Władysław Sikorski facts for kids

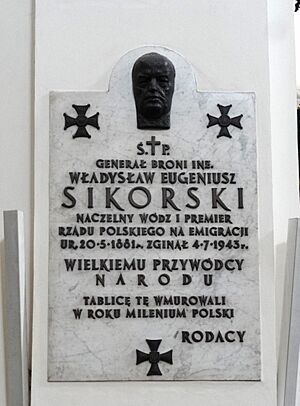

Władysław Eugeniusz Sikorski (born May 20, 1881 – died July 4, 1943) was an important Polish military and political leader. He played a key role in Poland regaining its independence after World War I. He fought bravely in the Polish Legions and later in the Polish Army during the Polish–Soviet War, where he was a hero of the Battle of Warsaw in 1920.

After these wars, Sikorski held important government jobs, including being the Prime Minister of Poland from 1922 to 1923. However, he later disagreed with another powerful Polish leader, Józef Piłsudski, and was out of political favor for some years.

When World War II began in 1939, Sikorski became the Prime Minister of the Polish Government-in-Exile. This government operated from outside Poland because the country was occupied by Germany and the Soviet Union. He also became the Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Armed Forces, leading Polish soldiers who continued to fight alongside the Allies.

Sikorski worked hard to get support for Poland from other countries, especially the United Kingdom and the United States. He also tried to improve relations with the Soviet Union, which was a difficult task. In 1943, relations broke down after the discovery of the Katyn massacre, where thousands of Polish officers were killed. Sikorski asked for an investigation, which angered the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin.

On July 4, 1943, Sikorski died in a plane crash near Gibraltar while returning from inspecting Polish troops in the Middle East. His death was a big loss for the Polish cause during the war.

Quick facts for kids

General

Władysław Sikorski

|

|

|---|---|

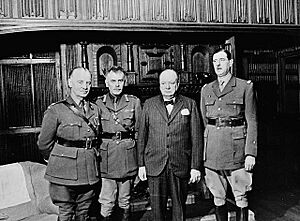

Sikorski, c. 1942

|

|

| Prime Minister of Poland | |

| In exile 30 September 1939 – 4 July 1943 |

|

| President | Władysław Raczkiewicz |

| Preceded by | Felicjan Sławoj Składkowski (in-country) |

| Succeeded by | Stanisław Mikołajczyk |

| In office 16 December 1922 – 26 May 1923 |

|

| President |

|

| Preceded by | Julian Nowak |

| Succeeded by | Wincenty Witos |

| 3rd General Inspector of the Armed Forces | |

| In office 7 November 1939 – 4 July 1943 |

|

| President | Władysław Raczkiewicz |

| Preceded by | Edward Śmigły-Rydz |

| Succeeded by | Kazimierz Sosnkowski |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Władysław Eugeniusz Sikorski

20 May 1881 Tuszów Narodowy, Austria-Hungary (now Poland) |

| Died | 4 July 1943 (aged 62) near Gibraltar |

| Cause of death | Aircraft crash |

| Political party | Independent |

| Spouse |

Helena Zubczewska

(m. 1909) |

| Children | Zofia Leśniowska |

| Profession | Soldier, statesman |

| Awards | See list below |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | Lieutenant general |

| Commands | 9th Infantry Division |

| Battles/wars |

|

Contents

Early Life and World War I

Władysław Sikorski was born on May 20, 1881, in Tuszów Narodowy, a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire that is now in Poland. He was the third child of Tomasz Sikorski, a school teacher, and Emilia Habrowska. His grandfather had fought bravely in a Polish uprising and received a special military medal.

Sikorski went to school in Rzeszów and Lwów. He studied engineering at the Lwów Polytechnic, focusing on building roads and bridges. In 1906, he joined the Austro-Hungarian army for a year and became a reserve officer. In 1909, he married Helena Zubczewska, and they had a daughter named Zofia in 1912.

Before World War I, Sikorski joined secret groups working for Polish independence. Poland was divided among three empires at the time. In 1908, he helped create the Union for Active Struggle with Józef Piłsudski. This group aimed to start an uprising against the Russian Empire. In 1910, he helped organize the Riflemen's Association, where he taught military tactics.

When World War I started in 1914, Sikorski helped organize Polish military units. He became the head of the Military Department in the Supreme National Committee. He helped recruit soldiers for the Polish Legions, an army created by Józef Piłsudski to free Poland. The Legions first fought with Austria-Hungary against Russia. Sikorski was promoted to lieutenant colonel and then colonel.

However, Sikorski and Piłsudski started to disagree. Sikorski believed in working with Austria-Hungary, while Piłsudski felt they had betrayed the Polish people. In 1917, Piłsudski was arrested, and Sikorski returned to the Austro-Hungarian Army. Later, Sikorski also protested against plans to separate Polish lands and was arrested too. Even so, their differences continued.

Poland's Eastern Wars

Fighting for Borders

In 1918, the Russian, Austro-Hungarian, and German empires collapsed. This allowed Poland to become independent again! But Poland's new borders were not clear. Conflicts quickly started with Ukrainian, Lithuanian, and Soviet forces in the east. Winston Churchill, a famous British leader, called it "The war of giants had ended, the wars of the pygmies began."

The leaders of the Soviet Union wanted to spread communism to Western Europe. They saw Poland as a bridge they needed to cross. This meant Poland's very existence was in danger.

Polish–Soviet War Hero

After being released from arrest, Sikorski helped organize the new Polish Army. He quickly returned to the front lines. He fought in the Polish–Ukrainian War, helping to defend the city of Przemyśl in 1918.

As a high-ranking officer, Sikorski led troops in the Galicia region. He commanded the Polesie Group and the Polish 9th Infantry Division. In March 1920, his forces captured Mozyr and Kalenkowicze. He also led the Polesie Group during Poland's attack on Kiev in April 1920. On April 1, 1920, he was promoted to brigade general.

As the Polish–Soviet War became more intense, the Soviet Red Army pushed back Polish forces. Sikorski successfully defended Mozyr and Kalenkowicze for a time. He also defended the Brest fortress long enough for Polish forces to retreat safely.

On August 6, 1920, Sikorski became the commander of the new Polish 5th Army. This army was tasked with defending the area north of Warsaw. He became famous for his leadership during the Battle of Warsaw, sometimes called "the Miracle at the Vistula." In this battle, Soviet forces expected an easy victory. But Sikorski stopped their advance north of Warsaw. This gave Piłsudski, the Polish commander-in-chief, time to launch a surprise counter-attack. Sikorski's forces successfully fought the Soviet 5th and 15th Armies.

After the Battle of Warsaw, Sikorski commanded the 3rd Army. His forces captured Pińsk and fought in the later stages of the Battle of Lwów and the Battle of Zamość. They then advanced towards Latvia and deep into Belarus. The Poles defeated the Soviets, and the Treaty of Riga in March 1921 gave Poland large areas of Belarus and Ukraine. Sikorski became known as one of the heroes of the Polish–Soviet War.

For his bravery, Sikorski was promoted to divisional general on February 28, 1921. He also received Poland's highest military award, the Virtuti Militari, on March 15, 1921.

In Government and Opposition

Despite their past disagreements, Piłsudski praised Sikorski and recommended him for top military positions. Sikorski was popular with many soldiers and with Polish conservatives and liberals. On April 1, 1921, Sikorski became the chief of the Polish General Staff.

Between 1922 and 1925, he held several important government jobs. He helped shape Poland's foreign policy, which aimed to keep peace in Europe and treat Germany and Russia as potential threats. He believed the military should stay out of politics.

On December 16, 1922, Poland's President Gabriel Narutowicz was assassinated. The head of the Polish parliament, Maciej Rataj, then appointed Sikorski as Prime Minister. From December 18, 1922, to May 26, 1923, Sikorski served as Prime Minister and also as Minister of Internal Affairs. He was even considered as a possible president.

During his time as Prime Minister, he became popular. He made important reforms and guided Poland's foreign policy. He helped Poland gain recognition for its eastern borders from the UK, France, and the United States in March 1923. He also supported efforts to control inflation and reform the currency. However, his government lost support in parliament and resigned in May 1923.

From 1924 to 1925, under Prime Minister Władysław Grabski, Sikorski was the Minister of Military Affairs. He worked to modernize the Polish military and strengthen the Polish-French military alliance. However, his ideas for military leadership clashed with Piłsudski's views.

From 1925 to 1928, Sikorski commanded a Military Corps District in Lwów. In May 1926, Józef Piłsudski led a military coup, taking control of the government. Sikorski, a supporter of democracy and parliament, opposed this coup. He refused to send his forces to join the struggle.

In 1928, Piłsudski removed Sikorski from his command. Although he remained in the army, he received no other assignments. During this time, he wrote books about military theory and history. His most famous book, War in the Future (1934), predicted the return of fast-moving warfare. He also wrote about Germany's growing military power.

Sikorski joined the opposition against Piłsudski's government. He spent much of his time in Paris, France, working with the French war college. Even after Piłsudski's death in 1935, Sikorski remained outside the main political and military circles in Poland. In 1936, he joined a political group called the Front Morges, which opposed the ruling party.

Prime Minister in Exile

In September 1939, Germany invaded Poland, starting World War II. Sikorski's requests for a military command were denied by the Polish commander-in-chief. Sikorski escaped through Romania to Paris. There, on September 28, he joined Władysław Raczkiewicz and Stanisław Mikołajczyk to form a Polish government-in-exile.

Two days later, on September 30, President Raczkiewicz appointed Sikorski as the first Polish Prime Minister in exile. On November 7, he also became the Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Armed Forces. Sikorski also held the position of Polish Minister of Military Affairs, giving him full control over the Polish military during the war.

During his time as Prime Minister in exile, Sikorski represented the hopes of millions of Poles. He worked to unite different Polish groups, including those who had supported or opposed Piłsudski.

His government was recognized by the Western Allies (France and the United Kingdom). However, Sikorski's government found it hard to get its voice heard. The Allies refused to call the Soviet Union an aggressor, even though the Soviets had also invaded Poland in September 1939. Sikorski also struggled to get the resources needed to rebuild the Polish Army outside Poland.

Even with Poland occupied, Polish forces continued to fight. The Polish Navy sailed to Britain. Thousands of Polish soldiers and airmen escaped from Poland through Hungary and Romania. A new Polish Army was formed in France and French-controlled Syria. A Polish Air Force was also created in France.

In 1940, the Polish Highland Brigade fought in Norway. Two Polish divisions helped defend France, and other units were being formed. The Polish Air Force in France had 86 aircraft. Even after France fell to Germany, Sikorski refused to surrender. On June 19, 1940, he met with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and promised that Polish forces would fight with the British until victory.

Sikorski and his government moved to London. They managed to evacuate many Polish troops to Britain. After signing a Polish-British Military Agreement on August 5, 1940, they built and trained the Polish Armed Forces in the West. Experienced Polish pilots took part in the Battle of Britain. The Polish 303 Fighter Squadron achieved the highest number of enemy planes shot down among all Allied squadrons. Sikorski's Polish forces became one of the most important Allied groups.

The fall of France weakened Sikorski's position. His idea of building a new Polish army in Soviet-occupied areas was criticized by some Poles in exile. On July 19, President Raczkiewicz dismissed him as Prime Minister. However, pressure from Sikorski's supporters, including the British government, led Raczkiewicz to change his mind. Sikorski was reinstated as Prime Minister on July 25.

One of Sikorski's goals was to create a federation of Central and Eastern European countries, starting with Poland and Czechoslovakia. He believed such an organization was needed for smaller states to stand up to powerful neighbors like Germany and Russia. On November 10, 1940, Sikorski and Edvard Beneš from the Czechoslovak government-in-exile signed an agreement to work together. On December 24, 1940, Sikorski was promoted to general. He visited the United States in March 1941, and again in March and December 1942.

After Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, Sikorski began talks with the Soviet ambassador in London. He wanted to re-establish diplomatic relations between Poland and the Soviet Union, which had been broken off after the Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939. In December 1941, Sikorski went to Moscow.

The Polish Government reached an agreement with the Soviet Union (the Sikorski-Maisky Pact of August 17, 1941). Joseph Stalin confirmed this agreement in December. Stalin agreed to cancel the 1939 Soviet-German agreement that divided Poland. He also agreed to release tens of thousands of Polish prisoners-of-war held in Soviet camps. Many Polish citizens were granted "amnesty," and a new army, the Polish II Corps, was formed under General Władysław Anders. This army was later moved to the Middle East. However, the location of thousands of other Polish officers remained unknown, which caused problems between Poland and the Soviet Union.

Sikorski initially supported improving relations with the Soviet Union. But he soon realized that the Soviet Union had plans for Polish territories that would be unacceptable to the Polish people. The Soviets became less concerned about their agreements with Poland after their military victories. In January 1942, a British diplomat told Sikorski that Stalin planned to move Poland's western borders into German territory, but also wanted to move Poland's eastern border much further west, taking cities like Lwów and Wilno. Sikorski was not completely against some border changes, but giving up both Lwów and Wilno was not acceptable.

Katyn and His Death

In 1943, relations between the Soviet Union and the Polish government-in-exile broke down. On April 13, the Germans announced they had found the bodies of 20,000 Polish officers in Katyn Forest. These officers had been murdered by the Soviets. Stalin claimed the Germans were responsible, but Nazi propaganda used the discovery to create a rift between Poland, the Western Allies, and the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union did not admit responsibility for this massacre until 1989.

Sikorski refused to accept the Soviet explanation. He asked the International Red Cross to investigate on April 16. In response, the Soviets accused the Polish government-in-exile of working with Nazi Germany and broke off diplomatic relations on April 25.

Starting in late May 1943, Sikorski visited Polish forces in the Middle East. He inspected the troops and tried to boost their morale. He also dealt with political issues, as there was a growing disagreement between him and General Władysław Anders. Sikorski was still open to some improvements in Polish–Soviet relations, but Anders strongly opposed this.

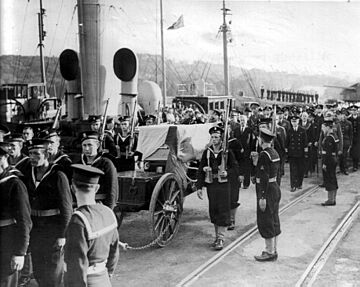

On July 4, 1943, Sikorski was returning from his inspection. His plane, a Liberator II, crashed into the sea just 16 seconds after taking off from Gibraltar Airport. Sikorski, his daughter, his chief of staff, and seven others were killed. Only the pilot survived. The crash was officially blamed on cargo shifting in the plane during takeoff.

Sikorski was buried in a Polish War Cemetery in Newark-on-Trent, England. Winston Churchill gave a speech at his funeral. On September 14, 1993, Sikorski's remains were moved to the royal crypts at Wawel Castle in Kraków, Poland.

Aftermath and Legacy

Sikorski's death was a major turning point for Polish influence among the Allies. After him, no Polish leader had as much sway with Allied politicians. His death was a severe setback for the Polish cause.

After the Soviets broke off relations with Sikorski's government, Stalin began to recall his ambassadors from Western countries. While Churchill publicly supported Sikorski's government, he privately admitted to Roosevelt that Poland would have to make concessions to the powerful Soviets. The crisis between Poland and the Soviet Union threatened the alliance between the Western Allies and the Soviets. Poland's importance to the Western Allies was decreasing as the Soviet Union and the United States joined the war.

The Allies did not want Sikorski's successor, Stanisław Mikołajczyk, to risk the alliance with the Soviets. No representative from the Polish government-in-exile was invited to the Tehran Conference (November–December 1943) or the Yalta Conference (February 1945). These were crucial meetings where the Western Allies and the Soviets decided Poland's future.

Just four months after Sikorski's death, at Tehran, Churchill and Roosevelt agreed with Stalin that all of Poland east of the Curzon Line would be given to the Soviets. This decision meant the end of the Polish government-in-exile's influence.

After the Tehran Conference, Stalin decided to create his own government for Poland. The Polish Committee of National Liberation was formed in the summer of 1944. The Soviet government recognized this committee as the only real authority in Poland. They called Mikołajczyk's government in London "illegal." Mikołajczyk resigned in November 1944, realizing his government had little power.

Stalin soon pushed for the Western Allies to recognize a Soviet-backed Polish government. By the time of the Potsdam Conference in 1945, Poland was firmly in the Soviet sphere of influence. This led to the idea of "Western betrayal" among many Poles.

Remembrance

Many poems were written about Sikorski during the war. In communist Poland after the war, Sikorski's historical role was downplayed and changed by propaganda. Those loyal to the government-in-exile faced imprisonment or even execution.

Over time, it became easier to discuss Sikorski. In 1981, on the 100th anniversary of his birth, events were held, including a conference and the unveiling of plaques. A novel about him was published in 1971, and a movie, Katastrofa w Gibraltarze, was made in 1983. The Polish government-in-exile continued until communism ended in Poland in 1990.

On September 17, 1993, a statue of Sikorski was unveiled in Rzeszów. In 1995, Sikorski became the patron of the new Polish 9th Mechanized Brigade. In 2003, the Polish parliament declared the year (the 60th anniversary of his death) to be the "Year of General Sikorski." Many streets and schools in Poland are named after him.

The memory of General Sikorski is also kept alive by organizations like the Sikorski Institute in London. In the UK, he received honorary degrees from the University of Liverpool and the University of St Andrews. In 1981, a plaque was unveiled at Hotel Rubens in London, where Polish Military Headquarters, including Sikorski's office, were located during the war. A larger-than-life statue of him was unveiled in London's Portland Place in 2000. A propeller from the plane he died in is part of a new memorial to Sikorski at Europa Point, Gibraltar.

Honours and Awards

Poland:

Poland:

Order of the White Eagle (awarded after his death in 1943)

Order of the White Eagle (awarded after his death in 1943) Commander of the Virtuti Militari (1923)

Commander of the Virtuti Militari (1923) Silver Cross of the Virtuti Militari (1921)

Silver Cross of the Virtuti Militari (1921) Grand Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta (1923)

Grand Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta (1923) Commander's Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta (1921)

Commander's Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta (1921) Order of the Cross of Grunwald, 1st class (awarded after his death in 1946)

Order of the Cross of Grunwald, 1st class (awarded after his death in 1946)Cross of Valour, four times

Gold Cross of Merit

Gold Cross of Merit Cross of Independence

Cross of Independence Cross of Merit of the Central Lithuanian Army

Cross of Merit of the Central Lithuanian Army Commemorative Medal for the War of 1918–1921

Commemorative Medal for the War of 1918–1921 Medal of the Decade of Regained Independence

Medal of the Decade of Regained Independence

- Other countries:

Military Merit Cross (Austria-Hungary)

Military Merit Cross (Austria-Hungary)Commemorative Cross of Mobilization 1912–1913 (Austria-Hungary)

Grand Officer of the Order of Leopold (Belgium)

Grand Officer of the Order of Leopold (Belgium) Order of the White Lion (Czechoslovakia)

Order of the White Lion (Czechoslovakia) Czechoslovak War Cross 1939–1945 (Czechoslovakia)

Czechoslovak War Cross 1939–1945 (Czechoslovakia) Czechoslovak War Cross 1918 (Czechoslovakia)

Czechoslovak War Cross 1918 (Czechoslovakia) Cross of Liberty for Military Leadership (Estonia)

Cross of Liberty for Military Leadership (Estonia) Cross of Liberty for Personal Courage (Estonia)

Cross of Liberty for Personal Courage (Estonia) Grand Cross of the White Rose of Finland (Finland)

Grand Cross of the White Rose of Finland (Finland) Commander of the White Rose of Finland (Finland)

Commander of the White Rose of Finland (Finland) Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour (France)

Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour (France) Commander of the Legion of Honour (France)

Commander of the Legion of Honour (France) Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Crown of Italy (Italy)

Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Crown of Italy (Italy) Order of the Rising Sun, 2nd Class, Gold and Silver Star (Japan)

Order of the Rising Sun, 2nd Class, Gold and Silver Star (Japan) Grand Officer of the Order of the Three Stars (Latvia)

Grand Officer of the Order of the Three Stars (Latvia) Grand Cross of the Order of the Aztec Eagle (Mexico)

Grand Cross of the Order of the Aztec Eagle (Mexico) War Cross with Sword (Norway)

War Cross with Sword (Norway) Grand Cross of the Order of the Star of Romania (Romania)

Grand Cross of the Order of the Star of Romania (Romania) Grand Cross of the Order of the Crown (Romania)

Grand Cross of the Order of the Crown (Romania) Commander of the Order of St. Sava (Yugoslavia)

Commander of the Order of St. Sava (Yugoslavia) Grand Cross of the Order of the White Eagle (Yugoslavia)

Grand Cross of the Order of the White Eagle (Yugoslavia)

Works by Sikorski

General Sikorski was also a writer. He wrote about military tactics and his experiences in war. Some of his works include:

- Drill Regulations of the Riflemen's Association and Basic Infantry Tactics (1911)

- At the Vistula and the Wkra Rivers: a Contribution to the Study of the Polish–Soviet War of 1920 (1923)

- Polish National Policies: Agreements and Declarations from My Tenure as Prime Minister, 18 December 1922 to 26 May 1923 (1923)

- War in the Future: Its Possibilities and Character and Associated Questions of National Defense (1934), also known as Modern Warfare: Its Character, Its Problems (1943)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Władysław Sikorski para niños

In Spanish: Władysław Sikorski para niños

- Intermarium: World War II and after

- Prometheism: Second period (1921–1923)

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |