Charles II of Navarre facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Charles II the Bad |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| King of Navarre | |

| Reign | 6 October 1349 – 1387 |

| Coronation | 27 June 1350 Cathedral of Pamplona |

| Predecessor | Joan II |

| Successor | Charles III |

| Regents |

See list

|

| Born | 10 October 1332 Évreux |

| Died | 1 January 1387 (aged 54) Pamplona |

| Burial | Pamplona Cathedral |

| Spouse | |

| Issue more... |

|

| House | Évreux |

| Father | Philip III of Navarre |

| Mother | Joan II of Navarre |

Charles II (born October 10, 1332 – died January 1, 1387), often called Charles the Bad, was the King of Navarre from 1349 to 1387. He was also the Count of Évreux from 1343 to 1387.

Besides his kingdom of Navarre, located in the Pyrenees mountains, Charles owned many lands in Normandy, France. He inherited these from his parents, Count Philip of Évreux and Queen Joan II of Navarre. His mother had received these lands as payment for giving up her claims to the French throne in 1328. This meant Charles had important areas like Évreux and Mortain in Northern France.

Charles was a key figure during the Hundred Years' War between France and England. He often changed sides to help himself gain more power and land. He died in 1387 in an unusual accident.

Life of Charles II

Early Years

Charles was born in Évreux, France. His father was Philip of Évreux, a cousin of King Philip VI of France. His mother, Joan II of Navarre, was the only child of King Louis X. Charles often said he was "born of the fleur de lys on both sides," meaning he had royal French blood from both parents. However, his French lands were smaller than he might have hoped for. Charles grew up in France and became king at age 17. He likely did not speak the local language of Navarre when he was crowned.

In October 1349, Charles's mother passed away. To become king, he visited Navarre in the summer of 1350 for his coronation. For the first time, the oath was taken in Navarro-Aragonese, a local language, instead of Latin or Occitan. For the first 12 years of his rule, Charles spent most of his time in France. He saw Navarre mainly as a source of soldiers to help him become a powerful ruler in France. He hoped to become King of France, believing he had a strong claim through his mother. However, he could not take the throne from his Valois cousins, who had a stronger claim by male family lines.

Trouble with King John II

In 1351, Charles II served as a royal leader in Languedoc, France. In 1352, he led an army that captured Port-Sainte-Marie. That same year, he married Joan of Valois, the daughter of King John II of France. Charles soon became jealous of Charles de La Cerda, a French official who was given lands Charles felt belonged to his mother.

After a public argument in Paris in December 1353, Charles was involved in the killing of Charles de la Cerda in January 1354. His brother, Philip, Count of Longueville, led the attackers. Charles did not hide his role in the killing. Within days, he began talking with the English about military support against his father-in-law, King John II. King John II was preparing to attack Charles's lands. However, Charles's talks with King Edward III of England led John to make peace with Charles. This was done through the Treaty of Mantes in February 1354. By this treaty, Charles gained more lands and seemed to be friends with John II again. The English, who had been ready to invade France with Charles, felt tricked. Charles had used the threat of an English alliance to get what he wanted from the French king.

Relations between Charles and John II quickly worsened again. John invaded Charles's lands in Normandy in late 1354. Charles continued to plot with English leaders. Once more, Charles changed sides. The threat of a new English invasion forced John II to make another agreement with Charles, the Treaty of Valognes, in September 1355.

This agreement also did not last. Charles became friends with the Dauphin (the French prince) and seemed to be influencing him. Charles was also involved in a failed plan in December 1355 to replace John II with the Dauphin. John tried to fix things by making his son, the Dauphin, Duke of Normandy. But Charles of Navarre kept advising the Dauphin on how to rule that area.

Rumors continued about Charles's plots against the king. On April 5, 1356, John II and his supporters suddenly entered the Dauphin's castle at Rouen. They arrested Charles of Navarre and put him in prison. Four of Charles's main supporters were executed. Charles was moved from prison to prison for safety.

Charles Against the Dauphin

Charles remained in prison after John II was defeated and captured by the English at the Battle of Poitiers. Many of Charles's supporters were active in the Estates General, a kind of parliament. They tried to govern France while the king was imprisoned and the country was in chaos. They kept pushing the Dauphin to release Charles. Meanwhile, Charles's brother Philip of Navarre joined the English army and fought against the Dauphin's forces in Normandy. Finally, on November 9, 1357, Charles was freed from his prison by a group of 30 men. He was welcomed as a hero in Amiens and invited to Paris by the Estates General. He entered Paris with many followers and was "received like a newly-crowned monarch."

On November 30, Charles spoke to the people, listing his complaints against those who had imprisoned him. Étienne Marcel, a leader in Paris, demanded "justice for the King of Navarre." The Dauphin could not resist. Charles demanded payment for all damage to his lands while he was imprisoned. He also asked for a full pardon for all his actions and those of his supporters. He wanted an honorable burial for his friends who were executed by John II. He even demanded the Dauphin's own Duchy of Normandy and the County of Champagne. This would have made him the real ruler of northern France.

The Dauphin had little power. He and Charles were still negotiating when they heard that Edward III and John II were making a peace deal. Knowing this would be bad for him, Charles had all the prisons in Paris opened to create chaos. He then left Paris to gather his strength in Normandy. While he was away, the Dauphin tried to build his own army. Charles held a grand state funeral for his executed followers in Rouen Cathedral on January 10, 1358. He then effectively declared civil war, leading a combined English and Navarrese force against the Dauphin's garrisons.

Charles, the Paris Revolution, and the Jacquerie

Meanwhile, Paris was in the middle of a revolution. On February 22, the Dauphin's main military officers were killed by a mob led by Etienne Marcel. Marcel made the Dauphin a prisoner and invited Charles of Navarre to return to the city. Charles did so on February 26 with many armed followers. The Dauphin was forced to agree to many of Charles's demands for land. He also promised to pay for a standing army of 1,000 men for Charles's personal use. However, Charles became ill and could not escort the Dauphin to meetings. This allowed the Dauphin to escape his Parisian and Navarrese guards. He then started a campaign from the east against Charles and revolutionary Paris.

Etienne Marcel begged Charles to talk to the Dauphin, but nothing was achieved. The land around Paris began to be looted by both Charles's forces and the Dauphin's. In late May, a peasant uprising called the Jacquerie broke out north of Paris. This was a sudden outburst of hatred for the nobles who had brought France to such a low point. Etienne Marcel publicly supported the Jacquerie. Unable to get help from the Dauphin, the knights of northern France asked Charles of Navarre to lead them against the peasants.

Even though he was allied with the Parisians, Charles did not like the peasants. He felt Marcel had made a big mistake. He could not resist the chance to appear as a leader of the French nobles. He led the effort to put down the Jacquerie at the Battle of Mello on June 10, 1358. After the battle, many rebels were killed. He then returned to Paris and openly tried to take power, urging the people to elect him as "Captain of Paris."

This move made Charles lose the support of many nobles who had helped him against the Jacquerie. They began to leave him for the Dauphin. Charles, meanwhile, hired soldiers, mostly English mercenaries, to "defend" Paris. However, his men, stationed outside the city, raided and looted far and wide. Realizing the Dauphin's forces were much stronger, Charles began talks with the Dauphin. The Dauphin offered him a lot of money and land if he could get the Parisians to surrender. But the Parisians did not trust this deal between princes and refused the terms. Charles agreed to keep fighting as their captain but demanded that his troops stay in the city.

Soon, there were anti-English riots in the city. Charles, with Etienne Marcel, was forced by the mob to lead them against the raiding soldiers north and west of the city. These were his own men. He led them (likely on purpose) into an English trap near the bridge of Saint-Cloud. About 600 Parisians were killed.

Charles Gives Up

After this disaster, Charles stayed outside Paris at the Abbey of St Denis. He left the city to its fate as the revolution ended, Etienne Marcel was killed, and the Dauphin regained control of Paris. Meanwhile, Charles began talks with the English King. He suggested that Edward III and he should divide France between them. If Edward invaded France and helped him defeat the Dauphin, Charles would recognize Edward as King of France. He would also promise loyalty to Edward for the lands of Normandy, Picardy, Champagne, and Brie. But the English king no longer trusted Charles. Both he and the captured John II saw Charles as a problem for peace. On March 24, 1359, Edward and John made a new treaty in London. John would be released back to France after paying a huge ransom. He would also give Edward III large parts of French territory, including all of Charles of Navarre's French lands. Unless Charles submitted and accepted suitable payment elsewhere, the Kings of England and France would jointly make war on him. However, the Estates General refused to accept the treaty, urging the Dauphin to continue the war. At this, Edward III became impatient and decided to invade France himself. Charles of Navarre's military position in Northern France had worsened due to attacks from the Dauphin's forces. With news of Edward's coming invasion, Charles decided he had to make a deal with the Dauphin. After long discussions, the two leaders met near Pontoise on August 19, 1359. On the second day, Charles of Navarre publicly gave up all his demands for land and money. He said he wanted nothing more than what he had at the start of the fighting. He also said he "wanted nothing more than to do his duty to his country." It is not clear if he was acting out of patriotism because of the English invasion, or if he decided to wait for a better time to restart his campaign. After Edward's campaign in the winter of 1359–60 failed (the Dauphin avoided battle and used a "scorched earth" tactic, while the English faced terrible weather), a final peace treaty was agreed between Edward III and John II at Brétigny. John II also made a separate peace with Charles of Navarre at Calais. Charles was forgiven for his actions against France and got back all his rights and properties. Three hundred of his followers received a royal pardon. In return, he promised loyalty to the French crown again. He also promised to help clear the French provinces of the roaming groups of English and Navarrese soldiers, many of whom he had helped release in the first place.

Losing French Lands

In 1361, after his cousin Duke Philip I of Burgundy died, Charles claimed the Duchy of Burgundy. He was the grandson of Margaret, the oldest daughter of Duke Robert II of Burgundy. However, King John II took the duchy. John was the son of Joan, the second daughter of Duke Robert II. John claimed the duchy because he was a closer relative by blood. He also arranged for it to go to his favorite son, Philip the Bold, after his death.

Becoming Duke of Burgundy would have given Charles the important position in French politics he always wanted. Losing this claim made him very bitter. After failing to get Pope Innocent VI to support his claim, Charles returned to Navarre in November 1361. He soon began plotting again to gain power in France. A planned uprising of his supporters in Normandy in May 1362 failed badly. But in 1363, he made a big plan to form two armies in 1364. One would go by sea to Normandy. The other, led by his brother Louis, would join forces with soldiers in Central France and invade Burgundy. This would threaten the French King from two sides. In January 1364, Charles met Edward, the Black Prince, to arrange for his troops to pass through the English-held duchy of Aquitaine. The Prince agreed, perhaps because of his friendship with Charles's new military adviser, Jean III de Grailly, captal de Buch. This adviser was to lead Charles's army to Normandy. In March 1364, the Captal marched towards Normandy to secure Charles's lands.

John II of France had returned to London to talk with Edward III. The defense of France was again in the hands of the Dauphin. There was already a royal army in Normandy. In early April 1364, this force captured many of Charles's remaining strongholds before the Captal de Buch could reach Normandy. When he arrived, he gathered his forces around Évreux, which still held out for Charles. He then led his army against the royal forces. On May 16, 1364, he was defeated by Bertrand du Guesclin at the Battle of Cocherel. John II had died in England in April. News of the victory reached the Dauphin on May 18. The next day, he was crowned Charles V of France. He immediately confirmed his brother Philip as Duke of Burgundy.

Even with this big defeat, Charles of Navarre kept going with his plan. In August 1364, his men began to fight back in Normandy. A small Navarrese army sailed from Bayonne to Cherbourg. Meanwhile, Charles's brother Louis of Navarre led an army across France. They avoided the French royal forces and arrived in Normandy on September 23. Hearing that the civil war in Brittany had ended, Louis gave up his plan to invade Burgundy. Instead, he began to take back the Cotentin region for Charles. Meanwhile, other mercenary captains captured the town of Anse on the Burgundian border. But they only used it for raiding and looting. They did not help Charles of Navarre's cause. Pope Urban V even excommunicated one of them. Although Charles offered large sums to another leader to take command of his forces, he finally realized he could not win against the King of France. He had to make a deal with him. In May 1365, in Pamplona, he agreed to a treaty. This treaty included a general pardon for his supporters. The remains of Navarrese people executed for treason were to be returned to their families. Prisoners would be released without ransom. Charles was allowed to keep the lands he had won in 1364, except for the fortress of Meulan, which was to be destroyed. As payment, Charles received Montpellier in France. His claim to Burgundy was to be decided by the Pope. The Pope never actually made a decision. This was a disappointing end to Charles's 15 years of trying to create a large territory for himself in France. From then on, he mostly lived in his kingdom.

At the end of 1365, a mercenary named Séguin de Badefol arrived in Navarre to claim the large sums Charles had promised him for his services in Burgundy. Charles was not happy to see him. He met him in private, and it is believed that Séguin de Badefol died mysteriously after this meeting.

Charles and the Spanish Wars

When the war in France stopped, many French, English, and Navarrese soldiers became mercenaries. Many of them soon got involved in the wars in Castile and Aragon, which bordered Navarre. Charles tried to use this situation to his advantage. He made agreements with both sides that would enlarge his territory while keeping Navarre safe. Officially, he was an ally of Peter of Castile. But in late 1365, he made a secret deal with Peter IV of Aragon. He allowed an army led by Bertrand du Guesclin to invade Castile through southern Navarre. Their goal was to remove Peter I from power and replace him with his half-brother Henry of Trastámara. Charles then broke his promises to both sides. He tried to keep the Navarrese borders closed, but he could not. Instead, he paid the invaders a large sum to keep their looting to a minimum.

After Henry of Trastámara successfully took the throne of Castile, Peter I fled to the court of the Black Prince in Aquitaine. The Black Prince began to plan Peter's return to power by sending an army across the Pyrenees. In July 1366, Charles himself went to Bordeaux to talk with Peter I and the Prince. He agreed to keep the mountain passes of Navarre open for the army. For this, he would receive the Castilian provinces of Guipúzcoa and Álava, as well as more fortresses and a large cash payment. Then, in December, he met Henry of Trastámara on the Navarrese border. He promised instead to keep the passes closed, in return for the border town of Logroño and more money. Hearing of this, the Black Prince ordered an invasion of Navarre from northern Castile to force Charles to keep the original agreement. Charles quickly gave in. He claimed he had never been serious in his dealings with Henry. He opened the passes to the Prince's army. Charles went with them, but he did not want to take part in the fighting himself. He arranged for a fake ambush where he was "captured" and held until the fight for Castile was over. This trick was obvious and made Charles look foolish in Western Europe.

When the war between France and England started again in 1369, Charles saw new chances to increase his power in France. He left Navarre and met Duke John V of Brittany. They agreed to help each other if either was attacked by France. From Cherbourg, the main town in his remaining lands in Northern Normandy, he sent messengers to King Charles V of France and King Edward III of England. He offered to help the French King if he would give back his former lands in Normandy, recognize his claim to Burgundy, and give him the promised lordship of Montpellier. To the English King, he offered an alliance against France. Edward III could use Charles's lands in Normandy as a base to attack the French. As before, Charles did not really want an English army on his lands. He wanted the threat of one to pressure Charles V. But Charles V refused his demands completely. Based on Charles of Navarre's offers, Edward III sent an army to France in July 1370. He invited Charles to come to England, which he did that same month. Charles of Navarre had secret talks with Edward III, but he did not commit to much. At the same time, he kept talking with Charles V, who feared the King of Navarre would join the English army. Although Edward III signed a draft treaty with Navarre in December 1370, it became useless after the English army was defeated a few days later. In March 1371, seeing no other choice, Charles of Navarre met with Charles V and promised loyalty to him.

Having gained little from these actions, he returned to Navarre in early 1372. He was later involved in at least two attempts to harm Charles V and encouraged other plots against the French King. He then began talks with John of Gaunt, who wanted to become King of Castile. But in 1373, Henry of Trastámara, now firmly King of Castile, forced Charles of Navarre to agree to a marriage alliance. Charles also had to give up disputed border fortresses and close his borders to any army of John of Gaunt. Nevertheless, in March 1374, Charles met John of Gaunt and agreed to let him use Navarre as a base for invading Castile. Gaunt's sudden decision a few days later to give up his plans and return to England felt like a personal betrayal to Charles. To calm the Castilian King, Charles now agreed for his oldest son, the future Charles III of Navarre, to marry Henry of Trastámara's daughter Leonora in May 1375.

In 1377, he suggested to the English that he would return to Normandy. He would put the harbors and castles he still controlled there at their disposal for a joint attack on France. He also suggested that his daughter marry the new English king, the young Richard II. But the threat of an attack by Castile forced Charles to stay in Navarre. Instead, he sent his oldest son to Normandy with officials. They were to prepare his castles to receive the English. He also sent a servant whose mission was to get into the royal kitchens in Paris and harm the King of France. Meanwhile, he urgently asked the English to send him more soldiers from Gascony to help him fight the Castilians. But in March 1378, all his plots finally fell apart. On their way to Normandy, the Navarrese group was arrested. The draft treaties and letters with the English found in their bags, along with confessions from his officials, were all Charles V needed. He sent an army into northern Normandy to capture all the King of Navarre's remaining lands there (April–June 1378). Only Cherbourg held out. Charles of Navarre begged the English to send him more soldiers there, but instead, they seized it for themselves and guarded it against the French. Charles's son submitted to the French King and became a supporter of the Duke of Burgundy, fighting in the French armies. Charles's officials in France were executed.

From June to July 1378, the armies of Castile invaded Navarre and destroyed the country. Charles II retreated across the Pyrenees mountains. In October, he went to Bordeaux to ask for military help. A small English force was sent to Navarre, but they achieved little. In February, Henry of Trastámara announced his son would invade Navarre again in the spring. Having no other choices or allies, Charles II asked for a truce. By the Treaty of Briones on March 31, 1379, he agreed to Henry's demands. He agreed to be a permanent military ally with Castile and France against the English. He also had to give up 20 fortresses in southern Navarre, including the city of Tudela, to Castilian soldiers.

Charles of Navarre's tricky political career was over. He kept his crown and his country, but he was effectively a humiliated ruler controlled by his enemies. He had lost his French lands, and his kingdom in the Pyrenees was ruined and poor from war. Although he continued to scheme and still thought of himself as the rightful King of France, he was mostly powerless for the rest of his life until his unusual death.

Marriage and Children

He married Joan of France (1343–1373), who was the daughter of King John II of France. Charles and Joan had the following children:

- Marie (born 1360, died after 1400), married Alfonso II, Duke of Gandia in 1393.

- Charles III of Navarre (1361–1425)

- Bonne (born 1364, died after 1389)

- Pedro, Count of Mortain (born about March 31, 1366, died about July 29, 1412), married Catherine of Alençon in 1411.

- Philip (born 1368), died young.

- Joanna of Navarre (1370–1437), married first John IV, Duke of Brittany, and second Henry IV of England.

- Blanche (1372–1385)

Death

Charles died in Pamplona at the age of 54. It is said that he died in an unusual accident. He was very ill and his doctor had ordered him to be wrapped in linen cloths soaked in alcohol. One night, a servant accidentally set the cloths on fire, causing Charles to be badly burned. He passed away from these injuries.

Family tree

Images for kids

-

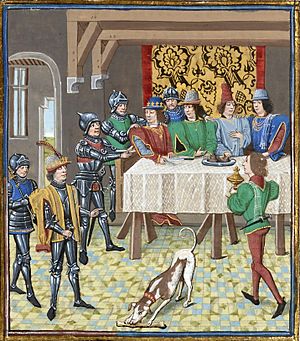

John the Good, King of France, ordering the arrest of Charles the Bad, King of Navarre; from the Chroniques of Jean Froissart.

See also

In Spanish: Carlos II de Navarra para niños

In Spanish: Carlos II de Navarra para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |