The Trundle facts for kids

Quick facts for kids The Trundle |

|

|---|---|

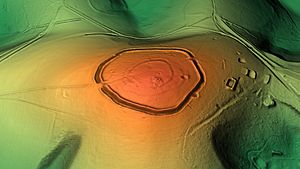

Rampart, ditch, and bank of the Trundle Iron Age hillfort

|

|

| Location | The Trundle in West Sussex, England |

| OS grid reference | SU87771103 |

| Area | 5.66 ha (14.0 acres) |

| Built | Iron Age |

| Official name: The Trundle hillfort, causewayed enclosure and associated remains at St Roche's Hill | |

| Designated | 23 February 1933 |

| Reference no. | 1018034 |

The Trundle is an ancient site on St Roche's Hill in West Sussex, England. It's about 4 miles (6.4 km) north of Chichester. This special place has two main parts: an Iron Age hillfort and an even older causewayed enclosure from the early Neolithic period.

People built causewayed enclosures in England between 3700 BC and 3500 BC. These were areas surrounded by ditches with gaps, like pathways, called causeways. We don't know exactly why they were built. They might have been settlements, meeting places, or even places for special ceremonies.

Later, around 1000 BC, people started building hillforts. These continued to be built through the Iron Age until the Romans arrived.

Over time, other things were built on the hill. A chapel for St Roche was built around the late 1300s, but it was in ruins by 1570. Later, a windmill and a beacon (a signal fire) were also built there. The hill was sometimes used as a meeting spot in more recent times.

The hillfort's earthworks are still very clear today. However, the older Neolithic site was a secret until 1925. That's when archaeologist O.G.S. Crawford took an aerial photograph of The Trundle. This photo clearly showed more structures inside the hillfort's walls.

At that time, causewayed enclosures were a new discovery in archaeology. Only five were known by 1930. The photograph convinced archaeologist E. Cecil Curwen to dig at the site in 1928 and 1930. These early digs helped figure out that the hillfort was built between 500 BC and 100 BC. They also proved that the Neolithic site existed.

In 2011, a project called "Gathering Time" looked at radiocarbon dates from many causewayed enclosures, including The Trundle. They concluded that the Neolithic part of the site was likely built around the middle of the fourth millennium BC. In 1995, a review by Alastair Oswald found fifteen possible Iron Age house platforms within the hillfort's walls.

Contents

What are Causewayed Enclosures and Hillforts?

The Trundle is an important archaeological site. It contains both a causewayed enclosure and an Iron Age hillfort. Understanding these two types of ancient structures helps us learn about the people who lived here long ago.

What is a Causewayed Enclosure?

Causewayed enclosures are a type of ancient earthwork. People built them in northwestern Europe, including southern Britain, during the early Neolithic period. These enclosures are areas partly or fully surrounded by ditches. These ditches have gaps, or "causeways," of untouched ground. Sometimes, they also had earthworks or palisades (fences made of strong wooden posts).

Historians and archaeologists have long debated what these enclosures were used for. The causeways are puzzling if you think of them as military forts. They would have made it easy for attackers to get inside. However, some suggest they might have been "sally ports" for defenders to rush out and attack.

Evidence of attacks at some sites suggests they might have been fortified settlements. They could also have been seasonal meeting places. People might have gathered there to trade cattle or other goods like pottery. There is also evidence that they were used for funeral ceremonies. Things like food, pottery, and even human remains were carefully placed in the ditches.

Building an enclosure took a lot of work and organization. People had to clear land, prepare trees for posts, and dig ditches. This shows that the early Neolithic communities worked together on big projects.

Over 70 causewayed enclosures are known in Britain. They are one of the most common types of early Neolithic sites in western Europe, with about a thousand known in total. They appeared at different times across Europe. In southern Britain, they began appearing just before 3700 BC. They continued to be built for at least 200 years. Some were even used as late as 3300 to 3200 BC.

What is an Iron Age Hillfort?

The Iron Age in Britain is usually split into two main periods. The earlier period, called the Hallstatt culture, lasted from about 800 BC to the fifth century BC. This was followed by the La Tène culture, which lasted until the Romans took over.

Hillforts started appearing in Britain in the Late Bronze Age. They continued to be built throughout most of the Iron Age. These are sites on hilltops with large walls or banks, called ramparts. These ramparts could be made of stone, timber, or earth.

Even though their name suggests they were only for defense, excavations show they had other uses. Some sites show signs of settlement, meaning people lived there. They might also have been important religious places. People and animals might have been kept safe inside the ramparts. There's also evidence that the entrances were designed to guide animals inside.

Unlike causewayed enclosures, hillforts usually have only one or two entrances. Thousands of hillforts have been found across Britain. After about 100 BC, another type of fortified settlement called an oppidum became more common.

Exploring The Trundle: Past Discoveries

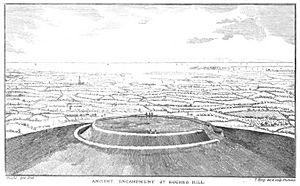

People have been interested in The Trundle for a long time. Early drawings and writings mention the site.

Early Drawings and Writings

In 1723, an etching of the hillfort was included in a book called Itinerarium Curiosum by William Stukeley. In 1804, Alexander Hay's History of Chichester mentioned "saint Roche's hill, commonly called Rook's hill." He noted that "on the top of which are the remains of a small camp, in a circular form." He thought the Danes might have built it when they attacked the area.

An 1835 history of Sussex discussed the hillfort. It gave reasons why it probably wasn't Roman or Danish. It concluded that the builders couldn't be known for sure. T. King, a local historian, drew a picture of the site in 1839.

By 1916, maps called the hillfort a "British Camp." This was the term used then for Iron Age hillforts. A historian named Allcroft gave reasons why he believed it was built before the Romans. Allcroft also thought the name "Trundle" came from an old Anglo-Saxon word for "hoop." However, later experts like Oswald said that people at that time often made mistakes when guessing word origins.

In 725 AD, Nunna, a king of Sussex, gave away land in the area. A document about this land mentioned "billingabyrig," which was a burh (a fortified settlement). Since The Trundle is the closest fortified site to other places named in the document, Curwen suggested in 1928 that they might be the same place. But he said it wasn't proven.

Curwen's Digs: 1928 and 1930

In the early 1900s, O.G.S. Crawford started taking aerial photos of archaeological sites. He realized these photos could show things hidden on the ground. In 1925, he arranged for a photo of The Trundle hillfort. The photo showed more circular earthworks inside the hillfort's walls. This made Crawford think the hillfort was built on top of an older Neolithic camp.

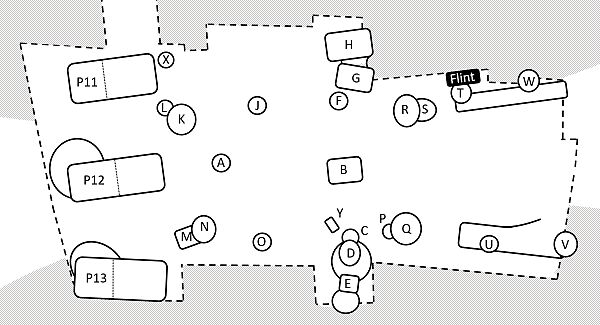

To test this idea, Curwen got permission from the Duke of Richmond, who owned the land. Curwen then dug at the site from August 7 to September 1, 1928.

Curwen made a map of the site. He used a tool called a boser to find the ditches and banks. A boser is a heavy tool used to find things underground by listening to the sound it makes. The map showed an inner circle of broken ditches. Outside that was a second ditch that spiraled around. An outer ditch was mostly covered by the later Iron Age earthwork. The boser also found many pits. Curwen thought there were probably many more that weren't found.

Curwen dug trenches in each ditch he found. He also dug into six pits. In the ditches, he found chalk rubble at the bottom. He thought this was natural dirt that filled in when the site was first used. Later, in 1995, Alastair Oswald suggested it might have been filled in on purpose. Above this, there was a layer with a few pieces of Hallstatt and La Tène pottery. Curwen thought this was dirt put there by the Iron Age people to level the ground inside their new hillfort.

The next layer, above the filled-in dirt, was full of early Iron Age pottery pieces. Curwen concluded this layer was from when the Iron Age people lived there. Small pieces of flint were common in the lowest levels. Potboilers (stones heated and dropped in water to warm it) were more common in the Iron Age layers. Pieces of querns (stones used to grind grain) were also found. Large pieces were from the Iron Age, and smaller ones were from the Neolithic period.

Most of the pits found were from the Iron Age. One pit, pit 4, was shallower and only had some ox and sheep bones. It couldn't be dated. But it looked like a Neolithic pit from another site, so it might have been dug at the same time as the causewayed enclosure.

Curwen figured out what some pits were used for. Pit 1 seemed to be under a house in the late Iron Age and had trash like broken pottery. Pits 3 and 5 were also trash pits. Pit 2, in the middle of the western entrance to the hillfort, had two large postholes. It seemed to have been filled in soon after it was dug. Another pit was found in the eastern entrance. Curwen thought both pits were part of the hillfort's defense system. While digging pit 2, Curwen found a layer of flint blocks. He thought the Iron Age builders of the hillfort laid them.

Curwen also dug where the outer Neolithic ditch met the northern Iron Age rampart. Here, he found the burial of a woman, aged 25–30. Her skeleton was under a small pile of chalk. The rampart was built after she was buried. Curwen thought the burial was from the Early Bronze Age or earlier.

Animal bones found included oxen, sheep, and pigs, and a few roe deer. Sheep bones were more common in the Iron Age layers than in the Neolithic ones. Snails found in the Neolithic layers showed that the area was much wetter back then. Snails from later layers suggested it was wetter during the Bronze Age burial and hillfort building than it is now, but not as wet as in Neolithic times. Curwen estimated the Neolithic enclosure was built around 2000 BC, and the hillfort between 500 and 100 BC.

Curwen's 1930 Excavations

Curwen returned to The Trundle in 1930. This time, he dug in a more modern way. He removed soil layer by layer, which helps archaeologists understand how the site changed over time.

He opened up the inner ditch again, just south of where he dug in 1928. He also dug two more trenches in the second ditch. These new trenches didn't have the Iron Age layer found in the inner ditch. But they showed that the ditch had been dug again later, with a V-shape.

Clearing the edges around this trench revealed postholes (holes where wooden posts once stood). This made Curwen re-open two nearby areas he dug in 1928, and he found postholes there too. At first, Curwen thought the second ditch might have been "pit dwellings." But in 1954, archaeologist Stuart Piggott argued that the postholes were from the Iron Age, and Curwen agreed.

Four more pits were found and dug up. All of them contained Iron Age pottery pieces. Curwen also dug up the entire east gate area of the hillfort. He found many pits and postholes there. It was clear that not all the postholes could have been used at the same time. If they were, the gate would have been blocked! Curwen thought there must have been different gate designs over the years the hillfort was used.

He suggested that one set of holes might have been for a double gateway. Three other holes, pits 11–13, were very deep (about 7–8 feet) and square. They had ramps leading down into them. These pits had never been used; they were filled in very soon after being dug. Curwen thought the western gate might have had a similar setup. He wasn't sure what these deep holes were for. He suggested they might have been part of a grand plan for defense that was started just before the hillfort was abandoned. Large wooden gates might have used these postholes and needed iron pivot mechanisms.

Later Investigations: 1980 and 2011

In 1980, a "rescue excavation" happened at The Trundle. This type of dig happens when a site is about to be disturbed, for example, by new construction. Owen Bedwin and Frederick Aldsworth investigated a part of the spiral ditch. They found two postholes, one very new and one empty. The soil layers in the ditch matched Curwen's findings. However, Bedwin and Aldsworth also found a fourth layer of chalky lumps at the very bottom.

Snails found in each layer suggested that this ditch was first dug when the land around it was cleared. By the Iron Age, it seemed the land needed to be cleared again. This idea was later changed in 1982. It was then thought that the initial cleared area in Neolithic times might not have been much larger than the site itself. A few pieces of Iron Age pottery were found in the upper layers, and more Neolithic pottery in the lower layers.

Gathering Time Project: Radiocarbon Dating

The Trundle was part of a big project called "Gathering Time" in 2011. This project, funded by English Heritage, re-analyzed radiocarbon dates from almost 40 causewayed enclosures. Radiocarbon dating helps scientists figure out the age of ancient materials.

The project used a special type of analysis called Bayesian analysis. The authors, Alasdair Whittle, Frances Healy, and Alex Bayliss, published their findings in 2011. Some radiocarbon dates from animal bones, published in 1988, were included. Four more samples were taken from finds from the earlier digs.

Because there were not many samples, it was hard to create a very precise timeline. However, the results suggest that the inner ditch dates to after 3900–3370 BC. The second ditch dates to after 3650–3520 BC. The spiral ditch dates to after 3940–3370 BC. Overall, these results mean the Neolithic earthworks were likely built in the middle of the fourth millennium BC.

Other Discoveries and Surveys

In 1975, a skeleton was found in a shallow grave near the foot of The Trundle. The skull and some backbones were missing. It looked like the body was headless when buried. Pieces of an iron belt buckle were also found. Since there used to be a gallows (a structure for hanging criminals) on The Trundle, it's thought the body might have been someone executed there between 1000 AD and 1825 AD.

In 1987 and 1989, geophysical surveys were done at The Trundle. These surveys use special equipment to look underground without digging. This was done in the area where British Telecom wanted to build radio equipment. In 1994, a plan to redevelop a carpark led to another excavation. Four trenches were dug, and small amounts of prehistoric pottery and flints were found.

A detailed survey of the site was made in 1995. This survey covered both the hillfort and the causewayed enclosure. The report, written by Alastair Oswald, identified fifteen possible Iron Age house platforms inside the ramparts. Oswald also noted three possible Roman building platforms. Later "watching briefs" (when archaeologists watch during construction work) in 1997, 2000, 2002, and 2013 found nothing new of archaeological interest.

Protecting The Trundle Today

The Trundle was officially listed as a "scheduled monument" in 1933. This means it's a very important historical site that is protected by law. It is located within the beautiful South Downs National Park.

There are three walking trails that allow people to visit and explore the site. In 2010, The Trundle temporarily hosted a large bronze sculpture called Artemis. This was a 30-foot (9.1 m) tall sculpture of a horse by artist Nic Fiddian-Green. The sculpture was later moved to Australia in 2011.

Images for kids

-

The areas excavated by Curwen in 1928 are shown in black. P1 to P6 are the six pits investigated that year. ID, 2D, and SD stand for inner, second, and spiral ditch respectively. CI to CIV stand for cuttings I to IV. TT-1 was an extension of ID-CI. Areas in green were excavated in 1930, including pits P7 to P9.

See also

In Spanish: The Trundle para niños

In Spanish: The Trundle para niños

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |