Thích Nhất Hạnh facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Thích Nhất Hạnh |

|

|---|---|

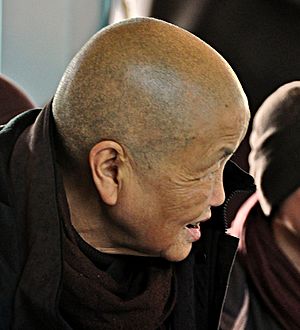

Nhất Hạnh in Paris in 2006

|

|

| Religion | Thiền Buddhism |

| School | Linji school (Lâm Tế) Order of Interbeing Plum Village Tradition |

| Lineage | 42nd generation (Lâm Tế) 8th generation (Liễu Quán) |

| Known for | Engaged Buddhism, father of the mindfulness movement |

| Other names | Nguyễn Đình Lang |

| Dharma names | Phùng Xuân, Điệu Sung |

| Personal | |

| Born | Nguyễn Xuân Bảo 11 October 1926 Huế, Thừa Thiên, Annam, French Indochina |

| Died | 22 January 2022 (aged 95) Huế, Thừa Thiên-Huế Province, Vietnam |

| Senior posting | |

| Based in | Plum Village Monastery |

| Title | Thiền Sư (Zen master) |

| Religious career | |

| Teacher | Thích Chân Thật |

Thích Nhất Hạnh (/ˈtɪk ˈnjʌt ˈhʌn/ tik nyuht huhn; Vietnamese: [tʰǐk̟ ɲə̌t hâjŋ̟ˀ]; born Nguyễn Xuân Bảo; 11 October 1926 – 22 January 2022) was a Vietnamese Buddhist monk, peace activist, writer, poet, and teacher. He started the Plum Village Tradition and is known for creating "Engaged Buddhism". Many call him the "father of mindfulness" because he helped bring Buddhist ideas to the Western world.

In the mid-1960s, Nhất Hạnh helped start the School of Youth for Social Services. He also created the Order of Interbeing. He was sent away from South Vietnam in 1966 because he spoke out against the war. In 1967, Martin Luther King Jr. even nominated him for a Nobel Peace Prize.

Nhất Hạnh founded many monasteries and centers for practice. He lived for many years at the Plum Village Monastery in southwest France, which he started in 1982. He traveled worldwide to give talks and lead retreats. He taught that "deep listening" can solve conflicts without violence. He also wanted people to understand how everything in nature is connected. He came up with the term "engaged Buddhism" in his book Vietnam: Lotus in a Sea of Fire.

After being away for 39 years, Nhất Hạnh was allowed to visit Vietnam in 2005. In 2018, he returned to his original temple, Từ Hiếu Temple, near Huế. He lived there until he passed away in 2022 at the age of 95.

Contents

Early Life of Thích Nhất Hạnh

Nhất Hạnh was born Nguyễn Xuân Bảo on October 11, 1926. This was in the old capital city of Huế in central Vietnam. His family was the Nguyễn Đình family. The famous poet Nguyễn Đình Chiểu was one of his ancestors.

His father, Nguyễn Đình Phúc, worked for the French government. His mother, Trần Thị Dĩ, was a homemaker. Nhất Hạnh was the fifth of their six children. He lived with his large family at his grandmother's house until he was five.

When he was seven or eight, he felt great joy seeing a drawing of a peaceful Buddha. On a school trip, he visited a mountain where a hermit lived. People said the hermit sat quietly to become peaceful like the Buddha. Nhất Hạnh explored the area and found a natural well. He drank from it and felt completely happy. This experience made him want to become a Buddhist monk. At age 12, he wanted to train as a monk. His parents were careful at first, but they let him follow this path when he was 16.

Names of Thích Nhất Hạnh

Nhất Hạnh had many names during his life. As a boy, his family name for school was Nguyễn Đình Lang. But people knew him by his nickname, Bé Em.

When he wanted to become a monk, he received a spiritual name, Điệu Sung. He got a Lineage name, Trừng Quang, when he officially became a lay Buddhist. When he became a monk, he received a Dharma name, Phùng Xuân. He took the Dharma title Nhất Hạnh when he moved to Saigon in 1949.

The Vietnamese name Thích comes from "Thích Ca" or "Thích Già". This means "of the Shakya clan". All Buddhist monks and nuns in East Asian Buddhism use this name as their last name. It shows that their first family is the Buddhist community.

Nhất means "one" or "best quality". Hạnh means "action" or "good nature". He translated his Dharma names as "One" (Nhất) and "Action" (Hạnh). Vietnamese names put the family name first, then a middle name, and then the given name.

His followers called him Thầy ("master" or "teacher"). They also called him Thầy Nhất Hạnh. He is also known as Thiền Sư Nhất Hạnh ("Zen Master Nhất Hạnh").

Education and Early Teachings

At 16, Nhất Hạnh joined the monastery at Từ Hiếu Temple. His main teacher was Zen Master Thanh Quý Chân Thật. He trained as a novice for three years. He learned about Vietnamese traditions of Mahayana and Theravada Buddhism. He also learned Chinese, English, and French.

Nhất Hạnh went to Báo Quốc Buddhist Academy. But he felt it didn't teach enough about philosophy, literature, or foreign languages. So, in 1950, he left and moved to the Ấn Quang Pagoda in Saigon. He became a monk there in 1951. He sold books and poetry to support himself while studying science at Saigon University.

In 1955, Nhất Hạnh went back to Huế. He worked as the editor of Phật Giáo Việt Nam (Vietnamese Buddhism). This was the official magazine for Vietnamese Buddhists. He did this for two years until his writing was stopped. Higher-ranking monks did not like his ideas. He thought it was because he wanted different Buddhist groups in South Vietnam to unite.

In 1956, while he was teaching in Đà Lạt, his name was removed from Ấn Quang's records. This meant the temple no longer recognized him. In late 1957, Nhất Hạnh decided to go on a retreat. He started a small monastic group called Phương Bôi in Đại Lao Forest near Đà Lạt. During this time, he taught at a local high school and kept writing. He promoted the idea of a kind, unified Buddhism.

From 1959 to 1961, Nhất Hạnh taught short courses on Buddhism in Saigon. One class at the large Xá Lợi Pagoda was canceled because his teachings were not approved. Facing more problems from religious and government leaders, Nhất Hạnh accepted a scholarship in 1960. He went to Princeton University to study different religions. He also taught at Columbia University and Cornell University. By then, he spoke French, Classical Chinese, Sanskrit, Pali, and English, besides his native Vietnamese.

Activism and Peace Efforts

Working for Peace in Vietnam (1963–1966)

In 1963, after the government changed in South Vietnam, Nhất Hạnh returned home. He came back on December 16, 1963, because Thich Tri Quang asked for his help. Thich Tri Quang was a monk who protested against unfair treatment of Buddhists.

In January 1964, different Buddhist groups joined to form the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam (UBCV). Nhất Hạnh suggested that the UBCV publicly ask for the Vietnam War to end. He also wanted them to create a place to train future Buddhist leaders and social workers.

In 1964, two of Nhất Hạnh's students started La Boi Press. They published 12 books in two years. But by 1966, the publishers risked arrest because the word "peace" was seen as supporting communism. Nhất Hạnh also edited Hải Triều Âm (Sound of the Rising Tide), the UBCV's official magazine. He always spoke for peace. He even called the Viet Cong "brothers" in September 1964. The South Vietnamese government then closed the magazine.

On May 1, 1966, at Từ Hiếu Temple, Nhất Hạnh became a dharmacharya (teacher). This made him the spiritual head of Từ Hiếu and other monasteries.

Vạn Hanh Buddhist University

On March 13, 1964, Nhất Hạnh and monks at An Quang Pagoda started the Institute of Higher Buddhist Studies. This became Vạn Hanh Buddhist University in Saigon. It was a private school that taught Buddhist studies, Vietnamese culture, and languages. Nhất Hạnh taught Buddhist psychology there. He also helped raise money for the university.

School of Youth for Social Service (SYSS)

In 1964, Nhất Hạnh helped create the School of Youth for Social Service (SYSS). This was a group of Buddhist peace workers. They went to villages to build schools, health clinics, and help rebuild after the war. The SYSS had 10,000 volunteers. They helped war-torn villages and set up medical centers.

Nhất Hạnh left for the U.S. shortly after and was not allowed to return. Sister Chân Không took charge of the SYSS. She was very important in starting and running the SYSS. The SYSS continued its relief work without taking sides in the war.

The Order of Interbeing

Nhất Hạnh started the Order of Interbeing (Vietnamese: Tiếp Hiện) between 1964 and 1966. This group included monks, nuns, and lay people. He taught them the Five Mindfulness Trainings and the Fourteen Mindfulness Trainings. The Order of Interbeing grew into a worldwide community. They focused on "mindfulness practice, ethical behavior, and compassionate action." By 2017, thousands of people were part of this group.

During the Vietnam War

Nhất Hạnh returned to the U.S. in 1966 to lead a meeting at Cornell University. He continued his work for peace. He was invited to speak about U.S. policy in Vietnam. On June 1, he shared a five-point plan for the U.S. government. He asked the U.S. to state its wish to help Vietnam, stop air strikes, and show it was willing to leave. He also asked for help with rebuilding. In 1967, he wrote Vietnam — The Lotus in the Sea of Fire about his ideas. The South Vietnamese government then called him a traitor and a communist.

While in the U.S., Nhất Hạnh visited Gethsemani Abbey. He spoke with the Trappist monk Thomas Merton. When the South Vietnamese government threatened to stop Nhất Hạnh from returning, Merton wrote an essay supporting him. In 1964, after his poem "whoever is listening, be my witness: I cannot accept this war..." was published, Nhất Hạnh was called an "antiwar poet" by the American press.

In 1965, he wrote a letter to Martin Luther King Jr. called "In Search of the Enemy of Man". During his 1966 visit to the U.S., Nhất Hạnh met King. He urged King to speak out against the Vietnam War. In 1967, King gave a speech called "Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence". This was his first public speech questioning U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Later that year, King nominated Nhất Hạnh for the 1967 Nobel Peace Prize. King said, "I do not personally know of anyone more worthy of the Nobel Peace Prize than this gentle monk from Vietnam." He also called Nhất Hạnh "an apostle of peace and non-violence". The prize committee did not give an award that year.

Living in France

Nhất Hạnh moved to Paris in 1966. He became the head of the Vietnamese Buddhist Peace Delegation.

In 1969, Nhất Hạnh started the Unified Buddhist Church in France. In 1975, he created the Sweet Potatoes Meditation Centre. For the next seven years, he focused on writing. He completed The Miracle of Mindfulness, The Moon Bamboo, and The Sun My Heart.

Nhất Hạnh began teaching mindfulness in the mid-1970s. His books, especially The Miracle of Mindfulness (1975), were important for his early teachings. He said he wrote The Miracle of Mindfulness for social workers in Vietnam. They faced danger every day. He wanted to help them continue their work. Later, many people in the West found it helpful, so it was translated into English.

Helping Boat People and Leaving Singapore

When the North Vietnamese army took control in 1975, Nhất Hạnh was not allowed to return to Vietnam. The government also banned his books. He then started helping Vietnamese boat people in the Gulf of Siam. He eventually stopped due to pressure from the governments of Thailand and Singapore.

He stayed in Singapore to organize a secret rescue. With help from people in France, the Netherlands, and other European countries, he hired a boat. They brought food, water, and medicine to refugees at sea. Fishermen who rescued boat people would call his team. They would take the refugees to the French embassy at night. They helped them get inside the embassy grounds. In the morning, embassy staff would find them and hand them over to the police. This put them in safer detention.

When the Singapore government found out about this, the police surrounded his office. They took the passports of Nhất Hạnh and Chân Không. They were given 24 hours to leave the country. Only with help from the French ambassador were they given 10 days to finish their rescue work.

Nhất Hạnh was only allowed to return to Singapore in 2010. He led a meditation retreat there.

Plum Village Monastery

In 1982, Nhất Hạnh and Chân Không started the Plum Village Monastery. This is a vihara (Buddhist monastery) in the Dordogne area of southern France. Plum Village is the largest Buddhist monastery in Europe and America. It has over 200 monks and nuns and more than 10,000 visitors each year.

The Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism is the official group that runs Plum Village in France.

More Practice Centers

By 2019, Nhất Hạnh had built many monasteries and retreat centers. These were in countries like France, the U.S., Australia, Thailand, Vietnam, and Hong Kong. Other centers he started in the U.S. include Blue Cliff Monastery in Pine Bush, New York. Also, Deer Park Monastery in Escondido, California, and Magnolia Grove Monastery in Batesville, Mississippi. He also started the European Institute of Applied Buddhism in Waldbröl, Germany.

These monasteries are open to the public for much of the year. They offer retreats for everyday people. The Order of Interbeing also holds retreats for specific groups. These include families, teenagers, military veterans, and people of color.

According to the Thích Nhất Hạnh Foundation, Nhất Hạnh's monastic order had over 750 monks and nuns in 9 monasteries worldwide by 2017.

Nhất Hạnh also started two monasteries in Vietnam. One was at the original Từ Hiếu Temple near Huế. The other was at Prajna Temple in the central highlands.

Writings and Books

Nhất Hạnh published over 130 books. More than 100 of these are in English. By January 2019, his books had sold over five million copies worldwide. His books cover many topics. These include spiritual guides, Buddhist texts, mindfulness teachings, poetry, and scholarly essays on Zen practice. His books have been translated into more than 40 languages. In 1986, Nhất Hạnh founded Parallax Press. This is a nonprofit book publisher and part of the Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism.

During his long time away from Vietnam, Nhất Hạnh's books were often secretly brought into the country. They had been banned there.

Later Activism

In 2014, important leaders from Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, Anglican, Catholic, and Orthodox Christian faiths met. They signed a promise against modern-day slavery. The promise called for slavery to end by 2020. Nhất Hạnh was represented by Chân Không at this meeting.

Nhất Hạnh was known for not eating animal products. He believed this was a way to be nonviolent towards animals.

Christiana Figueres, a leader in climate change efforts, said Nhất Hạnh helped her. He taught her "deep listening" and empathy. This helped her work on the Paris Agreement on climate change.

Relations with Vietnamese Governments

Nhất Hạnh's relationship with the government of Vietnam changed over the years. He stayed away from politics. But he did not support the South Vietnamese government's policies that favored Catholics. He questioned America's involvement in the war. This put him at odds with the Saigon leaders. They banned him from returning to South Vietnam in 1966.

His relationship with the communist government in Vietnam was difficult. This was because of their atheism, though he was not very interested in politics. The communist government was unsure about him. They did not trust his work with Vietnamese people living outside the country. They also stopped his prayer ceremonies several times.

Return Visits to Vietnam (2005–2007)

In 2005, after long talks, the Vietnamese government allowed Nhất Hạnh to visit. He was also allowed to teach there. Four of his books were published in Vietnamese. He traveled the country with monks, nuns, and lay members of his Order. This included a return to his original temple, Tu Hieu Temple in Huế. Nhất Hạnh arrived on January 12, after 39 years away.

Despite some disagreements, Nhất Hạnh returned to Vietnam in 2007. The heads of the banned UBCV, Thich Huyen Quang and Thich Quang Do, were still under house arrest. Some people from the UBCV felt his visit was a betrayal. They thought it showed he was willing to work with those who treated his fellow Buddhists unfairly. A UBCV spokesperson said, "I believe Thích Nhất Hạnh's trip is used by the Hanoi government to hide its repression of the Unified Buddhist Church."

The Plum Village website listed three goals for his 2007 trip. These were to support new monks and nuns in his Order. Also, to hold "Great Chanting Ceremonies" to help heal war wounds. And to lead retreats for monastics and laypeople. The chanting ceremonies were first called "Grand Requiem for Praying Equally for All to Untie the Knots of Unjust Suffering." But Vietnamese officials objected. They said it was not acceptable to "equally" pray for South Vietnamese and U.S. soldiers. Nhất Hạnh agreed to change the name to "Grand Requiem For Praying." During the 2007 visit, Nhất Hạnh suggested to President Nguyen Minh Triet that the government should not control religion. A police officer later said Nhất Hạnh broke Vietnamese law by doing this. The officer said, "[Nhất Hạnh] should focus on Buddhism and keep out of politics."

In 2005, followers of Nhất Hạnh were invited to use Bat Nha monastery. They were invited by Abbot Duc Nghi, a member of the official Buddhist Sangha of Vietnam. Nhất Hạnh's followers say that in 2006, Nghi agreed to let them use Bat Nha. Nhất Hạnh's followers spent $1 million to improve the monastery. They built a meditation hall for 1,800 people. Some believe the government's initial support was to improve its image for religious freedom. This could help Vietnam join the World Trade Organization and get more foreign investment.

In 2008, Nhất Hạnh made some statements about the Dalai Lama in an Italian TV interview. His followers say this upset Chinese officials. They then put pressure on the Vietnamese government. The chairman of Vietnam's religious committee sent a letter. It accused Nhất Hạnh's group of publishing false information about Vietnam. It said the information made Vietnam's religious policies look bad and could harm national unity. The chairman asked Nhất Hạnh's followers to leave Bat Nha. The letter also said Abbot Duc Nghi wanted them to leave. "Duc Nghi is breaking a promise he made to us," said Brother Phap Kham. "We have videos of him inviting us to make the monastery a place for Plum Village worship, even after he dies." In September and October 2009, there was a conflict. It ended when authorities cut power. Then police raids happened, helped by groups of people. The attackers used sticks and hammers. They dragged out hundreds of monks and nuns. "Senior monks were dragged like animals," a villager said. Two senior monks had their IDs taken and were put under house arrest without charges.

Religious Approach and Influence

Nhất Hạnh combined different Buddhist teachings. These included ideas from early Buddhist schools, Mahayana traditions like Yogācāra and Zen. He also used ideas from Western psychology. He taught mindfulness of breathing and the four foundations of mindfulness. He offered a modern way to practice meditation. His idea of "interbeing" for the Prajnaparamita comes from the Huayan school of thought. This school is often seen as a basis for Zen.

In September 2014, Nhất Hạnh finished new English and Vietnamese translations of the Heart Sutra. He wrote to his students that he made these new translations because he thought some words in the original text caused misunderstandings for almost 2,000 years.

Nhất Hạnh was also a leader in the Engaged Buddhism movement. He is credited with creating the term. He encouraged people to actively work for change. He rewrote the five precepts for lay Buddhists. These rules traditionally said what not to do. Nhất Hạnh changed them to focus on taking positive action. For example, instead of just not stealing, he wrote: "prevent others from profiting from human suffering." This means taking action against unfair practices. He said the 13th-century Vietnamese Emperor Trần Nhân Tông first had this idea. Trần Nhân Tông gave up his throne to become a monk. He founded the Vietnamese Buddhist school of the Bamboo Forest tradition.

Called "the Father of Mindfulness," Nhất Hạnh is known for bringing Buddhism to the West. He especially made mindfulness popular. James Shaheen, editor of Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, said, "In the West, he's an icon." His 1975 book The Miracle of Mindfulness helped set the stage for using mindfulness to treat depression. This influenced the work of Marsha M. Linehan, who created dialectical behavior therapy (DBT).

J. Mark G. Williams of Oxford University said Nhất Hạnh could share the main ideas of Buddhist wisdom. He made it easy for people worldwide to understand. He built a bridge between modern psychology and ancient wisdom practices. One of Nhất Hạnh's students, Jon Kabat-Zinn, created the mindfulness-based stress reduction course. This course is now used in hospitals and medical centers around the world. By 2015, about 80% of medical schools offered mindfulness training. By 2019, mindfulness, as taught by Nhất Hạnh, was the basis for a $1.1 billion industry in the U.S.

Nhất Hạnh was also known for talking with people from different religions. This was not common when he started. He was friends with Martin Luther King Jr. and Thomas Merton. King wrote in his Nobel nomination for Nhất Hạnh: "His ideas for peace, if applied, would build a monument to ecumenism, to world brotherhood, to humanity." Merton wrote an essay called "Nhất Hạnh Is My Brother." He said, "I have far more in common with Nhất Hạnh than I have with many Americans." He also said it was important to admit these connections.

The same year, Nhất Hạnh met with Pope Paul VI. They both asked Catholics and Buddhists to help bring about world peace. This was especially for the conflict in Vietnam. According to Buddhism scholar Sallie B. King, Nhất Hạnh was very good at explaining teachings in a way that felt universal. He used language that was not just Buddhist. He saw these same basic values in other religions too.

Final Years and Passing

In November 2014, Nhất Hạnh had a severe brain hemorrhage. He was hospitalized. After months of recovery, he was released from the clinic. In July 2015, he flew to San Francisco for more intense therapy. He returned to France in January 2016. After spending 2016 in France, Nhất Hạnh traveled to Thai Plum Village. He continued to see specialists but could not speak for the rest of his life.

In November 2018, the Plum Village community announced that Nhất Hạnh, then 92, had returned to Vietnam for his final days. He would live at Từ Hiếu Temple. He had shown through gestures that he wanted to return to Vietnam.

Even though Nhất Hạnh could no longer speak, Vietnamese authorities assigned plainclothes police to watch him at the temple.

Death

Nhất Hạnh passed away at his home in Từ Hiếu Temple on January 22, 2022. He was 95 years old. His death was due to problems from his stroke seven years earlier. Many Buddhist groups in and outside Vietnam mourned his death. The Dalai Lama, South Korean President Moon Jae-in, and the U.S. State Department all sent their condolences.

His funeral lasted five days. There was a seven-day wake, ending with his cremation on January 29.

After a 49-day mourning period, Nhất Hạnh's ashes were divided. They were scattered in Từ Hiếu Temple and other temples connected to Plum Village.

Awards and Honours

Nobel laureate Martin Luther King Jr. nominated Nhất Hạnh for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1967. The prize was not given that year. Nhất Hạnh received the Courage of Conscience award in 1991.

Nhất Hạnh received the 2015 Pacem in Terris Peace and Freedom Award.

In November 2017, the Education University of Hong Kong gave Nhất Hạnh an honorary doctorate. This was for his "lifelong contributions to the promotion of mindfulness, peace and happiness across the world." He could not attend the ceremony in Hong Kong. So, a small ceremony was held on August 29, 2017, in Thailand. There, a university vice-president presented the award to Nhất Hạnh.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Thích Nhất Hạnh para niños

In Spanish: Thích Nhất Hạnh para niños

- Buddhism in Vietnam

- Buddhist crisis

- Vietnamese Thiền

- List of peace activists

- Religion and peacebuilding