Trophic level facts for kids

The trophic level of an organism is like its spot in a food web. Think of a food web as a big map showing who eats whom in nature. A food chain is a simpler path: one organism eats another, and then it might get eaten by something else. An organism's trophic level tells us how many steps it is from the very start of this chain.

Food webs begin at trophic level 1 with primary producers, like plants. Then come herbivores (plant-eaters) at level 2. After that, carnivores (meat-eaters) are at level 3 or higher. The chain often ends with apex predators, which are at levels 4 or 5. These paths can be simple lines or complex "webs." Places with lots of different living things (high biodiversity) usually have more complex food webs.

The word trophic comes from an old Greek word, trophē, which means food or nourishment.

Contents

Who Eats What? Understanding Trophic Levels

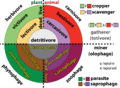

Living things get their food in three main ways: as producers, consumers, or decomposers.

- Producers (autotrophs): These are usually plants or algae. Producers don't eat other organisms. Instead, they take nutrients from the soil or water and make their own food. They use a process called photosynthesis, which uses energy from the sun. That's why they're called primary producers. Sunlight usually powers the start of almost all food chains. A cool exception is in deep-sea areas with hydrothermal vents. There's no sunlight there, so producers make food using a process called chemosynthesis.

- Consumers (heterotrophs): These species can't make their own food, so they have to eat other organisms.

- Animals that eat primary producers (like plants) are called herbivores.

- Animals that eat other animals are called carnivores.

- Animals that eat both plants and animals are called omnivores.

- Decomposers (detritivores): These organisms break down dead plants, animals, and waste. They release energy and nutrients back into the environment. This recycling helps new plants grow. Decomposers, like bacteria and fungi (mushrooms), eat waste and dead stuff. They turn it into simple chemicals that plants can use again as food.

We can use numbers to show trophic levels, starting with plants at level 1. Each step up the food chain gets the next number:

- Level 1: Plants and algae. They make their own food, so they are the producers.

- Level 2: Herbivores. They eat plants, so they are primary consumers.

- Level 3: Carnivores that eat herbivores. They are secondary consumers.

- Level 4: Carnivores that eat other carnivores. They are tertiary consumers.

- Apex predators: These are at the very top of their food web. Healthy adult apex predators usually have no other predators (except maybe other animals of their own kind).

-

Second trophic level

Rabbits eat plants at the first trophic level, so they are primary consumers. -

Third trophic level

Foxes eat rabbits at the second trophic level, so they are secondary consumers. -

Decomposers

The fungi on this tree feed on dead matter, turning it back into nutrients that primary producers can use.

In real ecosystems, most organisms are part of more than one food chain. This is because they often eat different kinds of food or are eaten by different predators. A diagram that shows all these connected food chains is called a food web. Decomposers are often not shown on food webs, but if they are, they mark the end of a food chain. Since decomposers recycle nutrients for producers to use again, some people see them as having their own trophic level.

An animal's trophic level can change if it eats different things. For example, many worms are around level 2.1, insects 2.2, jellyfish 3.0, and birds 3.6. A study in 2013 estimated that the average trophic level for humans is 2.21, similar to pigs or anchovies. But this is just an average. What people eat can be very different. For example, a traditional Inuit person who mostly eats seals would have a trophic level close to 5!

Energy Flow in Food Chains

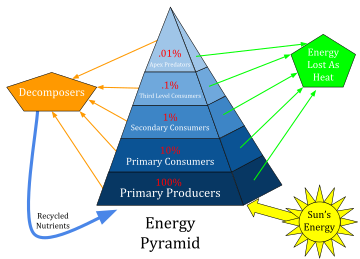

Each trophic level gets energy from the level below it. Think of it like a pyramid: the bottom level is the widest and has the most energy. This is called an energy pyramid. It shows how much energy moves from one feeding level to the next. The energy transferred can also be seen as biomass (the total weight of living things). So, energy pyramids can also be like biomass pyramids, showing how much living material is created at higher levels from what's eaten at lower levels.

The way energy or biomass moves from one trophic level to the next is called ecological efficiency. On average, consumers only turn about 10% of the energy from their food into their own body tissue. This is known as the ten percent law. Because so much energy is lost at each step, food chains usually don't have more than 5 or 6 levels. At the very bottom, plants turn about 1% of the sunlight they get into chemical energy. This means that a top consumer (like a tertiary consumer) only gets about 0.001% of the original sunlight energy.

Complex Food Webs: Fractional Trophic Levels

Food webs are very important for understanding ecosystems. Trophic levels help us see where organisms fit in these webs. But these levels aren't always simple whole numbers. This is because organisms often eat from more than one trophic level. For instance, some carnivores also eat plants. A large carnivore might eat both smaller carnivores and herbivores. For example, a bobcat eats rabbits, but a mountain lion eats both bobcats and rabbits! Animals can even eat each other, like a bullfrog eating crayfish, and crayfish eating young bullfrogs. Also, what a young animal eats, and its trophic level, can change as it grows up.

A scientist named Daniel Pauly set up a way to calculate these "fractional" trophic levels. He said plants and dead matter are at level 1. Herbivores and detritivores (which eat dead stuff) are at level 2. Secondary consumers are at level 3, and so on.

For any consumer, its trophic level is 1 plus the average of the trophic levels of all the different foods it eats.

In ocean ecosystems, most fish and other sea creatures have a trophic level between 2.0 and 5.0. A level of 5.0 is rare, even for large fish. But it can happen with top marine predators like polar bears and orcas.

Scientists can also figure out trophic levels by studying the chemicals in animal tissues, like muscle, skin, or hair. This is because a certain type of nitrogen chemical increases in a regular way at each trophic level.

Mean Trophic Level in Fisheries

In fishing, scientists calculate the average trophic level of all the fish caught in an area each year. Fish at higher trophic levels often cost more money. This can lead to overfishing of these higher-level fish. This process is sometimes called "fishing down the food web."

However, some newer studies suggest that the average trophic levels in catches haven't actually gone down everywhere. But Pauly and other scientists did notice that in the northwest Atlantic, trophic levels peaked in 1970 and then declined. They saw a shift from catching long-lived, meat-eating fish like cod to catching shorter-lived, plant-eating invertebrates (like shrimp) and small fish (like herring). This change happens because the more desired, high-level fish become harder to find. They believe this is part of a bigger problem of fisheries collapsing around the world.

Humans have an average trophic level of about 2.21, which is similar to a pig or an anchovy.

How Organisms Interact: Tritrophic Interactions

Sometimes, scientists simplify their studies by looking at only two trophic levels. But this can be tricky! There are often "tritrophic interactions" that involve three levels, like a plant, an herbivore eating the plant, and a predator eating the herbivore.

Important things can happen between the first level (the plant) and the third level (the predator) that affect how many herbivores there are. For example, small changes in a plant's genes can make it more resistant to herbivores. This might happen because the plant's shape makes it easier for the herbivore's enemies to find them. Plants can also create defenses against herbivores, like special chemicals.

Images for kids

-

The plants in this image, and the algae and phytoplankton in the lake, are primary producers. They make their own food using energy from the sun.

See also

In Spanish: Nivel trófico para niños

In Spanish: Nivel trófico para niños

- Cascade effect

- Energy flow (ecology)

- Marine trophic level

- Mesopredator release hypothesis

- Trophic cascade

- Trophic state index – applied to lakes

- Trophic dynamics – Food web

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |