Tilbury Fort facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Tilbury Fort |

|

|---|---|

| Tilbury, Essex | |

Aerial view of Tilbury fort

|

|

| Coordinates | 51°27′10″N 0°22′29″E / 51.45278°N 0.37472°E |

| Type | Artillery fort |

| Site information | |

| Owner | English Heritage |

| Open to the public |

Yes |

| Condition | Intact |

Tilbury Fort is an old artillery fort located on the north bank of the River Thames in England. It was built to protect London from attacks coming from the sea. The first version of the fort was a small building with guns, put there by King Henry VIII in the 1500s. He wanted to defend England from France.

The fort was made stronger during the time of the Spanish Armada in 1588. It was also used by Parliamentary forces during the English Civil War in the 1640s to help keep London safe. After some naval attacks by the Dutch, the fort was made much bigger by Sir Bernard de Gomme starting in 1670. It became a star-shaped fort with strong walls, moats filled with water, and many guns facing the river.

Over time, Tilbury Fort was also used to store gunpowder and as a place for soldiers to stop before moving on. New gun batteries were added during the Napoleonic Wars. As military technology changed, the fort became less important for defence. By the end of the 1800s, it was mainly used as a storage and transport hub, especially during the First World War. It had a smaller role in the Second World War and stopped being a military site in 1950.

Today, English Heritage looks after Tilbury Fort as a place for visitors. Many of the newer military parts were removed in the 1950s, and the fort was restored in the 1970s. It opened to the public in 1983. The 17th-century defences are considered some of the best remaining in Britain. The fort also has the only surviving gunpowder magazines from the early 1700s in Britain.

Contents

History of Tilbury Fort

Why Was Tilbury Fort Built?

The first permanent fort at Tilbury in Essex was built because of problems between England, France, and the Holy Roman Empire. This happened during the last years of King Henry VIII's rule. Before this, local lords usually handled coastal defences.

In 1533, King Henry VIII broke away from the Pope. This made the Holy Roman Emperor, whose aunt was Henry's wife, very angry. France and the Empire then became allies against England in 1538. It looked like England might be invaded. So, in 1539, Henry ordered new forts to be built along the English coast. This plan was called the "Device programme."

The River Thames was very important. London and the royal shipyards at Deptford and Woolwich could be attacked by ships sailing up the river. The Thames estuary was a major route for trade. Tilbury was a key spot because the river narrowed there. It was also the first place invaders could easily land, as the muddy banks before it made landing hard.

Early Defences: The 1500s

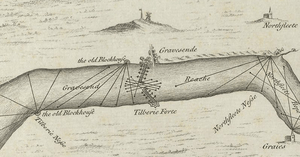

As part of King Henry's plan, the Thames was protected by several blockhouses. These were at Gravesend, Milton, and Higham on the south side of the river. On the opposite bank were West and East Tilbury. The West Tilbury Blockhouse was first called the "Thermitage Bulwark." It was built on the site of an old religious retreat.

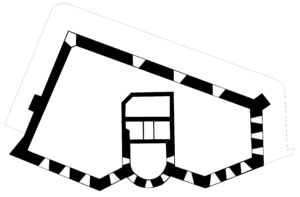

This blockhouse was designed to be D-shaped, with two levels for guns. It likely had more gun platforms along the river. The site was protected by a wall and a ditch. It had a small group of soldiers and gunners.

The threat of invasion passed, and in 1553, the guns were removed from the blockhouses. However, in the summer of 1588, there was a new threat from the Spanish Armada. An army was gathered to protect the Thames. The fortifications at Tilbury Blockhouse were quickly improved. Queen Elizabeth I visited the fort on August 8, 1588. She rode to the nearby army camp and gave a famous speech to her soldiers. Even after the Armada was defeated, fears of invasion continued. An Italian engineer, Federigo Giambelli, added more earth walls and ditches to the blockhouse. A large chain, called a boom, was even stretched across the river to Gravesend.

Changes in the 1600s

In the early 1600s, England was peaceful, so the coastal forts were not well maintained. Surveys showed problems like flooding at Tilbury Fort. In 1642, the English Civil War began. Tilbury was controlled by Parliament. They used the fort to check ships entering London and look for spies. The fort did not see any fighting during this war.

After King Charles II became king in 1660, he started a big project to improve coastal defences. In June 1667, the Dutch fleet attacked up the Thames. They were stopped from going further because they feared the forts at Tilbury and Gravesend. In truth, the forts were not ready for an attack. At Tilbury, only two guns were ready. The Dutch then attacked the English fleet at Medway. This gave the government time to improve the Thames defences.

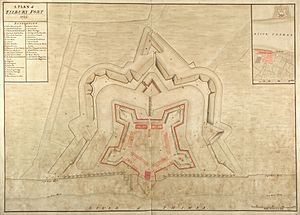

After this conflict, King Charles II asked his Chief Engineer, Sir Bernard de Gomme, to make Tilbury Fort even stronger. De Gomme drew up plans in 1665, and new designs were approved in 1670. Work began that same year and finished in 1685. Many skilled workers and forced laborers were used. About 3,000 wooden piles were brought from Norway to support the foundations in the marshy ground. The project was very expensive.

The new fort was large and star-shaped, with five sides and four strong corners called bastions. It had brick walls and two moats. Two new gatehouses protected the entrance from the north. Two lines of guns faced the river. The old blockhouse from Henry VIII's time was included, but the Elizabethan earthworks were removed. The inside of the fort was raised to prevent flooding. Barracks and other buildings were built inside.

Tilbury Fort in the 1700s and 1800s

By the early 1700s, Tilbury Fort was one of Britain's most powerful forts. The number of guns changed over time. In 1716, there were 161 guns in total, but many were old and broken.

Besides protecting the Thames, the fort had other military uses. From 1716, it became a gunpowder depot. It was safer to store gunpowder here than in London. Two large magazines were built, each holding 3,600 barrels of powder. The fort could eventually hold over 19,000 barrels. It was also used as a place for soldiers to stay. After the Jacobite rising of 1745, it even held 268 Highlander prisoners of war.

Living conditions at the fort were not good. It was surrounded by marshes, and the roads were poor. Soldiers had to drink collected rainwater. New barracks were built in 1772, but officers often preferred to live in Gravesend across the river.

During the American Revolutionary War, people worried about a French attack on London. In 1780, the army practiced an attack on the fort with 5,000 soldiers. However, there were fewer than 60 guns left at the fort, and many were in bad shape. Because of this, a new battery of guns was built in the south-east corner. Another new fort, New Tavern Fort, was built along the river to the east. Fears continued during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. Tilbury remained important for controlling the river crossing. The guns were updated, and local volunteers helped to man the forts.

In the 1800s, the fort could hold 15 officers and 150 soldiers. Living conditions remained poor, with four men sharing small rooms. In 1877, piped water was finally brought to the site.

By the 1850s, new steamships could sail up the Thames much faster. New guns and armour on warships meant they could fire on forts from further away. Because of fears of an invasion by Napoleon III of France, a special group was set up in 1859 to study Britain's defences. They suggested building new, stronger forts further down the Thames. Tilbury Fort would become a second line of defence.

Work began in 1868 to strengthen Tilbury. Heavier guns were added to fire upstream and support the new forts. The old Tudor blockhouse was destroyed to make way for these new guns. However, military technology kept improving. By the end of the 1800s, Tilbury Fort's design was old-fashioned. It was no longer needed as a main defence, but it was still used as a strategic storage place. From 1889, it became a centre to gather troops and supplies in case of an invasion.

Tilbury Fort in the 1900s and 2000s

In the early 1900s, there were new worries about attacks from fast torpedo boats and armoured ships. In 1903, four quick-firing guns were placed on Tilbury's south-east wall. Two larger guns were added in 1904. However, in 1905, the government decided that the Royal Navy and the forts further down the Thames were enough protection. All the artillery was removed, leaving only machine-guns.

Tilbury continued to be a storage centre. During the First World War, it housed up to 300 soldiers passing through. It also supplied new army camps nearby. The fort stored ammunition, and a depot for horses was built next to it. A temporary bridge was built across the Thames for moving troops. Anti-aircraft guns and searchlights were placed at the fort after air raids in 1915. They helped shoot down a German Navy Zeppelin, L15.

Between the two World Wars, the government thought the fort was no longer useful for military purposes. They tried to sell it, but it didn't happen. During the Second World War, the fort first held a control room for anti-aircraft operations. Trenches were dug around the area to stop air attacks. Some buildings, including the soldiers' barracks, were bombed and damaged. They were torn down after the war.

Tilbury Fort stopped being a military site relatively early after the war. In 1950, the Ministry of Works took over the site. Restoration work happened in the 1970s, including building replica wooden bridges. It opened to the public in 1982.

Today, English Heritage manages the fort as a tourist attraction. It is protected under UK law as a scheduled monument. The officers' barracks is a special listed building.

Tilbury Fort's Design

Tilbury Fort looks much like it did after Sir Bernard de Gomme rebuilt it in the late 1600s. It has some additions from the 1800s. Its design is mostly Dutch, with layers of outer and inner defences. These were meant to let the fort attack enemy ships while being safe from land attacks. Historic England calls it "England's most spectacular" example of a late 17th-century fort.

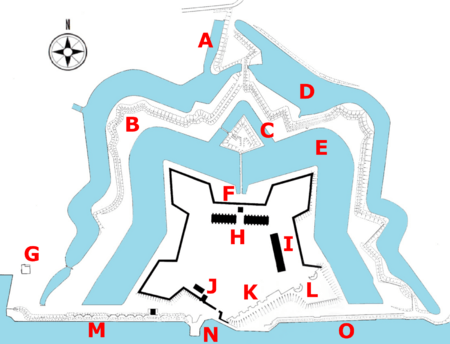

Outer Defences and Moats

The outer defences include two moats filled with water from the Thames. These moats are separated by a ring of defensive walls. The inner moat is about 50 metres (164 feet) wide. The fort is entered from the north through a triangular defence called a redan. A raised path connects the redan to the outer defences. These outer defences have a complex pattern of walls and a hidden pathway. There are strong corners (bastions) on the north-west and north-east. Two triangular points, which once held cannons, stick out from the west and east sides.

A replica wooden bridge crosses the water from the outer defences to an island called a ravelin. Another replica bridge, with two drawbridges, connects the ravelin to the inner defences. The ravelin helped block enemy cannon fire aimed at the fort's entrance. It could also fire at enemies who broke through the outer defence line.

On the south side, facing the river, are the West and East Lines of gun positions. These were built in the 1700s. Most of the original gun positions on the West Line remain, but only one on the East Line has survived. Between these lines is a quay, used for bringing supplies from the Thames. You can still see parts of the narrow railway tracks from the First World War. A sluice gate in the south-west corner controlled the water in the moats. It allowed them to be drained if they froze in winter, which would make it easier for attackers.

Inner Defences and Buildings

The inner defences are mostly five-sided, with four strong bastions around a central parade ground. From the south, you enter the fort through the Water Gate. This two-story gatehouse is from the late 1600s. It has a grand stone front with carvings of old weapons. The empty space at the front probably once held a statue of King Charles II. This building was originally the home of the master gunner.

Most of the fort's inside is taken up by the parade ground, which is about 2.5 acres (1 hectare) in size. The parade ground was raised in the 1600s and 1800s using chalk and dirt. By the early 1900s, it had four large warehouses, which are now gone.

East of the Water Gate, the south-eastern defences and bastion were rebuilt in the early 1900s. They held positions for four quick-firing guns and two larger guns. Tunnels led to an underground magazine. Four old artillery pieces, from 1898 to 1942, are on display. Facing the parade ground are the officers' quarters, a row of houses likely from the late 1700s. There is also a stables at the north end. The north-east bastion was changed after 1868 and has an earth-covered magazine. It also has positions for large rifled guns.

On the north side of the parade ground are two magazines from the early 1700s. These were specially designed without iron, to avoid sparks that could cause an explosion. They were built using wood and copper. They are the only examples of their kind left in Britain. The Landport Gate is behind the magazines. It has a gatehouse, called the Dead House, above the path leading into the fort. The soldiers' barracks would have been opposite the officers' quarters, but they were destroyed after the war. Only the foundations remain. The south-west bastion also has a covered magazine. West of the Water Gate is the fort's guardhouse and chapel. This building is from the late 1600s and is one of the oldest surviving places of worship inside a British artillery fort.

Images for kids

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |