Three Brothers (jewel) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids The Three Brothers |

|

|---|---|

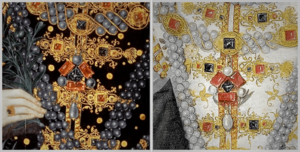

A small painting of the Three Brothers, made for the city of Basel around 1500

|

|

| Material | Spinels, pearls, diamond, gold |

| Weight | ~300 carats (60 g) total |

| Created | 1389 |

| Place | Paris, France |

| Present location | Unknown since 1645 |

The Three Brothers (also known as the Three Brethren) was a very special piece of jewelry made in the late 1300s. It had three rectangular red spinels (a type of gemstone) placed around a sparkling diamond in the middle. This jewel became famous because many important historical figures owned it.

First, it was ordered by Duke John the Fearless of Burgundy. It stayed with the Burgundian royal family for almost 100 years. Then, it was bought by a rich German banker named Jakob Fugger. Later, the Three Brothers were sold to Edward VI and became part of the Crown Jewels of England. This was from 1551 to 1643. Queen Elizabeth I and King James VI and I often wore it. In the 1640s, Henrietta Maria, who was married to King Charles I, tried to sell the jewel to get money for the English Civil War. But we don't know if she succeeded. No one knows where the Three Brothers jewel has been since 1645.

Contents

What the Jewel Looked Like

The Three Brothers jewel stayed mostly the same for over 250 years. It was changed a little bit in 1623, but its main look and the gems in it stayed the same. It was first made to be worn as a clasp on a shoulder or as a pendant.

The jewel had:

- Three rectangular red spinels, each weighing about 70 carats. Back then, these were called "balas rubies."

- Three round white pearls (about 10–12 carats each) placed between the spinels.

- Another large pearl (18–20 carats) hanging from the bottom spinel.

- In the very center, there was a deep blue diamond weighing about 30 carats. It was shaped like a pyramid or an octahedron. Since diamond cutting wasn't common before 1400, the jeweler likely just squared off its natural shape.

The jewel was about 8.7 by 6.9 centimeters (3.4 by 2.7 inches) in its original form.

When the jewel was first listed in a record in 1419, it was described like this:

A very fine and rich buckle, with a very big pointed diamond in the middle. Around it are three fine square balas stones called the three brothers, and three sizable fine pearls in between them. Under this buckle hangs a very large fine pearl shaped like a pear.

In 1587, when the Three Brothers were given to Queen Elizabeth I's helper, Mary Radcliffe, it was described again:

A beautiful golden flower with three great balas stones in the middle, a great pointed diamond, and three great pearls fixed with a beautiful hanging pearl, called the Brethren.

The Jewel's Early Journey

The Three Brothers jewel was ordered by Duke John the Fearless of Burgundy in the late 1380s. It was one of the most valuable treasures of the Burgundian royal family. A goldsmith from Paris named Herman Ruissel created it in 1389. Records show the jewel was sold on October 11 and November 24 of that year.

Duke John once pawned (borrowed money using it as security) the jewel in 1412, but he got it back before 1419. When the Duke was killed in 1419, the Three Brothers jewel was passed down to his son, Philip the Good.

The jewel stayed in Burgundy during Philip's rule. When he died in 1467, his son, Charles the Bold, inherited it. Charles had one of the strongest armies of his time. He would take many valuable items with him to battles, believing they would bring him luck. These items included the Three Brothers jewel.

In 1476, Charles fought against the Old Swiss Confederacy in the Burgundian Wars. He suffered a terrible defeat at the Battle of Grandson. Charles had to escape quickly, leaving behind his army's equipment and many treasures, including the Three Brothers. The Swiss army looted his tent and took the jewel.

The pendant was sold to the leaders of the city of Basel in Switzerland. They had an expert from Venice check its value. The city also ordered a small painting of the jewel, exactly its real size, to help them sell it later. This painting is the earliest picture we have of the Three Brothers. It is now in the Basel Historical Museum. The jewel was hidden for a few years because the leaders of Basel were afraid that the House of Habsburg, who took over the Duchy of Burgundy, would try to get back items they believed were stolen from Charles. Finally, in 1502, the jewel was put up for sale.

In 1504, Basel successfully sold the Three Brothers to Augsburg banker Jakob Fugger after a year of talks. Fugger was a very rich merchant who traded in cloth and metals. He also lent money to the Habsburg royal family. The sale to Fugger included the Brothers and three other jewels from Charles's collection. The total price was 40,200 florins, which was a huge amount of money back then. For Fugger, jewels and precious stones were like money he could easily use or sell for a profit. He even hoped to sell the Brothers to Emperor Maximilian I, but the Emperor thought Fugger's price was too high.

The jewel stayed with the Fuggers for several decades. In the 1540s, Jakob Fugger's nephew, Anton Fugger, who was now running the family business, decided to sell some of the family's treasures. He first tried to sell the Brothers to King Ferdinand I and Emperor Charles V, but they didn't buy it. He even refused an offer from the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent because he didn't want the jewel to go to a non-Christian ruler.

When European Christian kings didn't buy the jewel, the Fuggers turned to King Henry VIII of England. Henry loved jewels and spent a lot of money on them. Talks to sell the jewel to Henry started as early as 1544, but they continued until Henry died in 1547. The deal was finally completed in May 1551, under Henry's 14-year-old son, Edward VI. King Edward wrote in his diary that he had to buy the jewel from "Anthony Fulker" (Anton Fugger) for 100,000 crowns. This was because the English monarchy owed the Fuggers' bank a lot of money. After this, the Three Brothers became part of the Crown Jewels of England.

As an English Crown Jewel

King Edward left the pendant with his chief financial officer, William Paulet, for safekeeping. When Edward died after six years as king, his half-sister Mary inherited the Brothers jewel when she became Queen in July 1553. A list of items given to Mary in 1553 described the jewel. This description showed that it had changed very little since Duke John the Fearless first ordered it more than 150 years earlier. Mary died in 1558 after ruling for only five years.

The jewel appeared again during the reign of her sister, Elizabeth I. Like her father, Henry VIII, Elizabeth knew how to show off her wealth. She clearly liked the bright red and white jewel with its unusual triangular shape. The Queen wore it as part of her crown jewels on several occasions. It is shown clearly in at least two of her portraits.

One portrait is the Ermine Portrait (around 1585), where the Brothers jewel hangs from a large, pearl-covered necklace against a black dress. The other is the less known Elizabeth I of England holding an olive branch (around 1587). In this painting, the pendant is the only important piece of jewelry she wears, set against a richly decorated white dress. Elizabeth died in 1603 after ruling for 45 years. By then, the jewel was so connected to her that when a marble monument was built for her in Westminster Abbey in 1606, a copy of the Brothers jewel was placed on her tomb statue.

When Elizabeth died, the jewel went to her successor, James I. He had been King of Scotland as James VI before becoming King of England. In 1606, the Three Brothers was listed as a jewel that should "never be taken from the Crown." The pendant was a favorite of James, who had it changed into a hat jewel. A portrait of James from around 1605 shows the Brothers jewel in great detail on his black hat, along with a pearl-studded band.

Near the end of James's rule, the jewel was reset, possibly for the first time since it was made. In 1623, James's son and future king, Charles, went on a secret trip to Spain. He wanted to arrange a marriage between himself and the Spanish princess, Maria Anna of Spain. Very expensive jewelry was taken on the trip to impress the Spanish king. The royal jeweler worked day and night to reset the chosen jewels. James wrote to Charles that he would send him "the Three Brethren that you knowe full well, but newlie sette."

Later History and Disappearance

The marriage plan with Spain didn't work out. James died in March 1625, and the new King Charles I instead married the French princess Henrietta Maria. The jewel was given to royal helpers to keep safe in November 1625.

King Charles often argued with the Parliament of England. One reason was his belief that kings had a "divine right" to rule, which made him think the crown jewels were his personal property. Charles had money problems. He had already pawned the Brothers jewel in the Netherlands in 1626, only getting it back in 1639. When the monarchy was almost bankrupt in 1640, Charles sent Henrietta to Europe to sell what she could of the crown jewels.

Henrietta arrived in The Hague in March 1642. Parliament protested, saying she had taken "Treasure, in Jewels, Plate, and ready Money" that would "impoverish the State" and cause trouble in Britain. However, Henrietta found that buyers were not eager to buy important pieces like the Three Brothers. She wrote to her husband: "The money is not ready, for on your jewels, they will lend nothing. I am forced to pledge all my little ones." By June, it was reported to Parliament that the Brothers jewel was still unsold.

The trail of the jewel began to disappear at the end of Henrietta's trip in 1643. There are no records of her selling or pawning the pendant in the Netherlands. It is likely that the Brothers returned with her to England. As England fell into the First English Civil War between Charles and Parliament, Henrietta fled to Paris in 1644. There, she immediately tried to raise money again. The local market still showed little interest. But in early 1645, she managed to sell an unnamed piece of jewelry for a relatively low price. This piece was described in a way that closely matched the original description of the Three Brothers, if it had been changed by adding smaller diamonds. However, there is no definite proof that it was the same item.

The fate of the Brothers jewel after 1645 is unknown. Some people think the jewel was broken apart. Others believe it was bought by the French chief minister, Cardinal Mazarin, who was a famous jewel collector and to whom Henrietta Maria owed a lot of money. There has also been talk that the pendant was changed, possibly creating a jewel called the Three Sisters. The Sisters were offered for sale around the time Henrietta sold her unnamed jewel in 1645. But besides the similar name, there is no strong proof that the Brothers became the Sisters. No one has seen the Three Brothers jewel for sure since then.

In Books

Tobias Hill wrote a novel called The Love of Stones in 2001. This book tells the stories of real and made-up people who come into contact with the Three Brothers jewel.

See also

- Beau Sancy diamond—another jewel pawned through Thomas Cletcher

- Florentine Diamond—a lost jewel also thought to have once belonged to Charles the Bold

- List of diamonds

- List of missing treasures

Images for kids

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |