Treaty of Guînes facts for kids

| Type | Treaty of perpetual peace |

|---|---|

| Context | Hundred Years' War |

| Drafted | March 1353 – April 1354 |

| Signed | 6 April 1354 |

| Location | Guînes, France |

| Effective | Not ratified |

| Mediators |

|

| Negotiators |

|

| Original signatories |

|

| Parties |

The Treaty of Guînes was a plan to end the Hundred Years' War between England and France. It was signed in Guînes, France, on April 6, 1354. This long war began in 1337. It got worse in 1340 when the English king, Edward III, said he should be the King of France.

France faced many defeats during the war. Their army lost badly at the Battle of Crécy. The important French town of Calais was also captured by the English. Both countries were tired and low on money. So, they agreed to a temporary stop to the fighting, called a truce. This truce was renewed many times, even though both sides often broke it.

In 1352, English soldiers took control of Guînes, a town important for its location. This caused the war to start again in full force. France struggled, running out of money and desire to fight. Their government also had problems. A new pope, Innocent VI, encouraged peace talks. Negotiations for a lasting peace began in Guînes in March 1353. These first talks failed, but another truce was agreed upon. Again, it was not fully followed.

In early 1354, some French leaders who wanted peace with England gained power. Talks started again. English messengers suggested that King Edward would give up his claim to the French throne. In return, England would get French land. This idea was quickly accepted, and a draft treaty was signed on April 6.

The treaty needed to be officially approved by both countries. Pope Innocent was supposed to announce it in October at his palace in Avignon. But by then, the French king, John II, had new advisors. They were completely against the treaty. King John decided that more fighting might help him get a better deal. The draft treaty was angrily rejected, and the war started again in June 1355.

In 1356, the French army was defeated at the Battle of Poitiers, and King John was captured. In 1360, both sides agreed to the Treaty of Brétigny. This treaty was very similar to the Treaty of Guînes, but it gave slightly less land to the English. The war flared up again in 1369. The Hundred Years' War finally ended in 1453, 99 years after the Treaty of Guînes was signed.

Contents

Why the War Started

Since 1153, the English kings had controlled a large area in southwest France called the Duchy of Aquitaine. By the 1330s, this land had shrunk to just Gascony. France and England often argued about who truly owned these lands. On May 24, 1337, the French king, Philip VI, declared that the English king had lost his right to these lands. This event marked the beginning of the Hundred Years' War, which lasted for 116 years.

In 1340, the English king, Edward III, claimed he should be the King of France. He was the closest male relative to the previous French king, Charles IV. This claim allowed his allies, who were also loyal to the French king, to legally fight against France. Edward was not always set on being King of France. He was often willing to give up this claim if he could keep the lands in southwest France that had historically belonged to England.

In 1346, Edward led his army across northern France. They attacked and looted the town of Caen in Normandy. Then, they badly defeated the French army at the Battle of Crécy. After that, they began a siege of the port of Calais. France was low on money and morale after Crécy. King Philip could not help Calais, and the hungry defenders surrendered on August 3, 1347.

Both sides were financially exhausted. Pope Clement VI sent messengers to arrange a truce. On September 28, the Truce of Calais was agreed upon, stopping the main fighting for a while. This agreement greatly favored the English, letting them keep all the land they had captured. The truce was supposed to end in nine months, on July 7, 1348. However, it was extended many times over the years. Even with the truce, there were still small naval battles and minor fights in Gascony and Brittany. In August 1350, John II became King of France after his father, Philip, died.

In January 1352, a group of English soldiers took the French town of Guînes by surprise. They climbed the walls at midnight. The French soldiers in Guînes were not ready for an attack, and the English took over the entire castle. The French were very angry. Their messengers quickly went to London to protest strongly to King Edward.

Edward was in a tough spot. The English had been building small forts around Calais to protect their land there. But the defenses at Guînes were much stronger. Keeping Guînes would greatly improve the safety of the English area around Calais. However, keeping it would clearly break the truce. Edward would lose honor and might start a full war, which he was not ready for. So, he ordered the English soldiers to give Guînes back.

By chance, the English Parliament was set to meet on January 17. Some of the King's advisors gave strong speeches, urging war. Parliament agreed to approve war taxes for three years. Feeling he had enough money, Edward changed his mind. By the end of January, the English commander in Calais had new orders: to take control of Guînes for the King. The soldiers who captured the town were rewarded. Determined to fight back, the French took desperate steps to raise money and gather an army. This unexpected capture of Guînes led to the war starting again.

The Fight for Guînes

When the fighting restarted, battles broke out in Brittany and the Saintonge area of southwest France. But the main French effort was focused on Guînes. The French gathered an army of 4,500 men. This included 1,500 men-at-arms (knights and soldiers) and many Italian crossbowmen. This force was led by Geoffrey of Charny, a respected French knight and the keeper of the Oriflamme, the French royal battle flag.

By May 1352, the 115 English soldiers in Guînes, led by Thomas Hogshaw, were under siege. The French took back the town, but it was hard for them to get close to the castle. This was because of the marshy land and the strong outer defenses of the castle.

By the end of May, the English had gathered over 6,000 soldiers. These troops were gradually sent to Calais. From there, they attacked the French in what historian Jonathan Sumption called "savage and continual fighting" throughout June and early July. In mid-July, a large group of soldiers arrived from England. With help from the Calais army, they managed to sneak up on the French camp. They launched a night attack, killing many French soldiers and destroying a large part of their camp's wooden fence. Soon after, Charny gave up the siege, leaving only a small group of soldiers to hold the town.

In August, the French army in Brittany was defeated by a smaller English force at the Battle of Mauron. They lost many soldiers, especially their leaders and knights. In southwest France, there was scattered fighting in the Agenais, Périgord, and Quercy regions. The English were winning these fights. French morale in the area was low, and they felt they could not drive off the English.

The Treaty of Guînes

Peace Talks

The war was going badly for the French on all fronts. They were running out of money and the will to fight. Historian Jonathan Sumption said the French government was "falling apart in jealous arguments and blame." The new pope, Innocent VI, who was related to King John, encouraged talks for a lasting peace treaty.

Discussions began in Guînes in early March 1353. They were overseen by Cardinal Guy of Boulogne. The English sent important representatives, including Henry of Lancaster, a trusted military leader. They also sent Michael Northburgh, the King's secretary, and William Bateman, the most experienced diplomat in England. The French side included Pierre de La Forêt, the Archbishop of Rouen and King John's top advisor. Also present were Charles of Spain, a close friend of John, and Robert de Lorris, John's Chamberlain.

Both sides were not fully prepared for the talks. Only two of the French group had ever negotiated with the English before. After several meetings, they agreed to pause and get more instructions from their kings. They planned to meet again on May 19. Until then, fighting would stop with a formal truce. This temporary agreement was signed on March 10.

In early May 1353, the English asked for the talks to be delayed until June. This would give them more time to discuss things. The French responded on May 8 by canceling the truce. They also announced a call to arms for all able-bodied men in Normandy. The negotiators met briefly in Paris on July 26. They extended the truce until November, but everyone knew that much fighting would continue.

The French central and local governments were collapsing. French nobles started fighting old feuds instead of fighting the English. Charles of Navarre, a powerful figure in France, broke into Charles of Spain's room and killed him. Navarre then bragged about it and tried to make an alliance with the English. Navarre and King John officially made peace in March 1354. A new balance was found within the French government. This new group was more in favor of peace with England, almost at any cost.

Informal talks started again in Guînes in mid-March. The main idea was agreed upon: Edward would give up his claim to the French throne in exchange for French territory. Edward agreed to this on March 30. Formal negotiations began again in early April. The French were represented by Forêt, Lorris, and Bertrand again, along with other important figures. The English representatives are not fully known. Discussions were quickly finished. A formal truce for a year was agreed upon, as was the general plan for a lasting peace. On April 6, 1354, these main points were formally signed by representatives from both countries, with Cardinal Guy of Boulogne as a witness.

What the Treaty Said

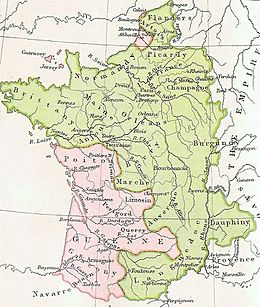

The treaty was very good for the English. England would gain all of Aquitaine, Poitou, Maine, Anjou, Touraine, and Limousin. This was most of western France. They would also get Ponthieu and the English area around Calais. All these lands would be fully English territory. They would not be held as a fief (land given by a lord in exchange for loyalty) from the French king, as English lands in France had been before.

The treaty was also meant to be a friendship agreement between the two nations. France's alliance with Scotland (which Edward claimed control over) and England's alliance with Flanders (which was technically part of France) were both to be ended. The truce was to be announced right away. However, the fact that a peace treaty had been agreed upon was to be kept secret until October 1. On that date, Pope Innocent would announce it at his palace in Avignon.

During the same ceremony, English representatives would officially give up the English claim to King John's throne. The French would officially give up their power over the agreed-upon provinces. Edward was thrilled. The English Parliament approved the treaty without even seeing the full details. The English group for the ceremony left more than four months before they were due in Avignon. King John also approved the treaty, but some of his advisors were not as happy about it.

Why the Treaty Failed

The English followed the truce. However, John of Armagnac, the French commander in the southwest, ignored his orders to keep the peace. His attacks were not very effective. We don't know exactly how much the French leaders knew about the treaty or their discussions about it. But most felt it was a bad deal. In August, it was revealed that some of the men who negotiated and signed the treaty were involved in the plot to kill Charles of Spain. At least three of King John's closest advisors either ran away or were kicked out of his court. By early September, the French court had turned against the treaty. The date for the official ceremony in Avignon was put on hold.

In November 1354, King John seized all of Navarre's lands, attacking any places that did not surrender. Planned talks in Avignon to finalize the treaty details did not happen because French ambassadors did not show up. The English messengers, who were supposed to officially announce the agreement, arrived with much fanfare in late December.

Meanwhile, King John had decided that another round of fighting might put him in a better position to negotiate. The French planned a series of big attacks for the 1355 fighting season. The French ambassadors arrived in Avignon in mid-January. They rejected the previous agreement and tried to start new negotiations. The English and Cardinal of Boulogne pushed them to stick to the existing treaty. This disagreement continued for a month. At the same time, the English group secretly planned an alliance with Navarre against France. By the end of February, everyone realized their official missions were pointless. The groups left with much anger. Their only success was a formal extension of the truce, which was not well-observed, until June 24. It was clear that from then on, both sides would be committed to full-scale war.

What Happened Next

The war started again in 1355. Both Edward and his son, Edward the Black Prince, fought in separate campaigns in France. In 1356, the French royal army was defeated by a smaller English and Gascon force at the Battle of Poitiers. King John was captured during this battle.

In 1360, the fighting stopped temporarily with the Treaty of Brétigny. This treaty was very similar to the Treaty of Guînes, but it gave slightly less generous terms to the English. Through this treaty, large areas of France were given to England, including Guînes and its surrounding county, which became part of the English area around Calais. In 1369, large-scale fighting broke out again. The Hundred Years' War did not finally end until 1453, which was 99 years after the Treaty of Guînes was signed.

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |