USS Maine Mast Memorial facts for kids

Quick facts for kids USS Maine Mast Memorial |

|

|---|---|

| United States | |

USS Maine Mast Memorial in 2008

|

|

| For the dead of the USS Maine (ACR-1) | |

| Unveiled | May 30, 1915 |

| Location | 38°52′35″N 77°04′29″W / 38.876505°N 77.074735°W near |

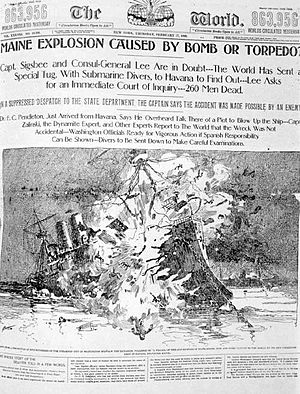

The USS Maine Mast Memorial is a special monument. It honors the people who died on the USS Maine (ACR-1). This ship was destroyed by a mysterious explosion on February 15, 1898. The Maine was anchored in Havana Harbor when it sank.

The memorial is located in Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington County, Virginia, in the United States. It features the main mast (tall pole) of the battleship. This mast sits on top of a round concrete burial vault. The vault looks like a battleship's gun turret. Sometimes, important people's remains have been temporarily placed here. These include Lord Lothian and Ignacy Jan Paderewski.

Contents

What Happened to the USS Maine?

The USS Maine was a modern battleship. The United States Navy built it to update its fleet. The ship was launched in 1889 and started service in 1895. It spent most of its time with the North Atlantic Squadron.

On January 25, 1898, the Maine sailed to Havana, Cuba. Its mission was to protect American citizens. This was during the Cuban War of Independence. At 9:40 p.m. on February 15, an explosion rocked the ship. The blast destroyed and sank the Maine.

More than 5 tons of gunpowder exploded. This instantly wrecked about 100 feet of the ship's front (bow). The middle part of the ship was badly damaged. The back part (stern) stayed mostly in one piece. The burning Maine sank very quickly. Most of the crew were sleeping in the front of the ship. They were not officers. Eight more people later died from their injuries. The ship's captain, Charles Dwight Sigsbee, and most officers survived.

It is hard to know the exact number of crew and dead. Different sources give different numbers. Most sources say 354 crew members were on board. The number of dead also varies. Some say 252, others say 260, or even more. This is because some crew members died later from their injuries.

On March 19, a U.S. Navy team investigated the disaster. They concluded that the Maine was destroyed by its own ammunition exploding. But they could not figure out what caused the explosion. Still, many people and newspapers believed Spain had used a naval mine. This led to the Spanish–American War. Later investigations have suggested other causes. These include a fire in the ship's coal storage area.

Finding and Burying the Dead in Cuba

The days after the Maine disaster were very busy. Parts of the ship stuck out of the water. The Spanish Navy and Cuban government quickly secured the area. Divers, mostly Cubans, helped bring bodies to the surface. Some parts of the ship were found far from the wreck.

Newspapers often reported wrong information about the dead. For example, they said certain bodies were found when they were not. They also got names wrong.

Finding bodies was slow. Spanish law required quick burials to prevent disease. On February 17, Havana held a funeral for 19 bodies. Thousands of people watched the procession. The Spanish military carried 19 coffins to Colon Cemetery, Havana. Another 135 bodies were found on February 19. Some were just body parts. Two more injured crew members died that day.

More bodies were found in the following days. Divers found 20 bodies trapped under a hatch on February 23. But only three could be removed right away. By March 4, 161 bodies were buried at Colon Cemetery. Recovery efforts stopped on April 3, 1898. U.S. officials thought about 75 bodies were still missing.

Burying the Dead in Key West

Some bodies found later in Havana were sent to Key West, Florida. They were buried there. The first burials happened on March 1 at City Cemetery. Captain Bowman H. McCalla organized the funeral. Marines provided an honor guard. Guns from ships fired after the service. More bodies arrived and were buried in March.

The number of bodies buried in Key West is also unclear. Some sources say 19, others 22, 24, 25, 26, or 27.

Bringing the Maine Dead to Arlington

In October 1899, a law was passed to bring the bodies from Colon Cemetery to the U.S. Representative Charles A. Boutelle wanted them reburied at Arlington National Cemetery. The Spanish–American War was over, so Spanish law no longer prevented this.

On November 27, President William McKinley ordered the USS Texas to Havana. The ship would bring the dead home. The bodies would then travel by train to Rosslyn, Virginia. From there, an honor guard would take them to Arlington National Cemetery. The Texas arrived in Havana on December 17.

U.S. Navy personnel began digging up the bodies on December 17, 1899. There was little ceremony. Each grave held one to 20 coffins. The bodies had been packed in lime to help them decompose. The remains were moved to new, tin-lined coffins. These were packed with lime and charcoal.

Mistakes in the original burial records became clear. Many numbers on the coffins were unreadable. So, identified remains became unidentified. Also, grave numbers were not always noted correctly. This made it hard to know where specific identified remains were. Some coffins still had readable numbers. The old coffins were burned.

The 151 coffins were taken to the Texas. They were placed on the ship's back deck and covered with flags and wreaths. Marines guarded them day and night.

The Texas arrived in Hampton Roads, Virginia, on December 25, 1899. The coffins were moved to funeral barges. Then, they were loaded onto a special train. Father John P. Chidwick, the Maine chaplain, traveled with the bodies. The train arrived in Rosslyn, Virginia, on December 27. The remains were then taken to Arlington National Cemetery.

A grassy hill in Arlington National Cemetery was chosen for the reburial. It was near where soldiers from the Siege of Santiago were buried. The 151 coffins held the remains of 166 people. Some families asked for their loved ones' bodies back. But the War Department decided not to allow this. All identified remains received a headstone with a name. Others were marked "Unknown."

Each coffin was draped with an American flag and had a wreath of leaves. They were placed next to open graves. Many important people attended the funeral. These included President McKinley, his Cabinet, and Admiral George Dewey.

Protestant and Catholic funeral services were held. Sailors fired a 21-gun salute. The Marine Corps Band played a funeral song. Taps were played by a bugler. Over 25,000 people watched the burial. Crowds laid flowers on the coffins. The coffins were buried in the evening.

One crewman, Frederick C. Holzer, died days after the explosion. His family was promised his body. His body was given to his family and buried in Indianapolis, Indiana.

The First Maine Memorial

Many people wanted to create a national memorial for the Maine. But early efforts did not succeed. In March 1900, Key West dedicated a statue and memorial. It was placed in the "Maine plot" in City Cemetery.

The first memorial in Arlington was built in 1900. It had a concrete base. Two Spanish mortars (cannons) captured by Admiral George Dewey were placed on brick pillars.

In the middle of the concrete base was a large anchor. This 2-ton anchor was made specially for the site. It had a wooden crossbar with a brass tablet. The tablet read:

Blown Up February Fifteenth, 1898.

Here Lie the Remains of One-Hundred Sixty-three Men of

'The Maine's' Crew Brought From Havana, Cuba.

Reinterred at Arlington, December Twenty-eight, 1899.

This memorial was similar to another one for the Santiago campaign dead.

Raising the Maine and Finding More Remains

The Maine lay at the bottom of Havana Harbor for many years. It was a danger to ships. Some people also wanted it removed to prove what caused the explosion.

Trying to Raise the Ship

In 1900, the Military Governor of Cuba, Leonard Wood, asked for the wreck to be removed. Several plans were proposed, but none worked out. One company offered to remove it for free if they could sell the relics. But they never started the work.

In 1902, Senator William E. Mason suggested raising the ship to find out why it sank. But his bill didn't have enough money. Senator Henry Cabot Lodge proposed a bill for $1 million, but it also failed.

Spain wanted the wreck removed too. In 1903, they offered to do it. But Cuba said no. Cuba then tried to remove it themselves. But the U.S. government said it still owned the Maine. So, Cuba's effort was canceled.

New Push for a Memorial

After these failed attempts, a new idea came up. The Boston Seaman's Friend Society suggested getting the ship's main mast. They wanted to put it up as a memorial in Arlington National Cemetery.

In 1908, on the tenth anniversary of the disaster, Representative Charles August Sulzer proposed raising the Maine. He also wanted any remaining dead to be buried. No action was taken on this bill.

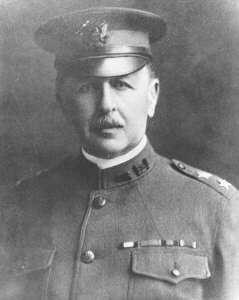

In January 1909, the Governor of Cuba, Charles E. Magoon, again asked for the Maine to be removed. The next day, Maine survivors formed the Maine Memorial Association. They wanted to hold annual ceremonies and build a larger memorial at Arlington. Admiral Charles D. Sigsbee became their president.

Law to Create the Memorial

Representative Sulzer pushed for the salvage bill again in February 1909. The bill passed the House Appropriations Committee. But the 60th Congress ended without passing it.

In 1910, Representative George A. Loud introduced the bill again. President William Howard Taft supported it. Admiral Sigsbee also called for all bodies to be brought home. He wanted a larger memorial built. Veterans groups joined in supporting this plan.

On February 28, the House Naval Affairs Committee approved the Loud bill. It said the Army Corps of Engineers should salvage the Maine. Any bodies found would be buried at Arlington. A new memorial with the Maine's mast would be built there. The House passed the bill on March 23. The Senate agreed on May 4.

On May 9, 1910, President Taft signed the "Raising of battleship Maine" bill into law. It gave $100,000 to the United States Army Corps of Engineers to remove the wreck. It also said any bodies found must go to Arlington. The Maine's mast would be taken to Arlington. It would be placed on a monument near where the dead were buried.

Getting Ready to Raise the Maine

The Army Corps of Engineers started planning in July 1910. Colonel William Murray Black led a special team. The President of Cuba, José Miguel Gómez, promised to help.

The Corps told Congress that $100,000 was not enough. On June 17, Congress added $200,000 more. The Corps decided not to bring the Maine back to the U.S. Instead, they would sink it at sea. They would build caissons (large watertight boxes) around the wreck. Then, they would pump out the water to remove bodies.

The team visited the wreck on September 10, 1910. They measured the site. The Maine was in 25 feet of water. They believed 75 bodies were still inside. The first human remains were found on September 22, 1910.

It was clear the 1898 explosion caused much more damage than thought. The ship might not float at all. President Taft approved the caisson plan on October 13. He invited Cuba and Spain to send observers.

Finding More Bodies

Work on the caissons began on December 6, 1910. They finished on March 31, 1911. Twenty caissons were built. They were driven 72 feet through water and mud. Then, over 75,000 cubic feet of water were pumped out.

The first new human remains were found on January 3, 1911. They were outside the hull. On March 12, a human foot was found stuck to a turret top. The ship's anchor was raised on March 15.

After the caissons were built, they were filled with clay and rock. Wood platforms were built on top for cranes. Water was slowly drained from inside. The search for bodies was the top priority.

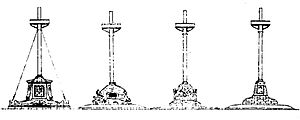

The ship's mizzenmast (rear mast) was removed and sent to the U.S. on May 27, 1911. Thirty more partial remains were found on May 3. They were mostly skulls and rib bones.

By May 31, the water was 5 feet lower. This showed that the bow (front) of the ship was completely destroyed. The middle part was also ruined. Engineers realized the hull had broken in half. They considered breaking up the wreck instead of raising it.

On June 20, more human remains were found. These included two forearms and a foot in a boot. All were charred. Workers also found many items like bayonets and binoculars.

By July 19, the water was 18 feet lower. But much of the bow wreckage was buried in 37 feet of mud. More remains were found on July 19. These were a skull and jawbone fragments. Four more bodies were found near the conning tower. These discoveries gave hope that more bodies would be found.

The ship's bell was found on July 22, 1911. It was split in half. The ship's silver service was also found.

More remains were found on July 23. These were six or seven crewmen. They were found in a jumbled, scorched mass. Some were stuck in twisted steel. The remains of three to four more men were found on July 24.

The salvage operation started running out of money. On July 26, the Corps asked for more funds. That same day, a nearly complete skeleton was found. Two more bodies were found on July 29. Congress approved more money on July 31.

On August 2, a skeleton was found in the Maine's wardroom. It was identified as Assistant Engineer Darwin R. Merritt. His body was sent home and buried in Red Oak, Iowa. Two more unidentified bodies were found. By August 14, 25 full or partial bodies had been found.

Work to remove the main mast began on September 2, 1911. This revealed more remains. Four bodies were found on September 26. Six more were found in the engine room on September 28. The last remains, a single skeleton, were found on October 16, 1911.

The Army Corps of Engineers finished its investigation in November 1911. The stern (back) of the ship was watertight. A wooden wall was built to make it float. The Corps decided to sink the ship at sea.

The Maine was sunk on March 16, 1912. About a third of the ship was wreckage. This was cut into pieces and dumped at sea. The back, left turret was given to Havana for a memorial. The front, right turret was too deep to remove. The stern was freed from the mud. Water was slowly let back into the cofferdam. The ship began floating on February 15. The USS Osceola (AT-47), a tugboat, towed the Maine out of the harbor.

Over 80,000 Cubans watched. Cannons fired as the Maine was towed out. The battleship USS North Carolina followed with the remains of the dead. Other ships also followed. About 4 miles out to sea, the ship's valves were opened. The USS Maine sank at 5:30 P.M. A bugler played taps.

After the Maine sank, the cofferdam was removed. The area was dredged to make sure nothing dangerous remained. Some heavy items were destroyed with dynamite. Operations finished on December 2, 1912.

Bringing the Last Bodies Home

Plans to receive the bodies began in June 1911. Captain James D. Tilford and undertaker Oliver B. Jenkins took charge. They were helped by Father John Chidwick. They planned to put each set of remains in a coffin.

President Gomez ordered flags to fly at half-mast in Havana. Cannons fired every 30 seconds when bodies were found.

In August 1911, President Taft ordered a battleship to carry the dead. He felt it would honor them more than a cargo ship. Major George LeRoy Irwin was assigned to oversee the bodies during transport.

On January 7, 1912, the War Department announced plans. The USS North Carolina would carry the bodies. The USS Birmingham would escort it.

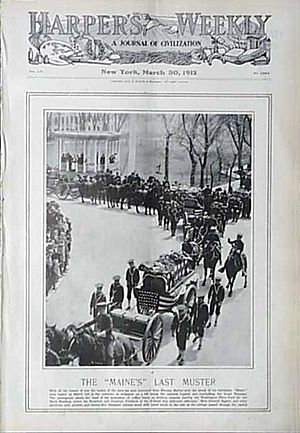

President Gomez personally oversaw the honors in Havana. There were 34 coffins. Most held the remains of two people. The coffins were moved to city hall on March 14. They lay in state overnight. Over 30,000 people paid their respects. Cannons fired every half hour on March 16.

Cuban Army artillerymen loaded the coffins onto wagons. A large group of Marines and sailors escorted the dead to the wharf. Cuban officials also joined the procession. The coffins were loaded onto funeral barges. The barges took them to the North Carolina. As the ship left the harbor, Cuban soldiers stood at attention. Funeral wreaths from the Cuban government were placed on the coffins.

Final Burial at Arlington

The USS North Carolina arrived in Hampton Roads on March 19, 1912. The bodies were transferred to the Birmingham. The Birmingham arrived at the Washington Navy Yard on March 20. The coffins were taken to the State, War, and Navy Building.

A brief memorial service was held. President Taft was the main speaker. The Cuban ambassador was also present. Father Chidwick gave a long speech.

The funeral procession then went to Arlington National Cemetery. President Taft ordered full military honors. The service was held near the Maine Memorial anchor. The Marine Corps Band played. Chaplain G. Livingston Bayard read the service. Veterans laid a white rose, evergreen, and a small American flag on the coffins. A 21-gun salute was fired. Taps were played. Over 25,000 people watched.

Estimates say between 229 and 232 dead are buried around the monument.

Building the Maine Mast Memorial

As the Maine wreck was salvaged, work on the memorial at Arlington also started. It was stopped in August 1911 due to lack of money.

The Maine's main mast was brought to the U.S. in March 1912. The foremast was also found and sent to the U.S. Naval Academy.

Work on the memorial restarted in early 1912. The United States Commission of Fine Arts (CFA) reviewed designs. They advised the War Department to pick a designer. They suggested Nathan C. Wyeth, a well-known architect. The Secretary of War agreed.

In January 1913, enough money was left from the salvage to build the memorial. President Taft wanted the memorial in the field where the Maine dead were buried. Wyeth submitted three designs. The CFA recommended one, and the Secretary of War approved it. The memorial was expected to cost $55,613.

In June 1913, the Maine's mast was moved to Arlington National Cemetery. The CFA approved a small bronze plaque for the mast.

Construction began in late November 1913. Wyeth's design included a mausoleum base that looked like a battleship gun turret. The mast went through the top. The outside was made of tan granite, and the inside was white marble. The names of those who died were carved on the outside. The granite came from Troy, New Hampshire, and the marble from Danby, Vermont. The Norcross Bros. company won the contract to build it.

Initial work went fast. Memorial services were held at the unfinished memorial on February 15, 1914. President Woodrow Wilson and Cuban President Mario García Menocal placed wreaths.

Problems with getting stone and rising costs delayed construction. By August 1914, the cost was $60,000. The memorial was not expected to be finished until November 1, 1915. However, the contractor worked faster. By January 1915, officials said it would be dedicated on Memorial Day. On February 15, President Wilson and President Menocal again placed wreaths.

Dedication of the Memorial

The Maine Mast Memorial was dedicated on May 30, 1915. This was part of Memorial Day ceremonies at Arlington. President Wilson led a march to the Civil War Unknowns Monument. Then, he gave speeches at the Old Amphitheater.

At 3:00 P.M., Marines escorted President Wilson to the Maine Mast Memorial. Father Chidwick gave an invocation. Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels spoke.

The American flag was raised to the top of the mast. Frank Arthur Daniels (age 11) and Jonathon Worth Daniels (age 13) raised the flag. They were the sons of Secretary Daniels. They also raised signal flags that spelled "Maine 1915." A 21-gun salute was fired. Marines climbed the mast's rigging. More speeches followed. Taps were played to end the ceremony.

After the official dedication, veterans groups held their own ceremony. Rear Admiral George Washington Baird spoke about the ship's history. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan also spoke.

On August 14, 1915, the Secretary of War said the memorial would be cared for by the federal government forever.

About the Memorial Today

The Maine Mast Memorial is on Sigsbee Drive in Arlington National Cemetery. It is west of the Arlington Memorial Amphitheater.

The memorial has the main mast of the USS Maine standing upright. It is in the center of a round mausoleum. The mausoleum looks like a battleship gun turret. It is 90 feet wide and 15 feet high. The mast goes through the roof and into the floor. The outside is tan granite, and the inside is white marble. The names of those who died are carved on the outside in 23 sections. There are eleven narrow windows with bronze grates. The inside roof is a shallow dome. The floor has mosaic tiles.

The entrance has two doors. The inner door is wood. Half of the ship's bell, found in 1911, is on the outside of this door. The outer door is a bronze gate with metal rope and anchors. Stone urns stand on each side of the entrance. Above the door is carved: "Erected in memory of the officers and men who lost their lives in the destruction of the U.S.S. Maine, Habana, Cuba, February 15, 1898".

A road goes around the memorial. On the east side is a concrete pad with the anchor from 1900. Two bronze Spanish mortars, captured by Admiral Dewey, are on either side of the anchor.

A bronze shield was placed on the mast by the Havana chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. It was kept when the mast was put up in 1915.

The memorial's 100th anniversary was celebrated on May 30, 2015. A wreath-laying ceremony was held. A U.S. Navy honor guard assisted. Taps were played.

Changes to the Memorial

In 1962, a stone terrace was built for the anchor and mortars. Minor repairs were made in 1917 and 1995. A partial restoration costing $500,000 happened in 2010.

In 2013, the memorial began a full restoration. The goal is to return it as much as possible to its original condition. This includes fixing damage and replacing missing parts.

Temporary Burials at the Memorial

The Maine Mast Memorial was built as a mausoleum. It has temporarily held the remains of several important people.

Lord Lothian

Philip Kerr, 11th Marquess of Lothian was the British ambassador to the U.S. He died in December 1940. His ashes were placed in the Maine Mast Memorial on December 15, 1940. This was because sea travel was dangerous during World War II.

Lord Lothian's ashes were returned to the United Kingdom in December 1945.

Ignacy Jan Paderewski

Ignacy Jan Paderewski was a famous pianist and composer. He led the Polish government in exile in London in 1940. He traveled in the U.S. to gain support for Poland. Paderewski became ill and died in New York City on June 29, 1941. His body was temporarily placed in the Maine Mast Memorial on July 5, 1941. The Polish government said his body should only return to a free Poland. President John F. Kennedy dedicated a plaque for him in May 1963.

Paderewski's remains were taken back to Poland in July 1992. This was 51 years after his death, and two years after Poland became free from communist rule.

Manuel Quezon

Manuel L. Quezon was the President of the Philippines. He was re-elected in November 1941. Just 27 days later, Japan invaded the Philippines. Quezon and his government fled to the U.S. in 1942. Quezon was very ill with tuberculosis. He died on August 1, 1944. His body was placed in the Maine Mast Memorial. It stayed there until the Philippines was free.

Quezon's body was flown back to the Philippines on June 29, 1946.

Images for kids

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |