was called the treasury of the Sicyonians. He said it was made with bronze. The Eleans, another ancient people, said this bronze came from Tartessos.

Tartessians became important trading partners with the Phoenicians. The Phoenicians arrived in Iberia around the 8th century BC. They built their own port nearby. It was called Gadir (Greek: Γάδειρα), now known as Cádiz.

Contents

Where Was Tartessos?

Some old writings, like those by Aristotle, say Tartessos was a river. Aristotle claimed it started in the Pyrene Mountain (the Pyrenees). Then it flowed into the sea outside the Pillars of Hercules. This is the modern Strait of Gibraltar. But no such river crosses the Iberian Peninsula.

The Greek explorer Pytheas (4th century BC) said Tartessos was in the Baetis River valley. This is the present-day Guadalquivir valley in southern Spain.

Pausanias, writing in the 2nd century AD, gave more details. He said: "They say that Tartessus is a river in the land of the Iberians, running down into the sea by two mouths and that between these two mouths lies a city of the same name. The river, which is the largest in Iberia and tidal, those of a later day called Baetis and there are some who think that Tartessus was the ancient name of Carpia, a city of the Iberians."

The river he called Baetis is now the Guadalquivir. So, Tartessos might be buried under the changing wetlands. A sandbar has slowly blocked the river delta. This area is now a protected place called the Parque Nacional de Doñana.

What Have Archaeologists Found?

In 1922, Adolf Schulten's discoveries brought attention to Tartessos. This made people study it using archaeology. Later, in September 1923, archaeologists found a Phoenician burial ground. They found human remains and stones with strange writing. Phoenicians might have settled there for trade. Tartessos was very rich in metals.

Later, archaeologists looked for "eastern" (Mediterranean) features in Tartessian items. This helped them understand the culture better.

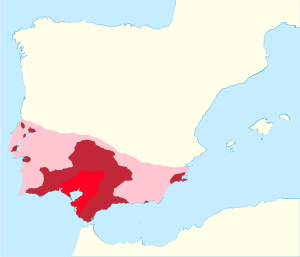

J. M. Luzón first linked Tartessos with modern Huelva. This was based on discoveries from past decades. In 1958, the rich gold treasure of El Carambolo was found near Seville. Hundreds of items were also found in the La Joya burial ground in Huelva. These finds helped us learn more about the Tartessian culture. It was mainly in western Andalusia, Extremadura, and southern Portugal.

Excavations started at the Turuñuelo site in 2015. This site was declared important in May 2022.

Tartessian streams had tin from early times. The use of silver as money in Assyria made silver more valuable. The invention of coins in the 7th century BC also increased the search for bronze and silver. This made trade more important for the economy. By the Late Bronze Age, silver mining in Huelva Province was huge. Old silver waste is found in Tartessian cities there.

"Tartessic" items linked to the Tartessos culture have been found. Many archaeologists now think the "lost" city is Huelva. In Huelva, pieces of fancy Greek pottery from the 6th century BC have been found. Huelva has the most imported luxury goods. It must have been a key Tartessian center. A significant burial ground was also found in Medellín.

Special Tartessian items include pottery with patterns. There are also "Carambolo" wares from the 9th to 6th centuries BC. An "Early Orientalizing" phase began around 750 BC. This is when the first items from the eastern Mediterranean arrived. A "Late Orientalizing" phase had the best bronze and gold work.

Typical Tartessian bronze items include pear-shaped jugs. These were often found in burials. There were also shallow braziers, incense-burners, and brooches.

Most sites were strangely left empty in the 5th century BC.

New finds in Huelva are changing old ideas. In a small area, about 90,000 pieces of pottery were found. These included local, Phoenician, and Greek items. This pottery dates from the 10th to early 8th centuries BC. This is older than finds from other Phoenician colonies. These discoveries show that Huelva was a big trading center for centuries.

Scientists have used carbon-14 dating on bones. They also dated ceramic samples. This shows a timeline of crafts and industry since the 10th century BC. They found pottery, melting pots, tools, wood pieces, and ship parts. They also found animal skulls, pendants, and items made of ivory, gold, and silver.

The mix of foreign and local items shows that Huelva's old harbor was a major hub. It received, made, and shipped many different products. Some experts think this place could be Tarshish from the Bible. They also think it could be the Tartessos from Greek writings.

Religion

We don't have much information about their religion. But like other Mediterranean people, they likely believed in many gods. It is thought that Tartessians worshipped the goddess Astarte or Potnia. They also worshipped the god Baal or Melkart. This was due to Phoenician influence. Temples like Phoenician ones have been found. Images of Phoenician gods have been found in Cádiz, Huelva, and Sevilla.

Language

The Tartessian language is an extinct language. It was spoken in southern Iberia before the Romans. The oldest known writings from Iberia are in Tartessian. They date from the 7th to 6th centuries BC. These writings use a special system called the Southwest script. They were found where Tartessos was located and nearby. Tartessian texts were found in Southwestern Spain and Southern Portugal.

Was Tartessos "Tarshish" or "Atlantis"?

Since the early 1900s, some experts have linked the biblical place-name Tarshish with Tartessos. Others think Tarshish was Tarsus in Turkey or even in India. Like Tartessos, Tarshish is known for its great metal wealth.

In 1922, Adolf Schulten suggested that Tartessos was the real place behind the legend of Atlantis. Both Atlantis and Tartessos were thought to be advanced societies. Both were believed to have collapsed when their cities were lost underwater. These similarities make some people think there's a connection. But we know almost nothing about Tartessos's exact location. Some Tartessian fans imagine it traded with Atlantis.

In 2011, a team led by Richard Freund claimed to find strong evidence. They said Tartessos was in Doñana National Park. They used surveys and thought the Cancho Roano site was a "memorial city" built like Atlantis. But Spanish scientists disagreed. They said Freund was making their work sound too exciting.

Simcha Jacobovici, who made a documentary on Freund's work, said that the biblical Tarshish (which he believes is Tartessos) was Atlantis. He claimed "Atlantis was hiding in the Tanach" (the Hebrew Bible). However, most archaeologists involved in the project strongly disagree with this idea.

See also

In Spanish: Tartessos para niños

In Spanish: Tartessos para niños

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |